Last week’s Library Stat of the Week started to explore the data available from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Programme for International Student Assessment (OECD PISA) regarding libraries and inequalities.

Based on a series of questions about the type of use that students (15 year olds taking part in the test) make of libraries, and how often, the PISA 2009 database provides an index of use of libraries.

By looking how different groups, on average, score on this index (running from -1 (no use) to +1 (extreme use)), it is possible to get a sense of whether there is relatively more or less dependence on libraries, according to different characteristics. As such, this provides valuable insights into how the benefits (or pain) of investment in (or cuts to) libraries may fall.

Following on from looking at differences in library usage between 15-year olds who have a 1st or 2nd generation immigrant background, as opposed to ‘native’ students, this week looks at two indicators of disadvantage – whether children have a room of their own at home or not, and whether they have household internet access or not.

Both of these are not only signs that a student may come from a less well-off background, but can also have a direct effect on their ability to benefit from education. The possibility to read and study quietly, and to make use of all that is available on the internet, are powerful.

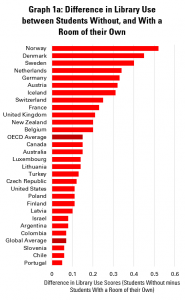

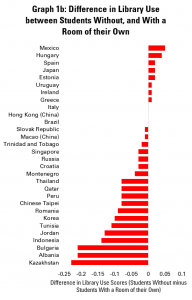

We start by looking at differences between students who do, and do not, have a room of their own.

Graphs 1a and 1b do this for each country for which data is available, giving a figure for the difference in the index of library use between students who do not, and do, have a room to themselves. A bar to the right shows that students who do not have such a private space make more use of libraries than students who do, while a bar to the left shows the contrary. The longer the bar, the bigger the difference.

Overall, it shows that in OECD countries, students who do not have a room for themselves score 0.15 points higher on average on the library usage index, while globally, the figure is 0.07. The biggest differences are to be seen in Scandinavian countries, as well as the Netherlands and Germany.

In 38 countries, students without a room of their own make more use of libraries than those who don’t. In 19 countries, it is the other way around, while in 3, there is no difference.

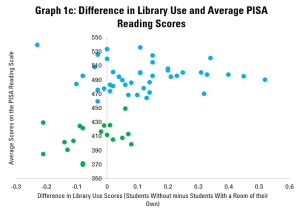

Graph 1c looks at whether there is much difference in this level of reliance on libraries depending on overall average reading scores. As in last week’s post, there appear to be two groups of countries – with richer countries which tend to score higher in blue, and developing countries tending to score lower in green.

Within each group, however, there is little correlation between the level of reliance on libraries by students without rooms of their own, and overall reading scores. In other words, it seems not to matter much whether a country is a high or low performer overall – those who are disadvantaged continue to make strong use of libraries.

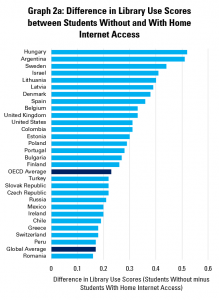

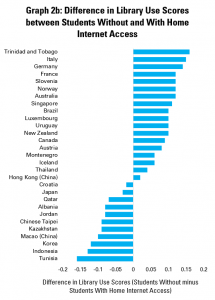

Graphs 2a and 2b replicate the analysis in Graphs 1a and 1b, but rather comparing scores for library use between students who do not, and who do, have internet access at home.

The differences here are even stronger, with an OECD average difference of 0.23 and a global average of 0.17, illustrating that globally children without home internet access rely more heavily on libraries than those who don’t.

In 48 countries out of 59, libraries appear to be more important for children without home internet access than for those with it, while only in 11 do children with internet access at home make more use of libraries than those who don’t. Interestingly, the countries with the highest differences in usage are different to the ones which come top when looking at students with rooms of their own.

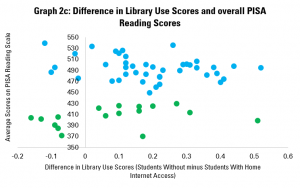

Graph 2c then repeats the same logic as Graph 1c, looking at whether there is any reason to believe that the connection between lack of a home internet connection and library use is stronger or weaker depending on overall literacy scores.

The result – as in the case of Graph 1c – is that there is no clear connection, either in the group of lower performers or the group of higher performers. In other words, it does not matter much how well a country performs overall on literacy, library use tends to be higher among students without an internet connection at home.

The overall conclusion of this blog is that the evidence indicates that, in general, students who face barriers to benefitting from education due to their home environment tend to rely more on libraires. The corresponding argument is then that when library services are cut back, the pain will be higher for those who already have fewer resources or options.

Next week’s post will look at another dimension of inequality – the highest level of education achieved by parents.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.