Alongside the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, a core focus of the United Nations 2030 Agenda is the importance of tracking progress. The two go together; there is little point in setting objectives without establishing also a means of tracing how well countries are doing in achieving them.

In order to support this at the global level, the United Nations has established a list of 231 unique indicators. Member States are encouraged to collect and present data for these (where methodologies have been agreed), as well as finding other metrics that can help track progress towards the SDGs.

This blog sets out ways in which you can propose datasets collected for IFLA’s Library Map of the World as indicators of progress towards the SDGs.

The Limits and Possibilities of Library Map of the World Data as SDG Metrics

In each case below, it is argued that library data can be used as a proxy for something that matters, such as how much a society is investing in equality or lifelong learning, or how much people are using community spaces.

Clearly, these are just proxies. First of all, in the absence of wide-ranging household surveys, it is difficult to show specific causality between library data and specific outcomes at a national or regional level, a point also made in the EBLIDA report on SDG Indicators in European libraries.

Nonetheless, there are correlations which allow us to make certain points in our advocacy about how strong and well-used library fields tend to be associated with various positive outcomes (see our Library Stat of the Week series for more).

It should be noted, in contrast, that in the context of individual projects, it is possible to gather feedback and results from participants which can indicate what is possible, as illustrated in the SDG Stories on IFLA’s Library Map of the World.

More fundamentally, the fact that the UN is using 231 indicators underlines that measuring progress towards the SDGs relies not on any one single metric or index, but on a wide range of them. As this blog argues, library data certainly can have its place in the mix.

Number of libraries

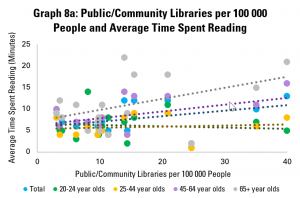

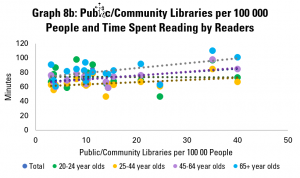

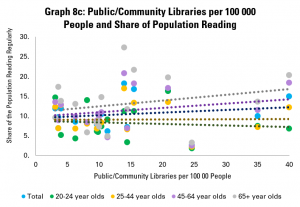

First of all, the number of public or community libraries in a country can be used as an indicator of how strong the infrastructure is for supporting literacy and lifelong learning (SDGs 4 and 8), as well as providing community space (SDG 11), a basic service for all (SDG 1), and as a place for accessing eGovernment (SDG16). With the role of culture recognised in delivering the SDGs as a whole, you can also use this data as an indicator of levels of access to culture.

You can provide figures for numbers of libraries per person in order to compare the situation in your country with those elsewhere, or calculate the average area served by each library to indicate how far people are, on average from a library.

The number of school libraries, in those countries which have not given school library responsibilities to public libraries, can be a further indicator of quality education (SDG 4). If you can find how many schools there are in your country, you can indicate what share of these do, or do not, benefit from library services. As highlighted in our analysis of Voluntary National Reviews so far, the presence (or absence) of school libraries is often seen as an indicator of the strength of the wider education system.

Numbers of academic and research libraries can serve as an indicator of the quality of the infrastructure for supporting research and innovation (SDG9), as well as for supporting success of all students (SDG4).

Finally, the existence of a national library can provide an indication of the development of institutions in general (SDG16), given the role of these libraries in supporting the wider book sector, and in ensuring the preservation of the historical record for future generations.

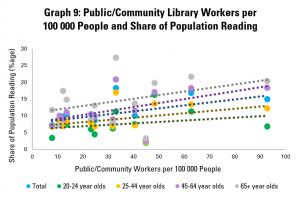

Number of library workers

Where available, numbers of library workers can be presented as providing a more accurate idea of the strength of the library field, and so of the infrastructure for supporting education and literacy (SDG4), skills development and job-seeking (SDG8), access to culture and other services (SDG1), community-building (SDG11) and research (SDG9).

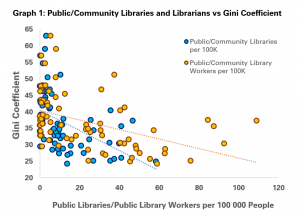

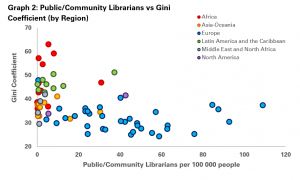

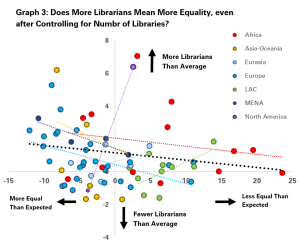

In particular, numbers of library workers correlate much more strongly than numbers of libraries with outcomes such greater equality (both between women and men, and on other dimensions such as immigrant background and wealth). As such, numbers of libraries can provide an indicator of investment in pro-equity policies (SDGs 5 and 10).

Once again, you can calculate numbers of library workers per million people or per student in order to develop a comparable idea of the strength of libraries and library services in your country. This approach also allows you to cancel out the impact of a tendency to more but less well-staffed libraries in some countries, and fewer but better-staffed libraries in others.

Libraries with internet access

The digital divide remains a reality, defined not just as the gap between those with and without internet access, but also between those who have the confidence and competence to use the internet effectively, and those who do not.

Libraries have an acknowledged role not only in bringing people online, but also in fostering the skills needed to make safe and effective use of the internet, with a strong focus on groups which might otherwise be excluded.

As such, you can propose data on the number of libraries providing internet access as an indicator of how effectively a country is providing support for everyone to make the most of the internet (SDGs 5, 9 and 17). In particular, you may want to focus on the number of libraries offering internet access per million people (as a way of allowing comparisons with other countries), and the share of libraries which are offering internet access.

Numbers of visits and registered users

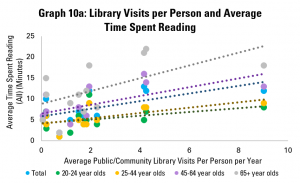

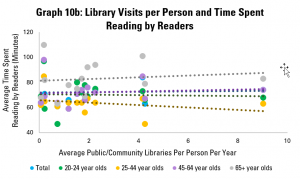

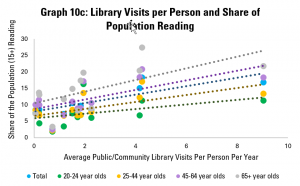

Moving from the strength of the library field to the use made of it, data about the number of visits to libraries per year, and the share of the population registered can be proposed as an indicator of the effectiveness of government policies around education, culture, research and community activities.

For example, Finland used data on library visits as a metric of engagement in learning in its 2020 Voluntary National Review (SDG4). Visits to libraries also tend to correlate with wider engagement in culture, which is relevant across the SDGs. Numbers of visits can also be used as an indicator of level of use of public spaces (SDG11).

Numbers of loans

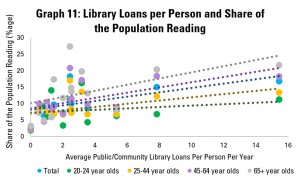

Another indicator of levels of use of libraries, at least in their core role of supporting reading and research, is the number of loans they make. You can calculate this on a per-person basis, at least if you have national-level data.

While, arguably, lending books is only one part of the work of many libraries now, it can still be used as an indicator of engagement in reading and learning (SDG4), and research (SDG9) as well as of wider cultural engagement.

Hopefully, the ideas in this blog give you can idea of how you may be able to propose library data to the authorities responsible for tracking progress towards the SDGs. Depending on what your country is already doing – and the data you have available – you will want to adapt your message of course. In particular if your country is carrying out a Voluntary National Review, there may be interesting opportunities to engage.

Let us know how you get on!