Eric Klinenberg’s book, Palaces for the People, has popularised the idea of libraries as key parts of the ‘social infrastructure’ of the communities they serve.

This role matters, because social infrastructure supports the development of social capital – strong connections between people, often associated with trust – commonly seen as a key driver of development.

For example, when there are strong levels of trust between people, they need to spend less time protecting their own interests, and can cooperate more easily to achieve other things, such as a strong economy, inclusive social policies, or action to tackle climate change.

Trust can be built through common references and rules, often themselves developed through contacts between people. Libraries – especially public and community libraries – support both, allowing members of communities to meet and exchange in a shared space, often supported by shared resources and heritage.

Klinenberg looks at the role of libraries in building social cohesion at the level of individual cases. But what can we tell at the macro-level?

To do this, we can cross statistics from IFLA’s Library Map of the World with those from the OECD’s Society at a Glance 2016 publication. As previously in our Library Stat of the Week series, we have looked at figures both for numbers of public and community libraries and library workers.

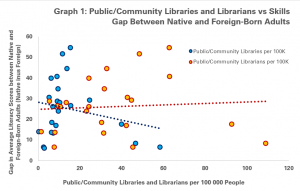

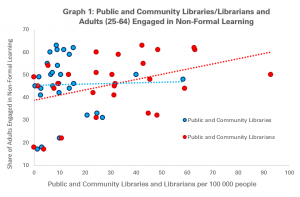

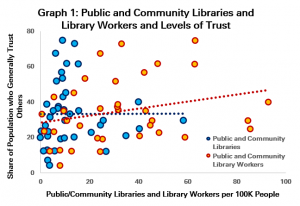

Graph 1 compares numbers of libraries and library workers (on the horizontal X-axis) with the share of the population who felt that other people could be trusted. Each dot represents one country.

Graph 1 compares numbers of libraries and library workers (on the horizontal X-axis) with the share of the population who felt that other people could be trusted. Each dot represents one country.

This graph indicates a positive but relatively weak correlation between numbers of library workers and levels of trust, and relatively little relationship at all between numbers of libraries and trust.

There is a positive story in here, as regards library workers of course. As we have indicated in previous posts, it is clear that the presence of librarians can play a decisive role in ensuring that libraries achieve their outcomes.

However, as concerns the number of libraries, the figure is perhaps a little disappointing. Nonetheless, from looking at the graph, it stands out that the relationship may vary as the number of libraries per 100 000 people grows.

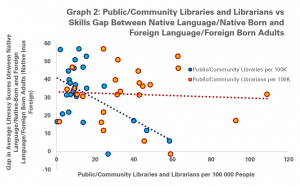

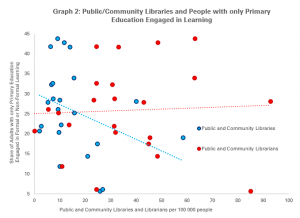

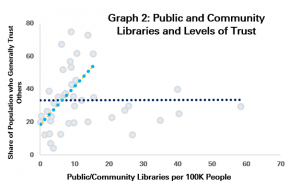

Graph 2 looks further into this question, including a trend line only for countries with fewer than 20 libraries per 100 000 people (i.e. one library per 5000 people).

Graph 2 looks further into this question, including a trend line only for countries with fewer than 20 libraries per 100 000 people (i.e. one library per 5000 people).

The difference here is striking. There is a much stronger positive correlation between numbers of libraries and trust in countries with up to 20 libraries per 100 000 people (the light blue line), but after this, the relationship becomes much flatter.

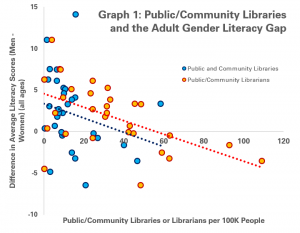

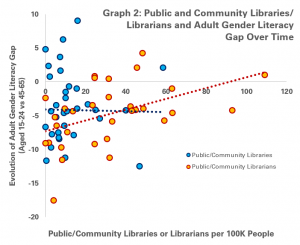

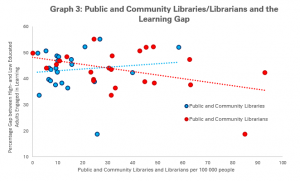

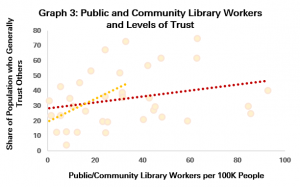

Graph 3 repeats the same process for countries with up to 40 public and community library workers per 100 000 people (the yellow line), coming to a similar conclusion. The relationship between library workers and trust is much stronger among countries below the threshold of 40 workers per 100K.

Graph 3 repeats the same process for countries with up to 40 public and community library workers per 100 000 people (the yellow line), coming to a similar conclusion. The relationship between library workers and trust is much stronger among countries below the threshold of 40 workers per 100K.

This finding is an interesting one, and would support the conclusion that in particular in countries which invest less in libraries (as measured by the number of public and community libraries and library workers), there are significant gains to be had from strengthening the field (or costs from making cuts).

Beyond a certain threshold, the gains (or costs) in terms of social cohesion are less dramatic, although as seen in previous posts, there may be impacts in other fields, such as skills or equality.

As always in this series, it is important to note that correlation is not causality. Further research would be needed to assess to what extent other factors may be in play, and it is of course also possible that societies that invest more in libraries tend to be those who believe more in supporting communal services and activities.

Nonetheless, the data here does provide a useful indicator that countries with more public and community libraries and library workers, there tends to be higher levels of social cohesion.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.

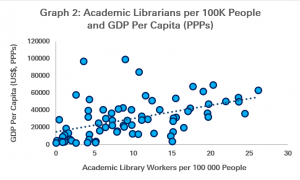

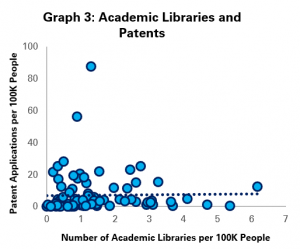

In other words, while in general, richer countries tend to have more academic library workers, this is not always the case. Some very rich countries have relatively few, while some poorer countries have relatively many.

In other words, while in general, richer countries tend to have more academic library workers, this is not always the case. Some very rich countries have relatively few, while some poorer countries have relatively many. In this graph, a negative figure on the vertical axis indicates that they are producing relatively few publications for their level of GDP per person, while a positive one indicates higher publishing rates.

In this graph, a negative figure on the vertical axis indicates that they are producing relatively few publications for their level of GDP per person, while a positive one indicates higher publishing rates.

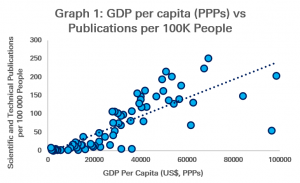

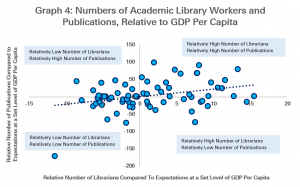

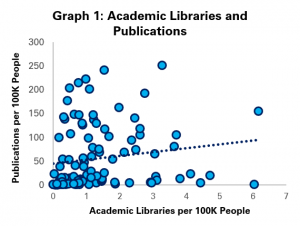

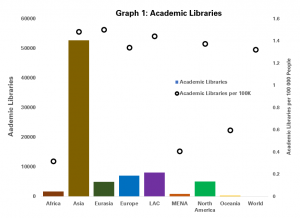

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1).

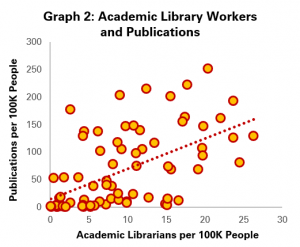

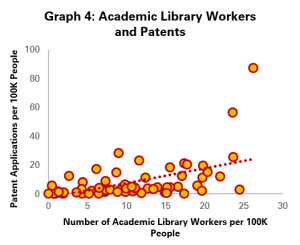

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1). Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people.

Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people. Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

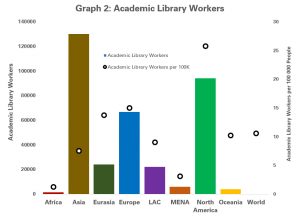

Graph 2 goes into more depth, breaking down numbers of academic library workers per region, and relative to overall population sizes. Once again, Asia comes out on top in terms of numbers of workers at almost 130 000 (not including India this time), with North America a little way behind on 93909.

Graph 2 goes into more depth, breaking down numbers of academic library workers per region, and relative to overall population sizes. Once again, Asia comes out on top in terms of numbers of workers at almost 130 000 (not including India this time), with North America a little way behind on 93909.