With the obligation to close their doors for the safety of users and staff alike, the ability of libraries to offer services digitally has never been so important.

Libraries have responded, diverting available resources and energies into providing online storytimes and consultations, and developing their presence on social media.

Some have sought to reassign budgets from physical to digital collections, sometimes with supplementary funding offered by public authorities. This experience is, for many, making clear the differences in what libraries’ money can buy in the offline and online worlds, especially as concerns eBooks.

This is not a new concern of course. Libraries have been highlighting concerns about the way the library eLending market has been working for years, with high prices, restrictive terms, and simple non-availability of works all regularly featuring.

While much of the attention has been on ‘trade’ eBooks – those lent out by public libraries – this is an issue that also affects academic libraries (as our interview with Johanna Anderson underlined).

In terms of solutions, the focus has tended to be on copyright, and how to update rules in order to ensure that the provisions that allow for libraries to work with physical books should apply also to electronic ones.

However, copyright – as well as exceptions to it – are a response to problems in a market, either because a public good is not being supplied, or because the structure and operation of the market is working to the disadvantage of one party or another. This, of course, is the job of competition and consumer policy.

Following on from an earlier blog on this site about how competition – or anti-trust – policy applies in the world of libraries, this one looks to explore what evidence we have – and what evidence we might need – in order to encourage competition and markets authorities to look into the way that library eBook lending operates.

To do so, it will look at a number of the steps usually taken in competition investigations in order to assess the need for an intervention.

Are there excessive profits?

A first potential indicator of problems with the market is when producers are making profits that can be considered higher than usual.

The theory at least suggests that if a market is competitive, then high profits will tend to attract more companies. This will generate more competition, which will drive profits down, for the benefit of consumers.

Looking at eBook markets, it does not seem to be the case that ‘trade’ publishers are enjoying huge profits, although the big players have seen rises in recent years, often however on the back of audiobooks.

On the academic side, major publishers do make high profit levels, although again not necessarily just on the back of their eBook operations.

However, profit levels alone are not a sure sign of a competition issue.

Is the market concentrated?

In many investigations, the next place to look in trying to work out whether a market is not working is whether there is a limited number of competitors. A large share of the market held by just one or a few companies could indicate a problem.

When it comes to eBooks, the picture is different for ‘trade’ and academic books. In the case of the former, there are plenty of publishers putting out novels and other materials.

With academic journals, there is a well-documented concentration of much of the market in the hands of a number of publishing companies, and concern every time that there is talk of a merger or take-over.

However, even were one of the big publishing companies to disappear, the market would remain to compare favourably with that for internet providers or airlines in many countries.

Of course, this is to assume that the market is for eBooks in general. Alternatively, we can look at the market for a single book. In this case, the rightholder has a monopoly thanks to copyright.

Clearly this is a violation of perfect competition, but one that – at least theoretically – can be justified in terms of giving the rightholder the time they need to recoup their investments. Whether the current length of copyright terms in international law has anything to do with economic logic is another question.

Crucially, the monopoly awarded to the rightholder of a particular eBook is easier to justify when these are substitutable – i.e. when eBook A by publisher X could broadly be replaced by eBook B by publisher Y.

When, however, this is not the case – i.e. because a student or researcher needs a very specific work, or a library card-holder wants to read the latest bestseller, not something a bit like it – there is more of a challenge.

Another solution would be to allow physical books to compete – for example by allowing a library to digitise a physical copy in their collection, and give access on a one-copy-one-user basis. However, this idea is deeply contested.

Even initiatives focusing on out-of-commerce works, such as Controlled Digital Lending, have led to threats of legal action, while the Hathi Trust’s work to provide digitised copies of books now is largely justified by the fact that access to physical copies is impossible.

Were a competition investigation to be launched, a key question would therefore be how the market is defined, and whether allowing physical books to compete with eBooks could bring a degree more competitiveness to markets for individual works without undermining the possibilities for rightholders to recoup investments.

Are there barriers to entry?

A further step in an assessment of competition is to look at whether there are issues that may be preventing competitors from entering a market, and competing with existing companies by offering cheaper alternatives.

Clearly if we are considering each individual eBook as a separate market, then there is a huge barrier to entry – copyright. But as suggested before, just like other forms of intellectual property, copyright at least originally had a form of economic logic.

But even if we look at academic eBooks as a whole, there can also be challenges. As set out in our interview with Johanna Anderson, publishers can tend to want users to access their eBooks through their platforms.

However, if libraries don’t want to – or can’t – buy access to every platform available, the only alternative is to buy individual eBooks from vendors, but often at prices which have been set many times higher than those of print equivalents. This serves to push libraries towards publisher platforms, despite the fact that the library may only want a small share of the eBooks available there.

The effect of this is, effectively, to push libraries towards buying access to bigger platforms, potentially at the expense of spending on smaller, newer publishers.

This risks creating a barrier to entry by smaller players (or forcing them out of the market) by making it more difficult for libraries to allocate money more freely between publishers on the basis of what users actually want.

This situation is similar to that already seen with the ‘big deals’ offered for bundles of journals, which a number of countries are beginning to seek to abandon, even at the risk of losing access to content that researchers and students want.

In the trade eBook sector, there can also be issues with barriers to entry, for example when libraries or library systems are obliged to buy a fixed number of books.

The same goes when it is possible to sell bestsellers under terms that mean that they ‘capture’ large share of library budgets, leaving less space for new or emerging voices. In each case, established players gain an advantage that risks creating barriers for others.

A competition investigation here could shed more light on the subject of whether specific practices of bundling, or minimum purchases, have a negative effect on new entrants or customers.

Is there market power?

A final issue to explore, linked to the question of barriers to entry, is whether a particular player enjoys market power.

This implies that one side of the equation (a producer or buyer) has a freedom to change conditions – for example by raising or lowering prices, or imposing tougher or looser terms – and the other has little option but to accept, for example because there is no alternative.

This can be a real concern for libraries faced with demand from users – from readers coming to a public library, to students or researchers at an academic one.

As already underlined in the previous section, the way that the academic eBook market works can make it possible to increase prices steeply while libraries have little option other than to accept, or face frustration from users.

Similarly, the work carried out by the library eLending project in Australia has underlined to what extent libraries’ choice is limited given their need to meet patron demand. As a result, rightholders have a broadly free hand to set higher prices, although of course may themselves lack the information to do so effectively.

The particular situation of libraries – in particular their mission, often set out in law, to meet the information needs of users – can make them particularly vulnerable to exercise of market power.

A competition investigation could take the information already gathered in Australia, and look to understand more broadly the degree to which libraries are constrained in decision-making, and to what extent this is allowing prices and terms for eBooks that would otherwise be impossible.

Clearly, this blog has drawn only on a limited number of examples, and can only point at possibilities, rather than draw any conclusions. Nonetheless, competition investigations into the library market are not a new idea.

In 2018, the European Universities Association proposed one looking at broader scholarly publishing, and a group of individual researchers have sought to launch a case on a specific company, as did UK researchers on the subject of non-disclosure agreements in particular.

So far, eBooks have tended not to attract quite the same attention as other fields, but with it uncertain for how long libraries are going to need to be primarily digital institutions, there may be value in a deeper look.

With public and institutional funding likely to become scarcer in the coming years, ensuring it is well spent is going to be a priority.

[Corrected on 26 May 2020 to underline that the reference to concentration in the academic market should have emphasised journals, rather than books]

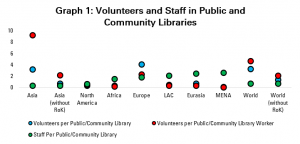

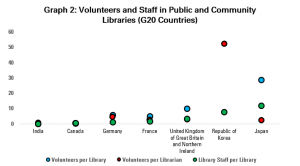

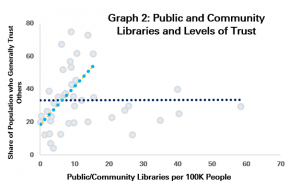

Graph 2 presents data for those larger (G20) economies for which data is available. Among these countries, it is relatively common to have more volunteers than FTE staff, with Germany, France, the UK and Japan in this situation.

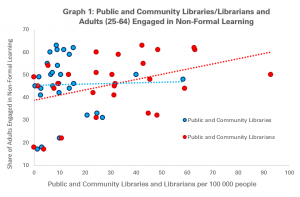

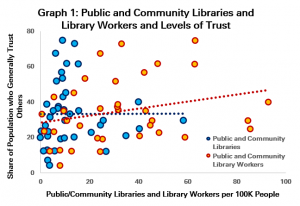

Graph 2 presents data for those larger (G20) economies for which data is available. Among these countries, it is relatively common to have more volunteers than FTE staff, with Germany, France, the UK and Japan in this situation. Graph 1 compares numbers of libraries and library workers (on the horizontal X-axis) with the share of the population who felt that other people could be trusted. Each dot represents one country.

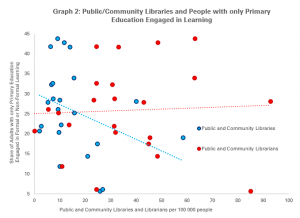

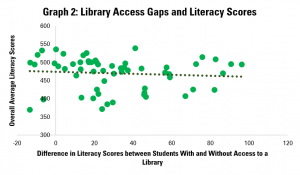

Graph 1 compares numbers of libraries and library workers (on the horizontal X-axis) with the share of the population who felt that other people could be trusted. Each dot represents one country. Graph 2 looks further into this question, including a trend line only for countries with fewer than 20 libraries per 100 000 people (i.e. one library per 5000 people).

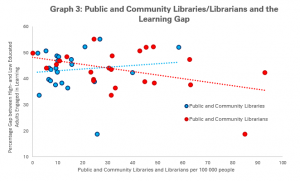

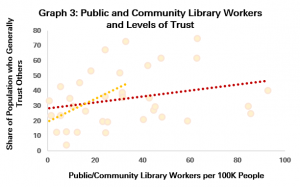

Graph 2 looks further into this question, including a trend line only for countries with fewer than 20 libraries per 100 000 people (i.e. one library per 5000 people). Graph 3 repeats the same process for countries with up to 40 public and community library workers per 100 000 people (the yellow line), coming to a similar conclusion. The relationship between library workers and trust is much stronger among countries below the threshold of 40 workers per 100K.

Graph 3 repeats the same process for countries with up to 40 public and community library workers per 100 000 people (the yellow line), coming to a similar conclusion. The relationship between library workers and trust is much stronger among countries below the threshold of 40 workers per 100K.