In a three-part series to end our regular #LibraryStatOfTheWeek posts, we are looking at data around culture, and crossing this with information gathered by IFLA through the Library Map of the World.

Last week’s post – the first of the mini-series – therefore looked at the link between the strength of library fields (including how well used they are), and the share of household spending on culture that is dedicated to books.

This is a helpful indicator, especially in a digital age where different activities are competing for our free time and resources. Given that overall tendencies to spend on culture will be determined by a variety of external factors (earnings and disposable incomes for example), this can even be a more meaningful way of understanding the place of reading – and books – in societies.

Libraries themselves have an important role in promoting reading, both in terms of helping adults discover new works, and in ensuring that coming generations turn into capable and confident readers.

This week, we look beyond the figures for one year (2015), and rather at evolutions in spending between the two years for which data is available – 2010 and 2015. This allows us to see how well spending on books, as a share of overall household cultural spending, has fared at a time that new online cultural activities were emerging.

Once again, data on household cultural spending comes from Eurostat (and so focuses only on European countres), while data on libraries and use comes from the IFLA Library Map of the World (latest available year), crossed with population data from the World Bank in order to obtain per capita figures. In each of the analyses noted below, we have only included a country when all relevant data was available.

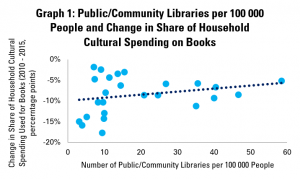

Graph 1 starts by comparing numbers of public and community libraries per 100 000 people with the change in the share of household cultural spending going on books between 2010 and 2015.

In the graph, each dot represents a country. The higher it is, the more positive the change in share of spending has been. The further to the right it is, the more libraries there are per 100 000 people.

It is worth noting that, in all countries covered by this data, the share of household cultural spending going on books has fallen. This makes sense, given the points set out above concerning the rise of online entertainment.

The graph indicates that, in general, countries with higher numbers of public and community libraries per 100 000 people have tended to see smaller falls in the share of cultural spending going on books.

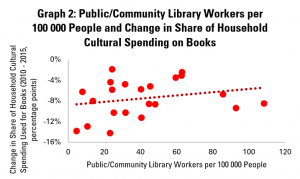

Graph 2 looks rather at numbers of public and community library workers per 100 000 people. Dots further to the right on this graph therefore indicate countries with a higher number of such workers.

Here too, the story is positive – where there are more public and community library workers, in general, falls in the share of household cultural spending going on books have been lower. In other words, book sales have resisted better to competition where libraries are stronger.

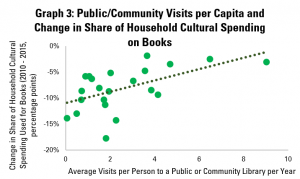

Graph 3 looks at numbers of visits per person to public and community libraries. This shows a relatively strong, positive correlation between library use and changes in the share of household cultural spending going on books.

This tallies with the finding last week that library visits, in particular, seem to be well-connected to the economic situation of the book sector. This makes sense – libraries can be important shop-windows, and of course also build enthusiasm for reading.

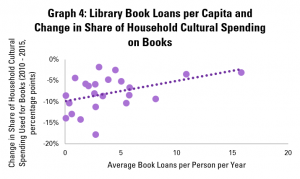

Graph 4 looks at average numbers of book loans per capita. Again, there is a positive correlation – and indeed a stronger and more positive one than in the graph last week looking at spending in just one year.

In other words, library lending tends to be associated with better performance over time for the book sector.

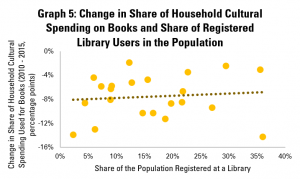

Graph 5, finally, looks at connections between numbers of registered library card holders (calculated as a share of the population), and trends in the share of books in total household cultural spending.

This again shows a positive correlation, although a less strong one, although partly driven by the result for Spain, where there is a high rate of library card holding, but also a big fall in spending on books as a share of overall cultural spending.

Overall, these figures provide further helpful support for advocacy around the value of our institutions in supporting a healthy book sector.

While correlation does not mean causality, it is possible to show that, far from greater library use being associated with lost tales, it is rather the opposite. These figures can be used in arguments to show that cuts to libraries – for example making it more difficult to visit and borrow – could be harmful to the book sector as a whole.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.