Libraries were often early adopters of digital technology, both for their own internal operations, and in support of their users.

By installing computer terminals and allowing for public access, they have given millions their first taste of the internet, in an environment where they could feel comfortable and supported in trying something new.

It is also well understood that that libraries can play a key role in bringing the unconnected online through providing this sort of public access. In some cases, this can act as a stepping stone towards private access, in others, an essential backstop for those unlikely ever to get a connection or device at home.

Frequently, those in the greatest need of this support are the poorest members of a society, who may not be able to commit to regular monthly payments, either for fixed or mobile internet. Instead, they can be stuck with pay-as-you-go options which end up more expensive.

This blog, the first in a sub-series, therefore looks at the connections between the digital access gap and the presence of libraries offering internet access. It draws on OECD statistics on internet access and usage for households and individuals, and IFLA’s own Library Map of the World.

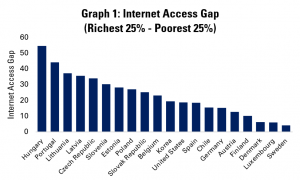

First of all, it is worth understanding the scope of the challenge. Graph 1 indicates the differences in internet access rates (use of the internet in the past three months) between people from households in the first (poorest) and fourth (richest) quartiles of the population.

In this, only three countries – Denmark, Luxembourg and Sweden have a gap of less than 10 percentage points. Meanwhile, in Hungary, the gap is almost 55 percentage points – nearly 92% of people from richer households have accessed the internet, but barely 37% of those from poorer ones.

Interestingly, only one of the nine countries with the biggest gaps does not belong to the former Eastern bloc – we will return to this point later.

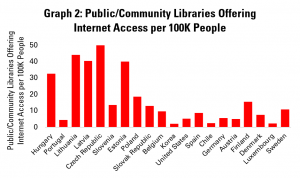

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

Lithuania and Latvia also have more than 40 public libraries offering internet access per 100 000 people, and Estonia is only a short way behind.

Again, it is noticeable that most of the countries with high numbers of libraries offering internet access are from former Eastern Bloc countries.

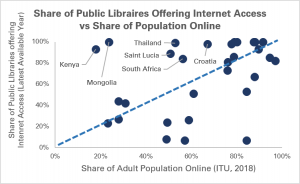

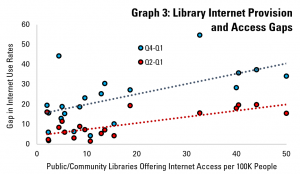

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

This shows a correlation between the number of libraries offering access and the gap in access between rich and poor. This applies both for the difference between the richest 25% and the poorest 25% (4th quartile minus 1st quartile), but also between those roughly in the middle and those at the bottom (2nd quartile minus 1st quartile)

On the one hand, this suggests that there is – fortunately – the infrastructure in place in order to help bridge this divide. The challenge, then, is to ensure that the possibilities that libraries provide turn into smaller access gaps in reality.

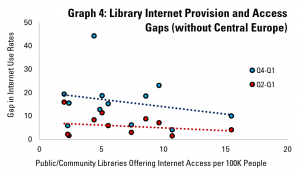

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

Here, in fact, we can see that the correlation goes in another direction, suggesting that having more libraries offering internet access tends to be associated with a smaller gap between rich and poor in terms of internet access.

The analysis presented here raises interesting questions – what more can be done to realise the potential of connected libraries to close the gap between rich and poor in terms of internet access in countries of the former Eastern bloc? Can we take the more positive correlation between equality and the existence of libraries elsewhere as a positive?

Next week, we’ll explore the same question from different angles, including age and level of education.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.