We are happy to publish a guest blog, by Omo Oaiya, Chief Strategy Officer, WACREN and Pamela Abbott, Senior Lecturer in Information Systems, Head of the Information Systems Research Group, Global Challenges Research Fund Lead, Deputy Programme Coordinator at the Information School | The University of Sheffield.

This shares experience about an exciting collaboration which has brought together three key elements of meaningful internet access – connectivity, content and skills – demonstrating the potential of libraries in achieving the goal of giving everyone the opportunity to get the best out of the internet.

The emergence of open access in the early 2000s was arguably made possible by the spread of the internet, removing the need for an extensive infrastructure for printing and distributing journals.

Today, open access is well-established, and the talk is increasingly of open science – a broader term covering openness throughout the scientific process.

But for all the progress made, we cannot and should not forget that students and researchers using libraries in many parts of the world continue to face a combined challenge. Not only is connectivity too often poor, but even when it works, it can be hard to access relevant content.

Resolving these issues – and so realising the potential of open science approaches to accelerate research in all parts of the world – was the challenge taken on by the LIBSENSE initiative in West and Central Africa.

Core Team and Core Beliefs

The West and Central African Research and Education Network (WACREN) serves to bring connectivity to educational institutions across large parts of Africa.

Like other Research and Education Networks (RENs), WACREN aims to use a combination of economies of scale, expertise, and understanding of user needs to provide better access to the internet for universities, schools, and of course, their libraries.

Yet experience has demonstrated that connectivity alone was not enough to drive use. People needed a good reason to get online, and in the case of students and researchers, this meant relevant content.

This is what lay behind the LIBSENSE project, born out of tightening relations between WACREN and with partners who could help – COAR and its experience of developing open access repositories, EIFL and its work to train librarians and form consortia, and The University of Sheffield (TUoS) information school, and its research expertise in open access and information management.

The four organisations shared a commitment to promoting open science as the future of research in general, and in particular, as offering possibilities to allow researchers everywhere to contribute fully to scientific progress.

They also saw the value of collaboration, with specialists in infrastructure, repository design, and of course, content providers – students and researchers themselves – working together.

And they understood that to achieve this, it was vital to take the time to understand the attitudes, skills and priorities that different players had in order to bring them together.

While the core team of WACREN, COAR, EIFL and TUoS led this work, they made sure to keep things open, drawing on the strengths of a wider community and allowing greater reach than would otherwise be the case.

In Practice: Action for Progress

The combination of the strengths of the different parties involved in the LIBSENSE project has allowed for achievements that would have been impossible, or far slower, on their own.

A first key area of action has been around infrastructure support, with libraries supported to develop open access repositories. Drawing heavily on articles produced by staff and students within institutions, these repositories represent a key resource for learning and research, as well as a platform for researchers themselves. Thanks to REN infrastructures, these repositories can be connected, allowing for the development of thematic hubs, facilitating collaboration and accelerating discovery in areas most relevant for Africa.

A second area has been around capacity building. This proved crucial both as a means of ensuring that library staff are well placed to make best use of new digital infrastructures, but also to be able to engage in global initiatives around open access and open science.

Finally, work on policy development has focused on ensuring that rules and practices keep up with the opportunities created by the tools the LIBSENSE initiative has provided. The focus here has been not just on Institutional policies around publication, but also the development of national open science roadmaps.

Where Next?

In addition to successes of the growing community in creating and filling open access repositories, a key achievement of the LIBSENSE project has been to establish an incubator for further projects and collaborations. Through this, new tools and services have emerged to support the drive towards open science.

These collaborations do not only need to involve higher education libraries however! Public libraries are potentially key collaborators in efforts to democratise knowledge production.

Adopting the same model of collaboration between RENs and libraries, using the pillars of infrastructure support, capacity building, and policy development backed up by research, it could be possible to develop library hubs, support community learning, or better collect and draw on traditional knowledge, in addition to the wider advantages that working with RENs can bring.

The work of LIBSENSE, we hope, will not only endure in Africa but also provide a model and inspiration for collaborations elsewhere.

You can access the full article about the LIBSENSE project by Pamela Abbott on the IFLA website.

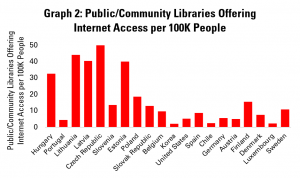

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

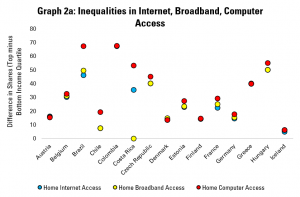

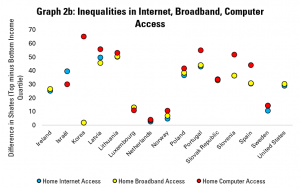

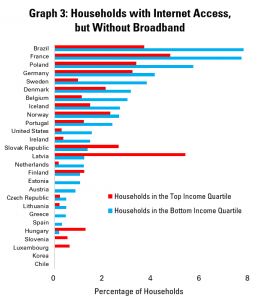

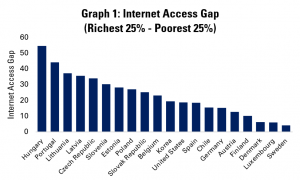

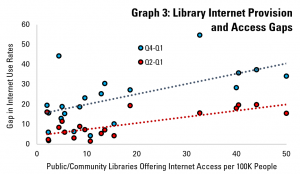

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens. We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

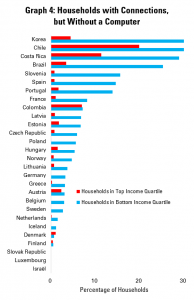

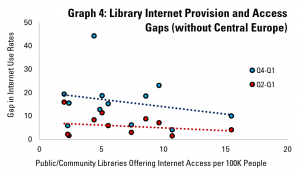

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access. As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.