Kelsey Corlett-Rivera, the International Language Librarian at the U.S.’s National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS) at the Library of Congress (LC), has been participating in the practical implementation of the Marrakesh Treaty in the United States since she joined NLS in July 2020. Here she shares some lessons learned as NLS finalized legal implementation, developed new workflows, and began to see positive outcomes from participation in the Marrakesh Treaty.

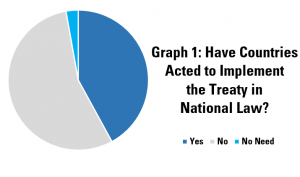

Legal Implementation Takes Time: The United States was well positioned to join the Marrakesh Treaty, given that a copyright exception for the blind and print disabled had already been signed into law in 1996 and U.S. representatives were involved in negotiations. Even then, NLS, the country’s largest accessible library, was not able to fully participate in cross-border exchanges until nearly seven years after the United States signed the Treaty on October 2, 2013.

To amend U.S. law in accordance with the Treaty, the President signed the Marrakesh Treaty Implementation Act into law in October 2018. On February 8, 2019, the U.S. deposited the instrument of ratification to the Treaty in Geneva, and the Treaty entered into force in the U.S. in May 2019.

Next, the Library of Congress Technical Corrections Act, which incorporated the terminology of the Treaty into NLS’s authorizing statute and allowed NLS to participate in the cross-border exchange of digital content was signed into law in December 2019. Finally, the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations had to be amended in accordance with the Act, which was accomplished in July 2020. That completed the legal prerequisites, but operational execution is ongoing.

Other countries with no prior copyright exceptions or other legal challenges may expect even longer timelines before full participation in the sharing of accessible content across borders.

Different Countries Have Different Approaches: Since NLS was established in 1931, we have primarily provided human-narrated audiobooks and human-transcribed braille books to eligible patrons. Our formats have evolved over time, going from records to cassettes to digital files that can be downloaded directly, even in the case of braille. This approach mirrors that of quite a few other countries, such as Canada, Australia, and many European countries. But even then, formats can differ. NLS creates digital talking books in accordance with the ANSI/NISO Z39.86-2002 Standard, as it offers additional features beyond the older DAISY 2.02 format that many other countries still use. NLS uses .brf files for our digital braille books; other countries use .bra, .brl, or several others. Different choices have been made regarding number of braille lines per page; even the varying paper sizes commonly used in different regions can lead to incompatibilities. Many less-developed countries lack the specialized software and large digital storage capacities needed for human-narrated, fully accessible audiobooks, and therefore prefer text files that are then read using text-to-speech capabilities. These differences mean that in many cases it is not simply a matter of sending files for requested books — conversion work has to be done at some point in the process in order for books obtained from abroad to function in local systems and meet local patron expectations.

Metadata Matters: A great deal of information is gathered about the books that NLS and similar libraries around the world add to our collections. While this includes typical details like title, author, and publisher, accessible books often require additional datapoints. Audiobook duration, the braille code used when the book was originally transcribed, the name of the narrator, and many other pieces of information are necessary for patrons to understand exactly what they are getting when they download a book. Even if a book shared by another country is in English and of interest to patrons in the United States, the descriptive metadata is often in another language. Neither our patrons nor our systems are prepared to decipher words like the Swedish “Talbok” (audiobook) or “Inläst med talsyntes” (synthetic speech). This means that books frequently need to be re-cataloged, which impacts the speed with which we can add new titles.

Central Leadership Is Critical: The Accessible Books Consortium (ABC), a public-private partnership led by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), has developed a central online catalog (Global Book Service) to facilitate the exchange of accessible books through the Marrakesh Treaty. They have worked tirelessly to ensure the platform functions well for both institutional and individual users, and led efforts to standardize metadata and formats to begin addressing some of the challenges faced by NLS and others. Authorized Entities (non-profit groups eligible to participate according to the Treaty) have shared nearly 900,000 books via GBS, over 40 percent of which can be downloaded immediately. NLS has orchestrated direct agreements with entities in several other countries to exchange books, but the books we have shared via GBS have been downloaded by nearly 50 different countries. The overhead required to set up agreements and arrange file-sharing mechanisms with each and every one of them would be impractical at best and impossible at worst. ABC also provides training to developing countries in producing accessible books and advocates for born-accessible publishing, thus working to lessen the global book famine in many different ways.

Marrakesh Has Made a Huge Difference! While countries have faced challenges during legal implementation, and there are many still making their way through the process, the Marrakesh Treaty really has made a huge difference for people who are blind and print disabled around the world. The Treaty is now in force in 118 countries. As mentioned, a huge number of books are now available through the ABC Global Book Service. As of June 2023, NLS has uploaded over 194,000 items to GBS, which have been downloaded more than 5,000 times in 47 countries since 2020. NLS patrons have also benefited, as we have added over 5,500 books in nearly 30 different languages to our collection. A patron in California was delighted to find audiobooks in Persian that had been obtained via Marrakesh after worrying that he might never read in his native language again after losing his sight. Another patron in Minnesota requested a Finnish translation of Tolstoy’s Resurrection, which NLS never would have been able to fulfill without being able to get a copy from Celia, our counterpart in Finland. Stories like this abound, and while many countries continue to work through the beginning stages of implementation, the effort that advocates and lawmakers have put into the Marrakesh Treaty has had, and will continue to have, a major impact.