This week, the world celebrated the International Day of Persons with Disabilities. Held on 3 December this has been marked for almost 30 years, and provides an opportunity, as highlighted by the United Nations to ‘promote the rights and well-being of persons with disabilities in all spheres of society and development, and to increase awareness of the situation of persons with disabilities in every aspect of political, social, economic and cultural life’.

Crucial to achieving this is providing access to information. As the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities states in its Article 21, governments should look to provide access to information at no extra cost.

The Marrakesh Treaty, agreed in 2013, makes achievement of this easier by removing unnecessary copyright-related barriers to the making and sharing of accessible format works for people with print disabilities. With over 100 countries now having ratified or acceded to the Treaty (or being members of the European Union, which has ratified as a bloc), there are exciting possibilities for libraries to provide more extensive services.

IFLA has been working to maintain the momentum towards not only ratification and accession, but also effective implementation of the Treaty on the ground. This is because for institutions such as libraries to be able to serve potential beneficiaries, they need the certainty that clear national laws can apply.

In this context, IFLA has called strongly on countries not to make use of the possibilities in the Treaty which can oblige libraries having already acquired copies of works to pay more for making accessible format copies, or to carry out a search of the markets before doing so. Both bring additional costs in terms of money and time which necessarily reduce resources available for service provision.

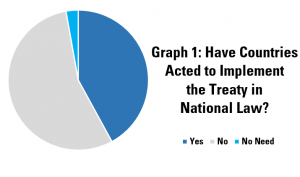

Therefore, in this week’s Library Stat of the Week, we take a look at some of the key statistics around Marrakesh implementation, based on IFLA’s Marrakesh Monitoring Report, which brings together known information from the 107 countries covered by the Treaty.

Graph 1 looks at available data on whether countries which have officially ratified or acceded have taken action to implement the Treaty in national law. To our knowledge, over 42% have done so, with a further nearly 3% not needing to, given that international laws apply directly in national law.

However, this leaves a majority which have either yet to act, or where further information is needed. Where no action has been taken – including when there are already laws in place, but these do not cover all of the issues covered under the Treaty – there is a pressing need for reform.

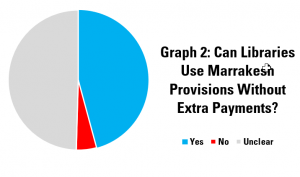

Graph 2 looks at one of the possibilities in the Treaty to restrict the scope of the new powers, notably the option to oblige libraries and others to make additional payments for making and sharing accessible format works. IFLA has argued against using this, given that it has been the failure of rightholders to make works available in accessible formats that has caused a lack of access for people with print disabilities.

This finds that, fortunately of those countries which have legal provisions in place, over 90% have not made use of the possibility to oblige such payments. This provides a powerful example for those who are still to act.

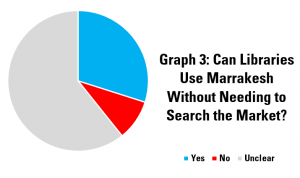

Graph 3 looks at the other possibility included under the Treaty to limit the application of its provisions by obliging libraries and others to limit their work under the Treaty to works which are not commercially available in accessible formats.

IFLA has argued that such provisions do more harm than good. If an accessible format copy is readily available on the market, libraries will seek to use this because it will be cheaper than making their own. However, obliging a check on commercial availability adds an extra bureaucratic step, and of course creates new liability – how can a library be sure, especially when sharing books across borders, or whether a book really is available or not, in the necessary format?

The graph shows that over three times as many countries which have clear provisions on the subject do not introduce restrictions here as do. Again, this provides a positive example.

It is worth noting, in both of the cases set out above, the Marrakesh Treaty makes clear that if countries wish to apply the restrictions, they need to notify WIPO. In reality, only three countries have done this (Australia, Canada and Japan). Nonetheless, Canada has not yet make use of this possibility. As such, those countries which have applied restrictions without notifying WIPO have arguably done so illegally.

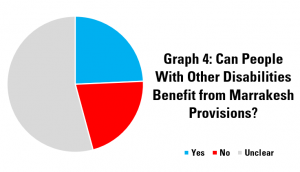

Graph 4, finally, looks at the extent to which countries have extended the possibilities to support people with print disabilities created under the Marrakesh Treaty to people with other disabilities. Despite claims by some stakeholders, this is a clear possibility for Members States.

The data indicates that, where there is clear information, more countries have indeed used this possibility than have not. This is certainly a positive step, given that the Treaty as it stands does leave out groups such as those experiencing deafness.

Overall, while there is certainly room for frustration at the slow speed of implementation of the Marrakesh Treaty into national law, among those countries that have acted, the majority have done so without introducing restrictions, and using possibilities to benefit wider groups. In doing so, they have stayed faithful to the spirit of the Treaty, as well as of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the International Day of Persons with Disabilities in general.

Find out more about library data on on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! The data supporting this analysis comes from IFLA’s Marrakesh Monitoring Report. See also IFLA’s Getting Started Guide, focused on implementing the Marrakesh Treaty.