In the last couple of posts, we have looked at the relationship between the availability of public libraries offering internet access and digital divides.

Using data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), we have looked at gaps in levels of internet use among richer and poorer households, between older and younger people, and between women and men.

In each case, it appears that where there are more public libraries offering internet access, these gaps are smaller.

This week’s post looks at digital divides between people with lower and higher levels of formal education.

Clearly, education is often a key determinant of economic success later in life. Yet not everyone has the possibility to gain qualifications early on, for a variety of reasons. What is important then is to have a second chance – an opportunity to learn in other ways, and even gain qualifications.

We have already shown that societies with more public library workers tend to have higher shares of adults in general engaged in lifelong learning (Library Stat of the Week #20). This also highlighted that in general, where there are more public library workers, the gap in rates of participation in lifelong learning between the high- and low-educated is less.

The internet is a key way of finding and accessing learning opportunities. Especially during COVID-19, but clearly also before, online learning has become more and more important.

Therefore, looking at the digital divide between those with high and low levels of education (i.e. the difference in percentages accessing the internet at least once in the last 3 months), we can also build up a sense of whether libraries may be helping ensure that those with fewer qualifications are getting a second chance.

Once again, data on internet use comes from the OECD’s database on ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals, while data on libraries offering internet access comes from IFLA’s Library Map of the World.

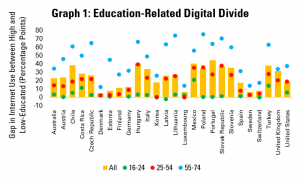

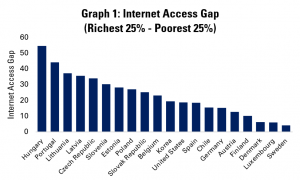

Graph 1 looks at the state of the education-related digital divide in general. Looking at the population as a whole, some countries demonstrate dramatic differences.

For example, there is a gap of over 40 percentage points in levels of internet use among people with high and low levels of formal education in Hungary, Mexico and Portugal. It is only in Denmark, Estonia, Luxembourg, Sweden and Switzerland where the gap is smaller than 10 percentage points.

In every single country, the gaps are wider among people aged 55-74 than among younger generations. Gaps are also wider among 25-54 year olds than among 16-24 year olds in every country except Luxembourg.

The size of gaps matters, and arguably more among older workers. In general, it can be more difficult for older workers to find new jobs if they become unemployed. The internet can help address this, if it is available.

More broadly, this raises the possibility that not only does having less formal education mean that people are less likely to be internet users, but that in turn, difficulties in accessing the internet may stand in the way of efforts to find and make use of opportunities to improve lives, creating a vicious circle.

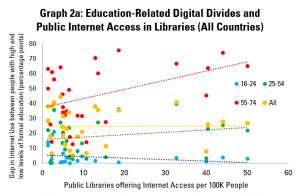

Graph 2a compares these figures (including broken down by age group) with those for the number of public libraries per 100 000 people offering internet access.

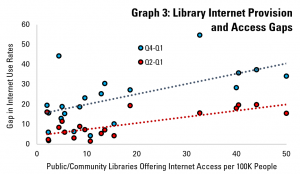

The finding is not necessarily encouraging – where there are more public libraries, the gaps are wider. However, this is also in keeping with previous analyses when we have looked at Central and Eastern Europe (which has its own particular history) and all other countries together.

Graphs 2b and 2c look at the ‘rest of the world’ and Central and Eastern Europe separately.

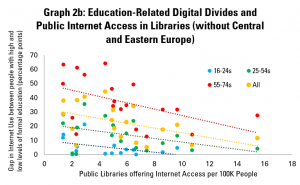

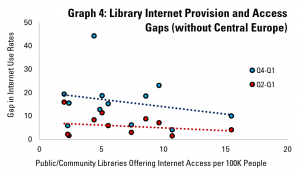

Graph 2b – looking at all countries for which data is available, except those in Central and Eastern Europe – shows a correlation between having more libraries offering internet access, and smaller digital divides.

Indeed, it appears that on average, for every 1 extra public library per 100 000 people offering internet access, the digital divide drops by 1.7 points. Looking only at the digital divide among older people, the divide shrinks by 2.2 points.

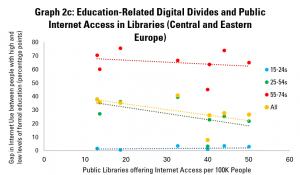

Graph 2c looks at Central and Eastern Europe in particular, and finds similar conclusions, at least for people aged 25 and above, and for the population as a whole. Once again, where there are more public libraries offering internet access, the education-related digital divide is smaller.

As we underline in almost all of these posts, correlation does not mean causality. It is of course possible that the sort of society that invests in libraries also invests in the sort of minimum income support that ensures that everyone has a good chance of being able to buy a computer and internet connection.

Nonetheless, sample-based work, as well as anecdotal evidence, does suggest that libraries can provide a vital opportunity for those with fewer resources to get online, and access second chances – for education, employment, and simply personal fulfilment.

The results presented here do support the argument that libraries can help prevent the digital divide becoming a vicious circle.

Next week, we’ll be looking at the digital divides that exist between people who are in work, and those who are unemployed, or retired.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.

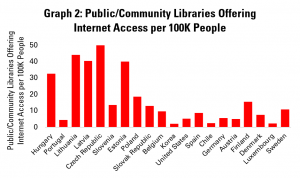

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

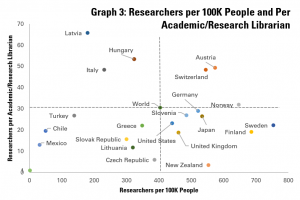

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens. We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access. As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

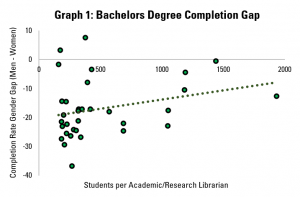

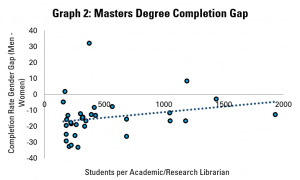

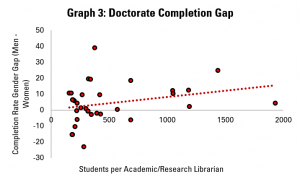

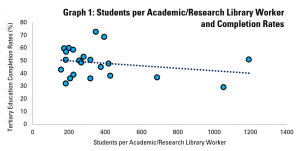

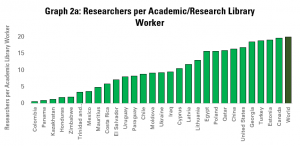

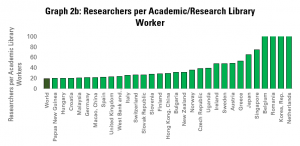

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.

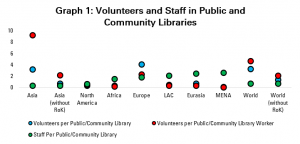

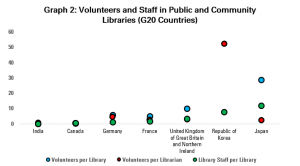

Graph 2 presents data for those larger (G20) economies for which data is available. Among these countries, it is relatively common to have more volunteers than FTE staff, with Germany, France, the UK and Japan in this situation.

Graph 2 presents data for those larger (G20) economies for which data is available. Among these countries, it is relatively common to have more volunteers than FTE staff, with Germany, France, the UK and Japan in this situation.