The theme of this year’s World Social Justice Day is ‘A Call for Social Justice in the Digital World’.

The focus is timely – the last decades have seen digital technologies play a more and more central role in the economy, shaping the way we work, and the type of work we do.

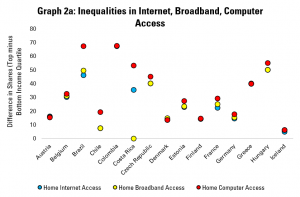

As the United Nations’ own note for this year’s commemoration underlines, this has brought new opportunities for employment and entrepreneurship which, previously, would not have been imaginable. It highlights that those who are left offline therefore risk enjoying fewer opportunities, while others move further ahead.

However, there are also concerns, notably around platform-based business models and their impacts, both on competitors and their own employees or contractors. Within the workplace, tracking of employee activity raises the prospect of greater surveillance and reduced wellbeing.

These too risk driving inequalities between companies and between individuals by giving some greater opportunities than others.

As such, the UN makes a case for efforts to define responses and actions, firstly to tackle the imbalance between those who are off- and online, but also to address challenges that give more possibilities in the digital world to some than to others.

But what then about libraries?

As this blog will argue, efforts to build digital social justice today can take inspiration from the long-standing work of libraries to promote information social justice (a term explored in the next section). Furthermore, our institutions are well placed not only to contribute to practical efforts in the field, and to support further reflection.

Information Social Justice

While it may not often be talked about in these terms, the work of libraries to provide universal access to information is could be described as promoting information social justice.

This work is about giving everyone the opportunity to access the information they need to fulfil their potential, either through collections within a library, or through document supply.

It is also about giving everyone the possibility to use information effectively, through the application of copyright exceptions that would otherwise put many works out of reach, and through the provision of skills and support.

Yet it is not just a question of opening the doors to all, but also taking proactive efforts. Public libraries in particular have a mission, as set out in the UNESCO-IFLA Public Library Manifesto, to make particular efforts to ensure that everyone benefits.

This work supports employment and entrepreneurship for all, as set out in our research piece for this day two years ago, alongside a wide variety of other economic, social, cultural and civic goals.

Digital Social Justice Implementors

Increasingly, the work of libraries to promote information social justice takes place through digital means of course.

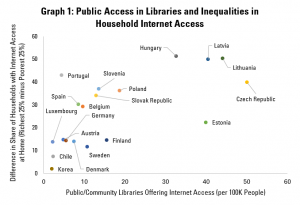

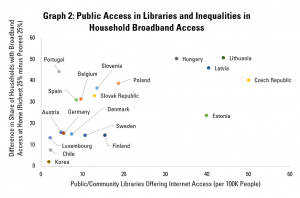

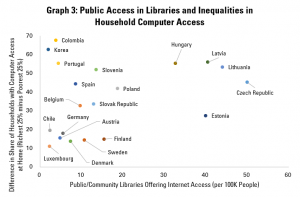

Connecting libraries to the internet and opening access to users has allowed our institutions to provide access to a greater volume of information. At the same time, it has also required further work to help users improve their ability to navigate through what is there.

This can stretch from helping people to look for work online and prepare digital CVs, to holding coding classes that can open the way to new jobs. The need for more advanced information literacy, in particular to understand how information is created, shared and presented, is clear.

Crucially, these services are provided in a way that looks to respect the principle of universality, with efforts to ensure that no-one should face unjustifiable barriers to accessing and using digital tools to improve their own lives.

The role of libraries in delivering on effective connectivity and digital skills strategies has already been recognised by many governments. Nonetheless, this is not to say that the situation is perfect everywhere. There is always space to share ideas, innovate and improve practice in order to reach further.

Joining the Debate

In addition to their own efforts, a key determinant of libraries’ ability to contribute to digital social justice will be the choices made by governments themselves.

The experiences – and values – of libraires can have much to contribute in discussions around how the internet should operate in order to promote the ability of everyone to participate actively in economic, social, cultural and civic life.

IFLA has engaged on these questions for a number of years, with statements on privacy, net neutrality, the right to be forgotten, digital literacy, internet shutdowns and beyond. In each case, there has been an emphasis on how to ensure that restrictions on universal access to information are minimised, protecting the capacity of all people to draw on information without unjustified restrictions.

In each case, poor decisions can leave those with fewer resources exposed to greater exploitation of their personal data, a narrower range of materials available (at reasonable speeds), and less ability to exploit the opportunities the internet presents.

Libraries also bring in extensive experience of acting as ‘platforms’, providing access to works by others in an equitable fashion. To do this, they must negotiate questions around balancing human rights, respecting the law, and accountability.

In doing so, they rely on professional judgement and ethics that could contribute much to discussions today around the role of platforms.

Conclusion

With digital technology advancing rapidly, the combination of measures needed to ensure digital social justice – from personal connectivity and skills to wider regulation – are evolving, even if the goals of social justice are lasting. This in turn requires a process of ongoing learning and action not only amongst governments, but also among all relevant stakeholders.

In this process, libraries have much to offer, both in delivering on fundamentals such as internet access and providing a platform for skills development, and in contributing experience and expertise to wider discussions.