Four years ago, Education International, the world’s leading international education trade union organisation, launched its Declaration on Education Support Personnel (ESP), defined as covering a wide range of professional, administrative, technical, and general staff working within the education sector such as teaching assistants, school nurses and psychologists, bursars, bus drivers, and, of course librarians.

The day of the signing of the Declaration, 16 May, was set by the organisation as World Education Support Personnel Day, and since then, each 16 May has brought events and publications highlighting the specific needs of ESP.

With many ESP being members of wider education unions, this was a logical step, but also a reminder of the need to remember that effective education and teaching depends on a wide range of people.

IFLA and libraries have of course long underlined how essential library services are for education throughout life, with both the Public Library Manifesto and School Library Manifesto stressing our institutions’ and profession’s ability to contribute to learning.

Yet is is also true that school libraries in particular face real challenges in the face of cuts to education spending (see stories from the US about ‘disappearing’ school librarians), while university librarians can face challenges in asserting their status vis-à-vis other departments (see, most recently, stories from Texas A&M).

There is a pressing need to ensure that libraries are seen as having a central – rather than a peripheral or optional – role in education. We need it to be clear that libraries are not disposable – a nice-to-have rather than a need-to-have – and indeed are key to delivering the new vision of education set out in UNESCO’s Futures of Education report.

As part of these efforts, Education International’s Declaration on ESP is a powerful support for advocacy. This blog sets out three key arguments which libraries and library associations can then draw on in advocacy:

Librarians and other ESP are central to education: As already indicated above, the Declaration offers strong support for a vision of schools and wider learning environments that recognises how essential ESP are. They help ensure that learning environments are positive and safe, delivering on the right to education, and indeed contribute significantly to building the ‘whole student’, with the full range of skills needed to succeed.

Crucially, this means, as article 5 indicates, that ‘ESP are a part of a team of education employees that contribute to student learning. They deserve to be valued and respected for their contribution to quality education’. Importantly, and reflecting a wider Education International priority, the Declaration also comes out strongly against out-sourcing.

Librarians and other ESP must be given equal treatment and be involved in decision-making: the follow on from this point is that given their role in supporting learning, ESP should be fully engaged in the way in which schools and other institutions are run. Logically, this includes the way in which knowledge and skills are shared and developed.

Furthermore, the landing page for Education International’s work in this area underlines that for similar levels of qualification and experience, librarians and other ESP should enjoy the same rights and status as formal teaching personnel. This would certainly be welcome, underlining that librarians and others must not be treated as second-class.

Librarians and other ESP deserve decent working conditions: again following on from the above, the Declaration underlines that there is specific need to work to give ESP – and so librarians – quality employment. This is not just about salaries, but also about employment perspectives, and a freedom from threats of harassment or other insecurity.

This is indeed the focus of this year’s World Education Support Personnel Day, which stresses deteriorating conditions for many in the field, and indeed loss of status or job security.

The Declaration is therefore a useful reference for libraries and library associations around the world working to protect the status of librarians based within education institutions, both in mobilising the support of wider education unions, and in engaging directly with governments.

Take a look at the Education International website for additional insights, information and research that can help you in your advocacy.

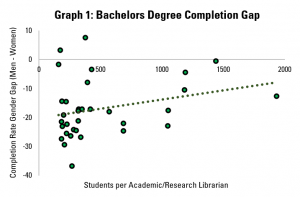

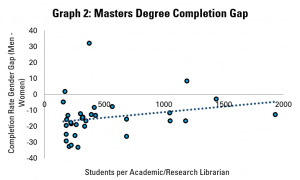

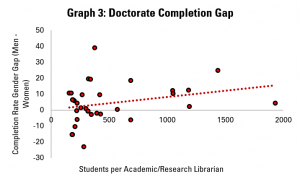

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.