The COVID-19 pandemic has further underlined an issue that was already painfully clear around the world – that health is too often an equalities issue.

Yet it has also made clear that without action to improve the health and wellbeing of all, we cannot overcome challenges. This is the case both in the shorter term in the form of the pandemic, and longer term in the shape of non-communicable diseases and other causes of suffering.

To respond, and so build a healthier, fairer world – the theme of World Health Day 2021 – action is needed to ensure that everyone can live healthier lives, reducing the risk of falling ill – public health.

Libraries themselves are aware, through their own experience, of how much they are used to access health information. As noted, for example, in a survey of Philadelphia librarians, each member of staff was receiving on average ten health-related queries a week, underlining that regardless of whether they are formally involved in planning, libraries are part of the health infrastructure. There are plenty of articles and presentations from the field, setting out ideas and experiences – see our own article from 2019.

This blog, however, looks at what public health professionals themselves are saying about libraries. This matters, because for our institutions to be part of plans to promote better health and wellbeing, libraries need to be recognised by the people preparing them. Therefore, all the links in this piece point to research or actions taken by actors outside of the library field.

We hope that they can help you in your advocacy.

Priorities for Public Health

In working to understand health inequalities, a key area of focus are the social determinants of health. A piece in the Journal of Community Health in 2019 set out ten of these, based on a previous study – transport, addiction, stress, food, early life, the social gradient (education), social exclusion, work, unemployment and social support.

Each of these has an impact on the likelihood of people getting ill, and then of getting treated (including preventative measures). Action can rely on efforts outside of traditional health policy – almost all of the issues set out above are not usually immediately associated with health – but their impact is significant.

A second concern is around how to reach out into communities, the focus of a whole book. Many people will go out of their way to avoid formal health institutions such as hospitals, but even health professional themselves may struggle to reach people.

As we have seen in the pandemic, a particular tragedy has been where people with COVID have not wanted to admit that they are ill or seek medical attention for fear of losing their jobs. In other situations, cultural factors may play a role, there may be distrust of officials, or simply language barriers.

Finally, there is the importance of health literacy – the ability to understand and use information concerning health (for example, from the Urban and Community Studies Institute at the University of New Brunswick). As opposed to the other two issues, which are more about the context determining health, this focuses more on the skills of individuals and communities. It represents a key goal of course, with a health literate population more able to look after themselves and cope with new threats.

Where do Libraries Fit In?

Even from a relatively superficial look at the literature, the potential of libraries is recognised through experience.

Concerning the social determinants of health, as a University of Pennsylvania study underlined, libraries’ work to build basic literacy and support lifelong learning is already a key contribution to supporting better health outcomes. Beyond this, wider programming to support employability and inclusion should also make a positive difference. There is also of course the role of libraries, alongside other institutions, in using their hiring and purchasing power to support local economies and create jobs, where this is possible.

There are also more specific interventions, such as those promoted in libraries in Norfolk, in the UK, in partnership with local public health authorities in order to encourage health eating and promoting wellbeing. Indeed, such initiatives showed the power of libraries to mobilise other local stakeholders, such as supermarkets to get involved. Similarly in Redbridge, London, UK, collaboration with sports and physical activities teams led to efforts to promote healthy cooking and eating, especially in school holidays.

Libraries also have reach into communities, often disproportionately serving more vulnerable populations. From simply being an effective place to display relevant information to the wider community (as noted by Public Heath England), they can also actively contribute insights about what people in situations of marginalisation may need, based on their experience and the questions they receive.

For example, people in rural areas or the unconnected may have few ways other than libraries of gaining access to key health information. For others, they will feel far more comfortable coming to the library than going to the doctors or a formal health centre. The nature of libraries as a public space, open to all, can be powerful. Libraries can also train (or host training for) people who can then take key information out into the community, or be a base for health professionals to work with people in a more comfortable environment.

The unique role of libraries around literacies can also make them useful partners in building health literacy. At a fundamental level, there is provision of relevant information and collections, potentially in collaboration with national public health authorities (for example in the United States or United Kingdom).

Combined with their ability to reach out to vulnerable groups, it is recognised that libraries can help overcome stigma, and even build comfort around more difficult questions such as clinical trials and preventative interventions.

Through this work, libraries can play a key role in delivering on the promise of eHealth in general, as illustrated by the Australian Digital Health Agency’s partnership with the Australian Library and Information Association.

In short, as noted in a Journal of Community Health article, libraries can be a key ‘meso’ level actor in promoting population health, working between national or regional health agencies and individuals.

What More is Needed?

As set out in the previous section, libraries are well placed to support action in key areas of focus for public health professionals – the social determinants of health, meaningful outreach, and building health literacy. As highlighted at the beginning – and indeed recognised by the Robert Wood Johnston Foundation – they are already part of the ‘community’s health enhancing environment’.

Nonetheless, more can be done. While the links in this article do lead to evidence of public health professionals and other non-LIS experts recognising the value of working with libraries, it is clear that more can be done to convince public health planners.

To a large extent, this will be down to libraries themselves being able to show how their unique characteristics can help them contribute meaningfully. This work can be helped, however, through more systematic evaluation of interventions, as well as bringing public health researchers into libraries in order to see for themselves the work that libraries do, as well as to plan activities collaboratively.

A further area of focus could be on building knowledge and skills among library professionals (also underlined in CDC work on preventing chronic disease), in order to help them better to fulfil the role that they often already have in providing advice and information to users. Clearly, access to resources also matters here.

As we look beyond the pandemic, and make plans for the healthier, fairer world highlighted for World Health Day, the potential of libraries to contribute is clear.

With wider recognition of this role in the health field, building on existing evidence, and work to improve libraries’ own ability to provide information and services, there is scope for libraries to play a much more central role in public health policy planning and delivery around the world.

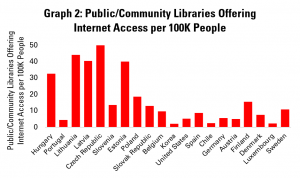

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

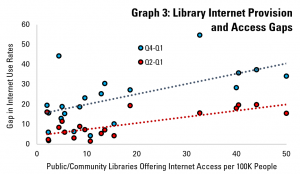

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens. We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

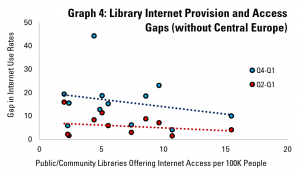

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access. As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.