In last week’s Library Stat of the Week, we looked at the relationship between the number of librarians per student and per researcher, and rates of completion of studies and publication per researcher respectively.

This week, we dig a little deeper into the first of these two questions by using gender dis-aggregated data for completion rates from the OECD.

In effect, this allows us to understand whether greater levels of academic or research librarian support for students (calculated by the number of students each librarian serves) can be associated with a more or less favourable gender gap for women.

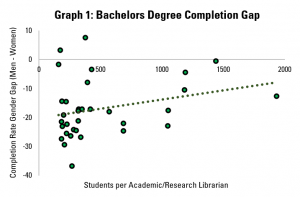

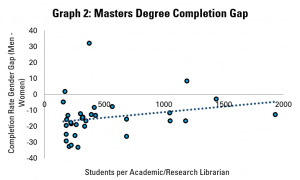

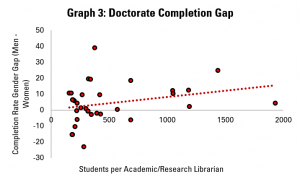

Graphs 1, 2 and 3 do this for students at bachelor’s, masters and doctoral levels respectively. In each graph, each dot represents a country for which data is available.

On the horizonal (X) axis, there is the number of students per librarian. Countries which are more to the left have fewer students per librarian (a proxy for better librarian support), while those on the right have more students (and so less librarian support).

On the vertical (Y) axis, there is the result of subtracting the completion rate for women from the completion rate for men. A figure above zero indicates that a greater share of men complete their studies than women, while a figure below zero suggests that more women finish than men.

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.

In terms of the strength of the relationship, it is relatively similar across the levels, with the closest correlation seen at doctoral level (which may make sense, given the intensity of research required for this).

Outside of library support, it is noticeable that while the gender gap tends to favour women at bachelors and masters level, more men tend to complete their doctorates than women.

As part of any gender equality strategy, efforts to ensure that more women get the qualifications needed to get into the highest skilled jobs are likely to play a key role. At the doctoral level, there is clearly work to be done. It could be worth looking further at the role that stronger libraries services can play in ensuring that women get the support needed to complete their studies at this level.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.

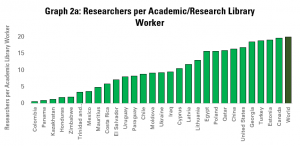

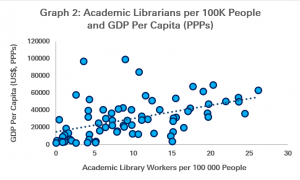

In other words, while in general, richer countries tend to have more academic library workers, this is not always the case. Some very rich countries have relatively few, while some poorer countries have relatively many.

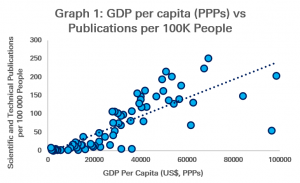

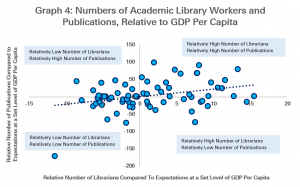

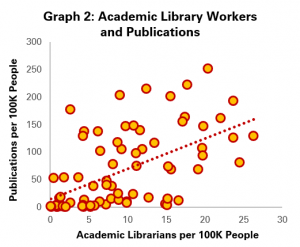

In other words, while in general, richer countries tend to have more academic library workers, this is not always the case. Some very rich countries have relatively few, while some poorer countries have relatively many. In this graph, a negative figure on the vertical axis indicates that they are producing relatively few publications for their level of GDP per person, while a positive one indicates higher publishing rates.

In this graph, a negative figure on the vertical axis indicates that they are producing relatively few publications for their level of GDP per person, while a positive one indicates higher publishing rates.

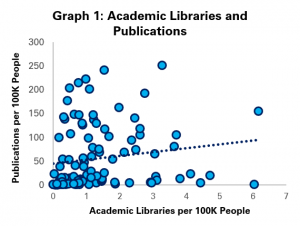

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1).

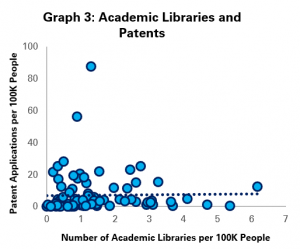

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1). Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people.

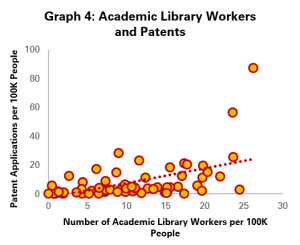

Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people. Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.