Last week the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) released the 13th edition of its Global Innovation Index (GII). This looks to bring together different indicators that can help governments and others understand how different countries are doing in promoting innovation, which is taken to be a key source of growth and progress towards wider development goals.

The index takes a wide perspective on innovation – not just specific activities such as patenting, but also evaluations of the innovation environment (institutions governing innovation, human capital, infrastructures, sources of finance and opportunities to sell innovative products, and businesses’ own behaviour), and a wider range of measures of outputs and their dissemination and use, including online.

The report as a whole – and the measures that underpin it – are worth exploring for anyone interested in how something as broad as innovation can be defined and measured. This is particularly true for the library field, given the role of our institutions in supporting and promoting basic research in particular, through their work with faculty in universities and other research centres.

It is also, clearly, a crucial moment to think about the way that innovation is encouraged and managed, given the impacts of COVID-19 on economies. The report includes various perspectives on funding, as well as insightful commentary on what the pandemic may mean more broadly.

This blog, as a starter, identifies five key points made in the GII 2020, which may be of particular relevance.

Spending on research and development is likely to fall – we will need to ensure what money is there is spent effectively: the most prominent graph in the report highlights that the first three months of 2019 have already seen a drop in spending on research and innovation, likely as companies became aware of the potential costs of the pandemic. Governments too are likely to look to reduce spending also in the coming months – and indeed, the latest proposal for the European Union’s Multi-year Financial Framework already (mistakenly, in the view of libraries) plans to do this.

Clearly, any decision to cut spending on innovation cannot be taken lightly. But where this is the case, it will be necessary to think hard about how to maximise efficiency. A clear way of doing this is through promoting openness in science, which has the potential to make research both faster and fairer. A wider analysis of the way research is shared can also help identify where money is being removed from the system unnecessarily, reducing that actually spent on creating and applying new ideas.

There is a positive trend towards international cooperation between researchers which should be encouraged: the report notes that despite the many stories of countries failing to coordinate around border controls or purchases of vaccines, the scientific community has proven itself readier to work across borders in order to share ideas, data and results. It underlines how much of a positive this is, echoing existing findings by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development that cross-border collaborations tend to lead to higher impact research.

Support for research cooperation is a key focus for many academic libraries. Clearly encouraging openness (not only of publications, but also of science in general) will help with this by reducing (or removing) copyright-related barriers to collaboration. So too will progress towards an international legal instrument on copyright limitations and exceptions at the World Intellectual Property Organization. Yet libraries are also, through work around linked data and developing and updating standards, facilitating the sharing and use of information across borders to advance innovation.

Steps to remove red-tape have been welcome and can continue to contribute to supporting innovation: another positive underlined by the report is the effort made by many governments to simplify processes around innovation. These have focused in particular on financing, as well as on some rules around testing. Clearly it will be important in the longer term to assess which of these changes should be made permanent – rules are usually there for a reason – but this will allow for a re-evaluation.

Once again, the value of simplifying rules and processes around innovation will be positive for libraries. For example, in discussions around the copyright rules that should apply to text and data mining, it is clear that research is facilitated when there is no need to seek additional permissions, or buy additional licences in order to carry out mining – the right to read should be the right to mine. Similarly, the complexity that libraries face in giving access to digital resources, each subject to their own set of contract terms, could be easily removed by simply underlining that such terms should not be enforceable when they override copyright limitations and exceptions.

Countries with more flexible copyright regimes tend to top the tables for their regions: Once again, it is countries with flexible rules around copyright – namely fair use or fair dealing – which top the tables in five out of the seven regions highlighted by WIPO. The United States in North America, India in Southern and Central Asia, Singapore in South-East and Eastern Asia and Oceania, Israel in North Africa and Western Asia, and South Africa in Sub-Saharan Africa all have such rules.

The only exceptions are in Europe (Switzerland) and Latin America and the Caribbean (Chile). Nonetheless, both have recently updated their copyright laws to favour access to information in support of innovation. This provides a helpful argument in favour of greater flexibility as a means of supporting more innovation.

Innovation will be essential for the recovery from COVID-19: an overall point – and one that could be expected from a report with this title – is that innovation is likely to be essential for any future recovery from COVID-19. This was already the case before of course, with limits on the world’s resources meaning that ‘doing better’ has to replace ‘doing more’ as a driver of growth. Faced with COVID-19, we need to innovate both in order to find ways of carrying on with lives and services, and to create new opportunities for work and earning.

As a key part of the innovation infrastructure of any country – in particular the basic research that makes major breakthroughs possible – libraries will certainly be able to agree with the importance of a focus on encouraging the development and spread of new ideas. It is only to be hoped that governments, when taking decisions about the future, will do the same.

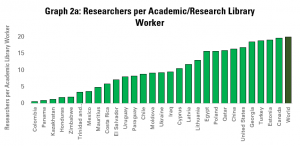

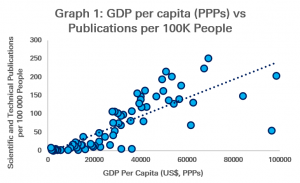

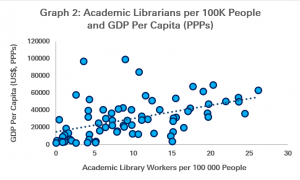

In other words, while in general, richer countries tend to have more academic library workers, this is not always the case. Some very rich countries have relatively few, while some poorer countries have relatively many.

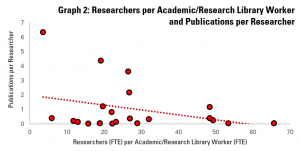

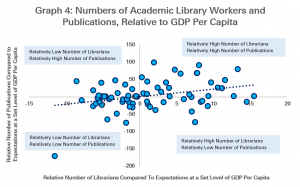

In other words, while in general, richer countries tend to have more academic library workers, this is not always the case. Some very rich countries have relatively few, while some poorer countries have relatively many. In this graph, a negative figure on the vertical axis indicates that they are producing relatively few publications for their level of GDP per person, while a positive one indicates higher publishing rates.

In this graph, a negative figure on the vertical axis indicates that they are producing relatively few publications for their level of GDP per person, while a positive one indicates higher publishing rates.

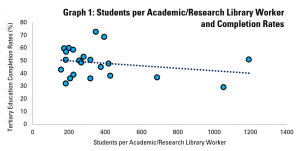

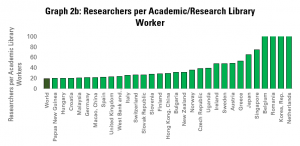

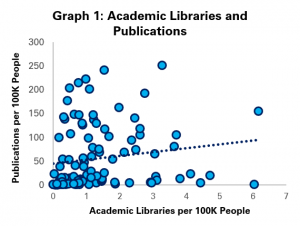

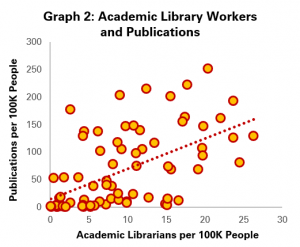

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1).

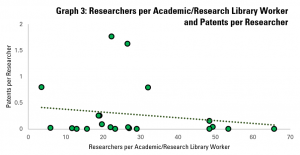

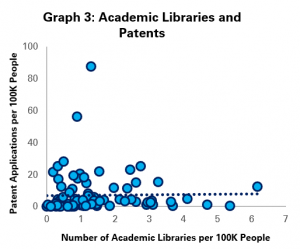

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1). Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people.

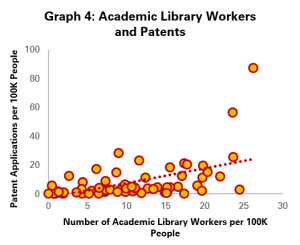

Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people. Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.