World Children’s Day is the anniversary of signing both the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1959, and the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1989.

It is an opportunity to focus on ensuring that the rights and interests of children are understood, and incorporated into decision-making at all levels.

This year’s theme is a Better Future for Every Child, concentrating on the impacts of inequalities on children, and the need to combat child poverty. It draws, in particular, from the economic and social divides exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which demonstrated how different factors can interplay to lead to worse outcomes.

This focus also recalls the fact that the experience of poverty in childhood is too often associated with negative outcomes later in life, such as higher unemployment or lower incomes, poorer health, and beyond.

This link begins early, with poverty all too often correlating with lower literacy and other skills leading to less good education performance. This can risk reinforcing poverty over time, with poor children turning into low-income parents, whose own children then face the same challenges.

In the long run, putting an end to child poverty means increasing income levels. A key way of achieving this is by breaking the link between economic poverty and other negatives, such as low literacy and wider educational outcomes.

The strength of this link can come from a variety of factors: there may be fewer resources available at home, parents may be less able to help with homework and language development, families may participate less frequently in cultural events that can develop a taste for reading, and children may not have a space or quiet for learning.

Library interventions combatting educational inequality

Clearly, schools have a key role to play in tackling this situation, with skilled teachers with adequate resources helping ensure that children from poorer backgrounds genuinely do have the same chances as their better-off peers.

Complementing these, however, are great library services for children, through both school and public or community libraries, drawing on their unique potential to support learner success. This role that libraries play is well documented (here and here, to give just two examples).

A first contribution comes through the wider work of libraries in giving access to materials that help develop ideas and expand horizons, something that may be particularly important for young people growing up without access to a wider range of experience.

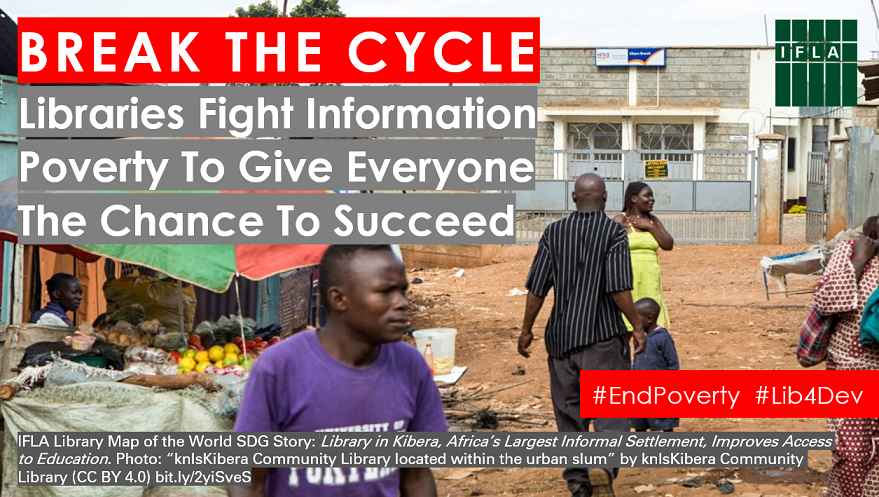

They can run programmes focused on poorer communities, such as KidsREAD in Singapore, targeted at improving the English language skills of young people who risked falling behind otherwise, and run by the National Library Board. Similarly, Kids on the Tab in Kibera, Kenya, worked through libraries to complement the schooling of children from poor areas, contributing to much improved exam results, which in turn open up new possibilities. Libraries can also be useful venues for promoting programmes aimed at encouraging better educational outcomes, such as the MathsWhizz programme in Kenya.

A particularly important activity can be summer reading clubs, addressing the fact that over the long break, children without opportunities to learn and develop literacy skills at home risk falling behind their peers, leading to lower performance and frustration when they return. Holiday breakfast clubs can serve a similar purpose, while also tackling food insecurity. Homework clubs also help children who may lack a quiet space at home to work.

Libraries also play an important role in supporting school-readiness, ensuring that children are able to engage properly when they start formal education. A number of countries have adopted initiatives based on or similar to Bookstart, for example Boekstart in the Netherlands, Kindertreff in Switzerland, Start Life with a Book in Czechia, and Better Beginnings in Australia. They typically involve the provision of age-appropriate materials from a young age, and then ongoing support, including in cooperation with doctors, in order to keep an eye on language development.

While these are often universal programmes, a key goal is to support those families which may not have other opportunities, or children with difficulties that may hold them back at school (such as disability, anxiety, or attention deficit).

Connected to this, libraries (both school and public) can support family learning, helping to engage parents in the effort to develop children’s literacy skills, and potentially brining direct benefits to them as well. Furthermore, they serve as community convening spaces, and bring in an important experience of supporting personalised learning, as underlined by the Urban Libraries Council.

Even outside of specific service offers, research demonstrates that children from poorer background report relying far more on libraries than their richer peers.

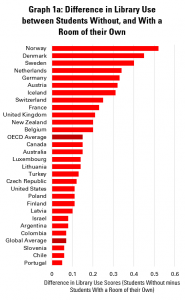

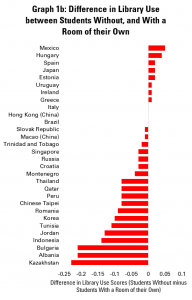

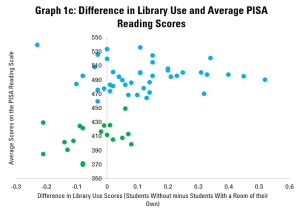

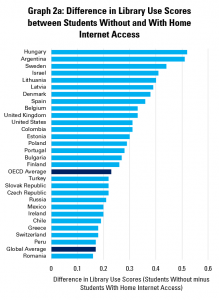

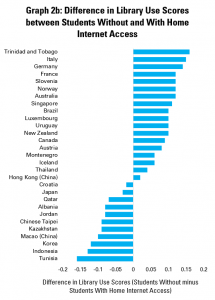

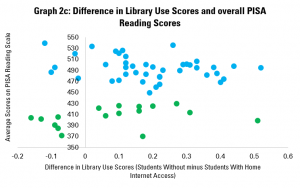

IFLA’s Library Stat of the Week series drew on data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) to show how children who don’t have a room of their own, have parents with lower qualifications, or who come from foreign language or immigrant backgrounds tended to have greater levels of dependence.

Further research using the same data just for the US has echoed this point, noting that even if levels of usage are the same, this usage will be more important for children who don’t enjoy access to space, resources and connectivity at home. Work in the UK underlines the same, focusing on the reliance of poorer children on public libraries.

They also help by providing internet access and equipment that families may not be able to afford, or simply extending opening hours (both providing a space for young people, and allowing parents to take on full-time work).

Indeed, in situations where children face insecurity and deprivation at home and outside, libraries can act as places of retreat and safety, both in richer countries, and in others facing serious endemic violence problems, such as Brazil and Colombia. Village and mobile libraries can extend possibilities to access information and technology to rural areas, which often also face higher levels of child poverty, as in India and Burkina Faso, or those which are remote, such as the Galapagos.

From potential to practice

However, the continued existence of education inequality, to the detriment of young people from poorer backgrounds, makes it clear that there is a lot still to do.

To some extent, there is work to do within our field, drawing on existing good practices. For example, as the Literacy Trust in the UK notes, it is important to reach out, given that there may be a reluctance to use libraries in some circumstances. Libraries’ reputation as a quiet place, only for the more highly educated, can represent a barrier to overcome. There is a risk that the people who need library services most simply don’t take the opportunity.

Libraries need to be able to reach out to poorer children where they are, rather than relying on traditional tools such as brochures, with cooperation with schools offering a powerful possibility in the case of public libraries at least, as underlined by the Urban Libraries Council.

There may even be an opportunity, as libraries open up following the pandemic, to do things differently and to engage people who previously never participated in library activities. For example, creating small public libraries in people’s homes in Foshan, China, helped increase outreach to families in deprived areas who would not otherwise come to existing institutions.

The way in which services are provided also matters. It is important not to create stigma around using services targeted towards children on low incomes, as underlined by the Child Poverty Action Group.

Skills also matter, a point also underlined by the Urban Libraries Council, and which lies at the heart of the Library at School programme in the Netherlands. So too does the ability to evaluate the impact of the work of libraries on educational outcomes among children facing poverty.

However, for our institutions to be able to fulfil their potential, they also depend on adequate resourcing and support. Yet all too often, it is poorer schools that aren’t offering school library services, a point made by the UK Children’s Laureate recently, but which has been known for over a decade.

As she set out: Millions of children, particularly those from the poorest communities worst hit by the pandemic, are missing out on opportunities to discover the life-changing magic of reading – one that OECD research suggests is a key indicator in a child’s future success. How can a child become a reader for pleasure if their parents or carers cannot afford books, and their primary school has no library, or that library is woefully insufficient?

Some have worried that cuts to library services happen quicker in less well-off areas, with impacts both on collections, and on spaces and staffing. In both cases, under-investment risks leading to unrealised potential to support investment in combatting inequality in education and literacy.

In conclusion, this year’s World Children’s Day provides an important reminder of the need to act on education and literacy as part of wider efforts to combat inequality and poverty among children. Libraries – both school and public – have a strong and proven role in doing this, drawing on their unique strengths.

Yet with significant challenges remaining, often exacerbated by the pandemic, these good practices need to be taken as a call to action, both within our field, but also – and perhaps more importantly – to the governments and others that determine what resources libraries have, and how they can work.