Among the key themes on the table at the Transforming Education Summit taking place currently in New York is that of how to make the most of the promise of digital to help achieve education goals.

Of course, this is a multi-dimensional question. Education technology (EdTech) companies will promote digital programmes and products that claim to offer simple solutions to many of the challenges the sector is said to face.

Others will underline that too great a focus on the digital can lead to an undervaluation of the importance of access to a real teacher, in a real space. Digital tools should support the work of educators, not replace them.

Parallel concerns focus on the costs of digital in terms of privacy and choice, as well as how it can undermine freedoms granted by educational exceptions in copyright law. Both are areas which will need resolution if digital is to realise its potential to transform education for the better.

However, these questions are of course irrelevant if there is no connectivity in the first place.

This is the challenge that initiatives such as GIGA look to overcome. This is an exciting project launched by UNICEF and the International Telecommunications Union, with the goal of ensuring that every school around the world is connected.

It works by a combination of mapping the current situation of school connectivity, and then mobilising sources of finance, equipment and expertise in order to get schools online.

For libraries, as institutions with a clear educational mission, anything that contributes to making education more effective and inclusive is of course a good thing.

However, we also owe it to ourselves to point out that if leaders, nationally and internationally, are serious about realising the potential of digital to support education, it would make sense to expand the focus of any school connectivity programme to public and community libraries.

There are a number of key reasons for this.

First of all, there is the role of libraries in supporting the work of schools. Libraries and librarians have a critical role in complementing the work of teachers through provision of materials for teaching, as well as offering students possibilities to expand their horizons and practice literacy.

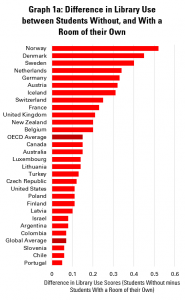

While such a role is often associated with school libraries, public and community libraries crucially also act here. In some countries, indeed, they formally fulfil the role of school libraries. Elsewhere, they support literacy and discovery, as well as providing a space for homework, without such an official link. This can be particularly important for children who do not benefit from space at home or strong parental support.

Clearly, these are roles that are supported when libraries can provide internet access, expanding both the range of content and services that can be offered, and making them far more interesting as a place to do homework.

Secondly, libraries have a well-established role in supporting school-readiness. The value of exposing children to a range of language in their early years is well recognised, stimulating development.

Of course, much of this work takes place in person, through activities such as story-times and those based on play. However, again, access to wider resources, including recorded story-times online, or ideas and suggestions for other means of supporting learning, has a real value. This can be particularly the case for materials in minority languages for example.

Once again, internet connectivity can play a big role here, broadening the range of support that they can offer to families with younger children, but also allowing them to draw on new ideas to maximise effectiveness.

Finally, although far from the least important, is the role of libraries as portals, partners and providers in lifelong education.

Libraries can both provide a space where people of all ages can access, in a quiet, safe space, library materials, and serve as a location engaging with learning provided by others. They can both organise their own courses and less formal support for visitors, and work with others to expand massively the range of opportunities they offer.

In short, once people have got beyond school age, libraries are often the primary place to look for lifelong learning opportunities. And of course, once again, they are best able to fulfil this role when they are connected to the internet, both as a source of information, and of course as a pre-condition for eLearning.

To conclude, the drive to ensure school connectivity is an important contribution to the goal of transforming education. Nonetheless, it does not resolve every challenge. Some – such as ensuring that we do not undervalue the role of in-person education, or of course the right to a private life – will require further reflection.

However another – how to support pre-schoolers, school-age children without the luxury of a quiet space and internet connection, and of course the adult education community – can be answered, at least in part, by ensuring that libraries are connected alongside schools.

We hope that in rolling out the GIGA initiative, the importance of connected libraries can be reflected and acted on, in support of the transformation of education.

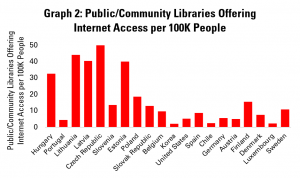

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

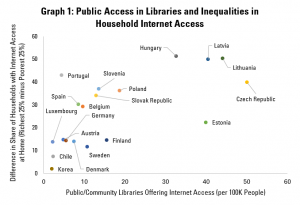

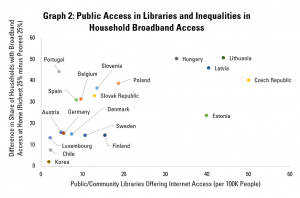

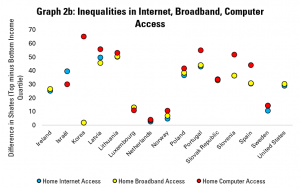

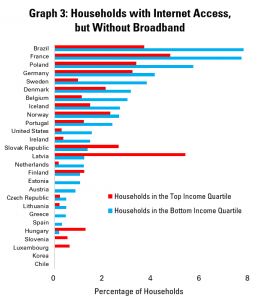

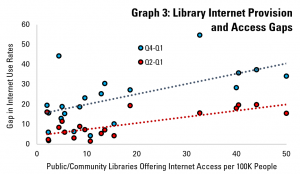

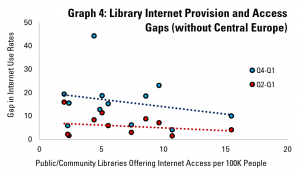

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens. We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

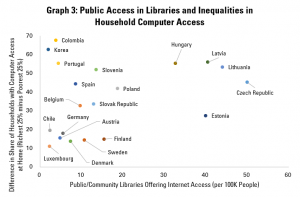

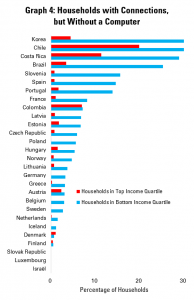

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access. As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

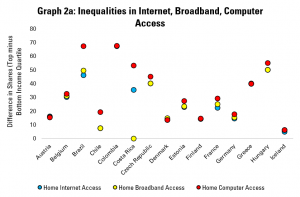

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.