An idea that has picked up a lot of attention in the last couple of years in urban development discussions has been that of the 15-Minute City.

The concept – or similar ones – have been around for a number of years, with Carlos Moreno often cited as the primary source, but was most prominently taken up by the Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, in her successful 2020 re-election campaign. Since then, a number of global organisations – including the C40 Cities network – have taken it up with enthusiasm, and it features near the top of The City We Need Now 2.0, a recent publication of the World Urban Campaign (see a future blog).

It provides a neat way of bringing together a lot of thinking about how to make cities more liveable into a single, understandable idea – that people should be able to do all of the essential things in their lives – shopping, eating, working, relaxing, learning – within a 15-minute walk or bicycle ride.

It stands in contrast to models of cities where people need to travel much longer distances – often by private transport – in order to fulfil these basic needs, leading not only to pollution and lost time, but also a sense of dislocation.

This is particularly the case in cities subject to sprawl (i.e. which spread over huge spaces) or with unmixed zoning (i.e. residential areas are kept separate from commercial or industrial ones). Too often, for example, distant suburbs or housing estates are the ones that experience the most serious problems. Many groups in such areas, for example, may simply be unable to travel long distances, for reasons of cost, disability, or simply lack of time.

Moreno himself, in his TED talk, sets out four underlying principles: 1) ecology – the idea that we need to be promoting ways of living that are better for the environment and nature, with more green spaces and less pollution; 2) proximity – the idea that key services (including culture) are close by; 3) social connection – that people benefit from knowing their neighbours and building stronger relations and collaborations, and 4) engagement – that people need to more closely involved in decision-making about their areas.

The library angle

As highlighted, while the term ’15-minute city’ may be new, it brings together existing ideas, including many which will be familiar to libraries. Indeed, the idea of libraries providing services in places that don’t require people to drive is already familiar from the IFLA Green Library Checklist.

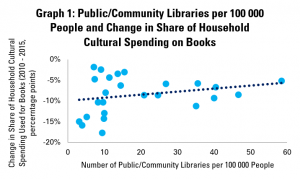

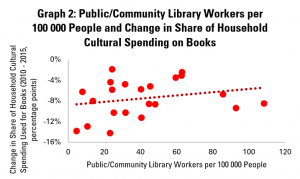

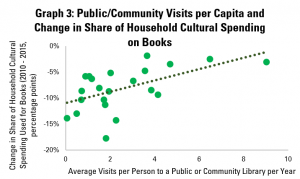

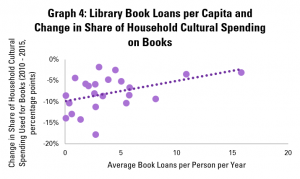

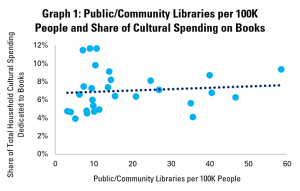

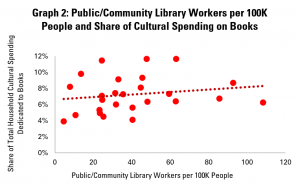

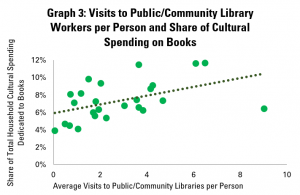

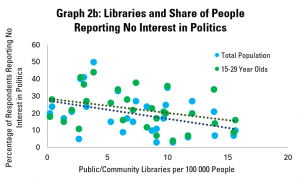

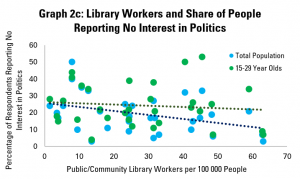

Firstly, there is the obvious role of networks of public and community libraries in providing services in proximity to their users. It is well understood that in order to respond to local needs, a key factor for success is being close enough to be able to understand these, and give everyone an opportunity to benefit. Protests against library closures often focus on the fact that forcing users to travel longer distances risk excluding them. It is a source of pride that libraries represent perhaps the densest network of cultural institutions that many cities or countries have.

A second angle is the idea of multi-functionality. 15-Minute City proponents argue that there needs to be better use of space, including flexibility to ensure that any one building or location can serve a number of purposes and publics. This is of course what libraries already do, acting as centres for culture, education, democracy, public health, and beyond. This is supported by libraries’ emphasis on responding to user needs, rather than trying to apply a rigid, one-size-fits-all service model. This is also something that libraries are developing, building on their role – often – as the only non-commercial indoor public space, with dedicated staff and internet access.

Strongly connected to the above is the emphasis on the social function of libraries as places not just for individual study or enjoyment (although this if of course important), but also for interaction. As highlighted, it is vital to have these opportunities outside of commercial locations or those that may be off-limits for different groups. Here too, libraries around the world are developing their capacity as meeting places, where social capital can be built and maintained. Through offering programming, rooms, access to shared cultural references, opening eyes to other cultures, or simply by allowing people to be together, they make the difference.

A further role of libraries, again linked to the above, is in boosting democracy. Collective decision-making of course starts with a feeling of belonging to the same community, and being able to talk, discuss, share, and work together to develop new ideas. As highlighted, libraries already enable this through their social function. However, they can go further, for example acting as centres for providing access to – and facilitating use of – local open data. They can be venues for consultations and conversations between decision-makers and citizens. And they can help fight misinformation by building the skills to evaluate and use information effectively.

Questions to address

Of course, the 15-minute city concept does raise questions, and indeed has its critiques, notably from those who suggest that without significant efforts, it tends to be richer areas and communities that benefit. For example, in Paris, the conversion of roads along the Seine in parks was seen as primarily benefitting the (better off) communities living there, at the expense of those living further away, and who rely on their cars to get to work.

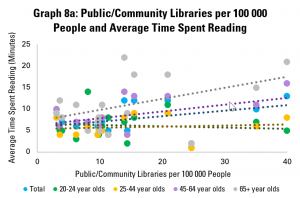

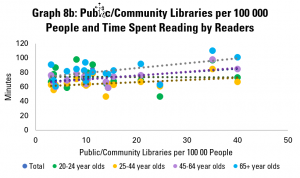

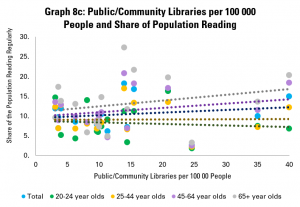

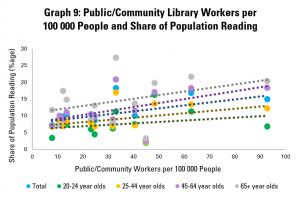

For libraries in particular, there is the question of how to manage the perceived trade off between scale and impact – is it better to have fewer, bigger institutions with more possibilities to offer services and programming, or more, smaller ones (for example, see the variation highlighted in our Library Stat of the Week post)?

Of course, this may be a false dichotomy. When working effectively as a network, smaller libraries can benefit from the advantages of scale, for example in access to collections. However, it is clearly also the case that offering a wide range of programming and activities with reduced space and staff is harder than for a big central library.

Connected to the critique of 15-minute cities mentioned above, there is a particular need to ensure that all communities – not just wealthier ones – benefit. This implies a need to invest more in library services in deprived areas.

This of course can have a major pay-off, given that it can be people facing poverty who can benefit most from library services, and who would otherwise not be able to travel longer distances to a bigger institution. However, it does of course require investment, and strong support for librarians so that they in turn can share have the greatest positive effect. This includes work within the library field to share ideas and resources, from the level of local networks of libraries, to the national and even the global level.

A powerful reference for library advocacy

The idea of a 15-Minute City has the potential to be a powerful one for libraries, given how far it plays to our institutions’ existing strengths. We can fit in well with urban development agendas that use it as a reference point, although of course may need to work to remind decision-makers that this is the case.

At the same time, it does raise questions that libraries will need to address, notably about how to ensure that all residents of towns and cities have reasonable access to libraries. Ideally, we can make the most of 15-minute city policies to ensure that our institutions – and profession – receive the investment and support needed to (continue) to make this a reality.