Why US Courts consider public library as the “quintessential locus” of information in a free and democratic society.

By Tomas Lipinski (Professor, School of Information Studies, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee)

Anyone following recent library developments is the United States is likely to have seen legislative efforts in various states to restrict access to LGBTQIA+ or Critical Race Theory-related content.

Yet these challenges often do not have success in court. In one recent case, a Texas court ordered initially-restricted content be restored [Little v Llano County, 2023 WL 2731089 (W.D. Tex.)], and in another, a new Arkansas law regulating content in public libraries was held unconstitutional [(Fayetteville Public Library v Crawford County Arkansas, 2023 WL 4845636 (W.D. Ark.)].

Why do courts protect a patron’s access to a wide variety of content in public libraries? Such access is essential to a free and democratic population. It is so essential that many courts have concluded that it is a Liberty Interest under the U.S. Constitution which cannot be deprived unless the requirements of Due Process are satisfied under the Fifth Amendment.[i]

As the Texas court observed: “First Amendment right to access to information in libraries, a right that applies to book removal decisions … many courts have held that access to public library books is a protected liberty interest created by the First Amendment.” Little v Llano County, 2023 WL 2731089, *8 (W.D. Tex.). The case is currently on appeal; Little v Llano County (23-50224, 5th Cir., April 4, 2023). Oral arguments were heard on June 7, 2023. A decision is expected this fall.[ii]

Texas court decided to “follow[] our many sister courts in holding that there is a protected liberty interest in access to information in a public library.” Id. at *9.[iii]

The nature of the public library Liberty Interest has solemn historical origins.: “Our founding fathers understood the necessity of public libraries for a well-functioning democracy.” Fayetteville Public Library v Crawford County Arkansas, 2023 WL 4845636, *3 (W.D. Ark.). Over time, the public library emerged as the prime source of the supply of information in society – and the legal protections that support libraries endure in our changing information society. “By 1956, Congress formally acknowledged the need for all citizens to have access to free, public libraries by enacting the Library Services Act, which authorized millions of dollars in federal funds to develop and improve rural libraries and fund traveling bookmobiles to serve rural communities. Through public libraries, free access to knowledge became possible for all Americans, regardless of geography or wealth.” Id.at *4 *footnote omitted). The Texas court observed similarly: “Silencing unpopular speech is contrary to the principles on which this country was founded and stymies our collective quest for truth.” Fayetteville Public Library v Crawford County Arkansas, 2023 WL 4845636, *5 (W.D. Ark.).

The Arkansas law used an “appropriateness” standard when considering challenges to library content, vested final authority for removal (and acquisitions) not with trained library professionals but with local officials, and removed the immunity for libraries from criminal prosecution for having library materials that are obscene or harmful to minors content. A public library belongs to the people, not the government that funds it.

The court commented that: “By virtue of its mission to provide the citizenry with access to a wide array of information, viewpoints, and content, the public library is decidedly not the state’s creature; it is the people’s.” Fayetteville Public Library v Crawford County Arkansas, 2023 WL 4845636, *5 (W.D. Ark.). “The State is wrong on all fronts, starting with its treatment of Pico. The Pico case [Board of Education, Island Trees Union School District No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982)] does not stand for the proposition that there is no constitutional right to receive information.” Id. at *20. The right to receive information is best accomplished through the free public library. As best said in the seminal Kreimer v. Bureau of Police for Town of Morristown, 958 F.2d 1242, 1255 (3d Cir. 1992) case: “Our review of the Supreme Court’s decisions confirms that the First Amendment does not merely prohibit the government from enacting laws that censor information, but additionally encompasses the positive right of public access to information and ideas. Pico [Board of Education, Island Trees Union School District No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982)] signifies that, consistent with other First Amendment principles, the right to receive information is not unfettered and may give way to significant countervailing interests… this right… includes the right to some level of access to a public library, the quintessential locus of the receipt of information.”

On this day celebrating access to information, let us celebrate the critical role that our public libraries play in that achieving a free and open society.

[i] “No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militi[i]a, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

[ii] The restricted content in the Texas case were the following titles: Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent by Isabel Wilkerson; Called Themselves the K.K.K: The Birth of an American Terrorist Group by Susan Campbell Bartoletti; Spinning by Tillie Walden; In the Night Kitchen by Maurice Sendak; It’s Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex and Sexual Health by Robie Harris; My Butt is So Noisy!, I Broke My Butt!, and I Need a New Butt! by Dawn McMillan; Larry the Farting Leprechaun, Gary the Goose and His Gas on the Loose, Freddie the Farting Snowman, and Harvey the Heart Has Too Many Farts by Jane Bexley; Being Jazz: My Life as a (Transgender) Teen by Jazz Jennings; Shine by Lauren Myracle; Under the Moon: A Catwoman Tale by Lauren Myracle; Gabi, a Girl in Pieces by Isabel Quintero; and Freakboy by Kristin Elizabeth Clark.

[iii] Other courts have come to similar conclusions: “The right of the public to use the public library is best characterized as a protected liberty interest created directly by the First Amendment. Since the right is not absolute, it can be lost for engaging in conduct inconsistent with the purpose of public libraries.” Doyle v. Clark City Public Library, 2007 WL 2407051, *5 (S.D. Ohio) and Wayfield v. Town of Tisbury, 925 F. Supp. 880 (D. Mass 1996) (4-month suspension from public library without a hearing in response to a disruptive event): “this court finds that Wayfield states a sufficient claim to support a finding that the suspension of his access to the library was a deprivation of a ‘liberty or property right.’” Id. at 885.

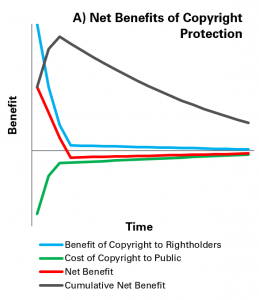

Graph A offers a way of reflecting on this, for a complete set of works published in a given year. The horizontal axis represents time after publication, and the vertical, benefits/costs. Figures are not included, as the graph provides a model, rather than a set calculation, and because it can be hard to put a clear figure on monetary costs or benefits to some things.

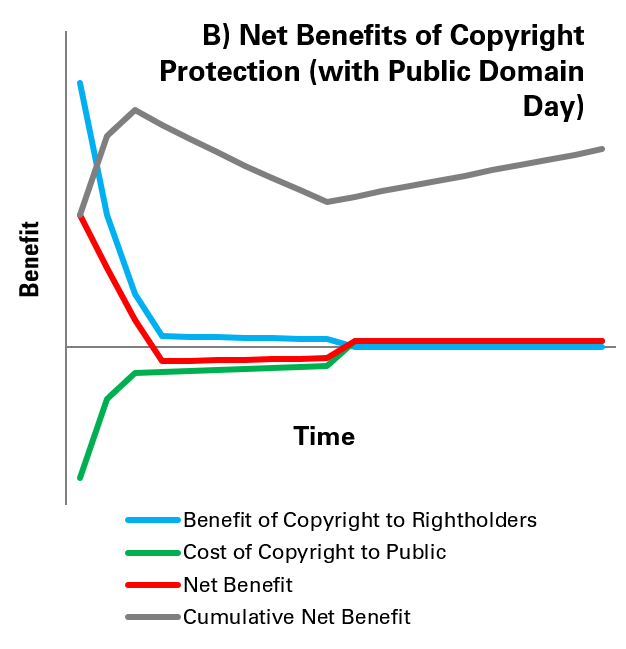

Graph A offers a way of reflecting on this, for a complete set of works published in a given year. The horizontal axis represents time after publication, and the vertical, benefits/costs. Figures are not included, as the graph provides a model, rather than a set calculation, and because it can be hard to put a clear figure on monetary costs or benefits to some things. Entry into the public domain provides a response to this situation of a falling cumulative net benefit over time. Graph B illustrates this. At halfway along the horizontal axis, works from a given year enter the public domain, and so benefits to rightholders from sales and licensing fees (blue line), which were already low and falling, are reduced to zero. However, the costs to the public (green line) also disappear, and in fact turn into benefits as people are able to use and enjoy works freely.

Entry into the public domain provides a response to this situation of a falling cumulative net benefit over time. Graph B illustrates this. At halfway along the horizontal axis, works from a given year enter the public domain, and so benefits to rightholders from sales and licensing fees (blue line), which were already low and falling, are reduced to zero. However, the costs to the public (green line) also disappear, and in fact turn into benefits as people are able to use and enjoy works freely.