Over the past weeks, we have looked at data around digital divides, and to what extent these cross over with other potential divides in society – rich and poor, women and men, old and young, and those with higher or lower formal qualifications.

It is valuable to look at this because the results help understand to what extent the internet can act as a bridge across divides, or rather deepen them further.

Ideally, access to the web should help those who are disadvantaged find new opportunities and information in order to improve their own lives, as well as those of the people around them.

However, where access is lacking, the fortunate – those who can use the internet – can get ahead, while those without drop further and further behind. This has been abundantly clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, with children lacking internet access unable to take part in education in the same way as their better connected peers.

It is also the case for those facing unemployment. People seeking work can do so much more easily with access to the internet, both to find openings, and to develop skills or access support.

People who are retired can also risk being cut off without internet access, for example limiting contact with friends and family, governments services, and eHealth possibilities. Older people may also feel less confident online, and feel the need for additional support.

In both cases, libraries can provide a great way to ensure that everyone can get online and make the most of the internet.

This blog therefore looks at digital divides between those in work on the one hand, and those who are unemployed or retired on the other. Once again, data on internet use comes from the OECD’s database on ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals, while data on libraries offering internet access comes from IFLA’s Library Map of the World.

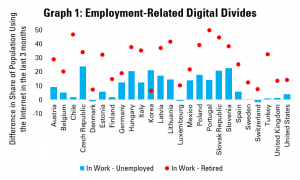

Graph 1 looks at the state of the employment-related digital divide, for countries for which data is available. In almost all countries, a greater share of people in employment have used the internet in the last three months than those who are unemployed.

Only Denmark, Luxembourg and Switzerland buck the trend. In the Czech Republic, Hungary, Korea, Slovenia and Slovakia, the gap is over 20 percentage points.

Meanwhile, in no country are retired people more likely to use the internet than people in work, with the gap reaching over 40 points in Chile, Lithuania, Portugal and the Slovak Republic.

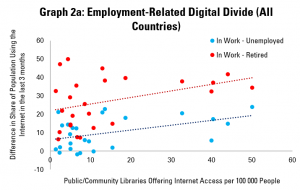

Graph 2a crosses these figures with those for the number of public or community libraries offering internet access. Each dot represents a country, with the number of public or community libraries offering internet access on the horizontal (X) axis, and the gap in shares of the population using the internet (employed minus unemployed (blue dots) or retired (red dots)) on the vertical (Y) axis.

As with previous weeks, putting together the figures for all countries suggests that there is a positive correlation between the number of libraries offering internet access per 100 000 people, and the size of the digital divide – clearly not an encouraging result!

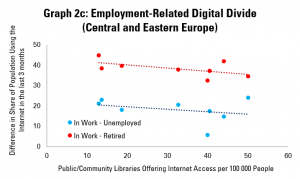

However, as we have seen in previous weeks, it is worth breaking out the results for Central and Eastern Europe, given the particular history of these countries

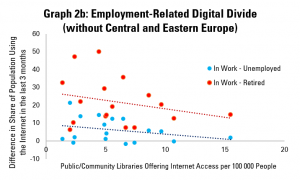

Graph 2b – using data from countries outside of Central and Eastern Europe – therefore shows a very different picture, in line with what we have seen in previous weeks. Where there are more libraries offering internet access, the digital divide faced by people who are out of work or retired, compared to their in-work peers, tends to be smaller.

Indeed, it appears that for every additional public library per 100 000 people offering access, the digital divide for the retired falls by 1 percentage point, and that for the unemployed falls by 0.55 percentage points.

Graph 2c repeats the analysis for countries in Central and Eastern Europe for which we have data, again indicating that where there are more libraries offering internet access, divides are smaller.

As always, the analysis carried out here cannot show causality – only correlation. However, it supports the argument that it is in societies with more libraries offering internet access that people who most need to access the internet face smaller barriers to doing so.

With COVID-19 risking exacerbating divides in societies, this is a powerful point to make in underlining why maintaining and broadening internet access through libraries matters more than ever.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.