Public libraries, as underlined in the IFLA-UNESCO Public Library Manifesto, have a clear mandate to serve their entire communities. As such, they can be described as ‘universalist’ – for everyone, not just a selected group.

This is an increasingly unique characteristic of public services at a time of growing pressure to show that resources are being used most effectively.

This part of the nature of libraries’ work can lay them open to the accusation that they are serving people who do not need help, for example through lending books that readers could buy.

However, it is also backed up by the universalist message of the Declaration of Human Rights, itself cited in the IFLA Statement on Libraries and Intellectual Freedom.

The question of whether and how far a public service should be limited touches on a long-standing debate in social policy about the merits of universal, as opposed to targeted benefits and services. It is also one where the work of one key contributor – Amartya Sen – has received a Nobel Prize.

So what does Sen tell us about the relevant merits of targeting vs universalism, and how does this affect libraries?

Targeting vs Universalism

On the side of those favouring targeting, there is an expression of concern about the apparent waste of public (or private) money that comes from serving people who do not need services.

Money and effort which could be spent on the poor goes to the rich. They argue that targeting can ensure that most – if not all – goes to those who are ostensibly in greatest difficulty.

The implication is that it is only people below a certain income who are able to access certain services or benefits. And too often, services for the poor risk becoming poor services.

However, there are strong criticisms of this approach, not least those of Amartya Sen, as mentioned in the introduction.

The means of working out who is eligible or not are far from perfect. It can be difficult to measure income – some will lie in order to gain support, others will hide their poverty out of pride.

This point is an important one. In many countries, it is seen as shameful to be poor. People do not want to admit that they do not have money, and so will avoid situations where they have to do this.

Targeting, it is argued also creates the risk of reducing incentives to improve your situation, given that this could lead to a withdrawal of support. Why work those extra hours that could take you over a certain threshold when it means you might end up worse off once support is cut?

Finally, targeting implies that the population involved are just that – targets – rather than agents in their own right, something that also risks damaging the self-respect of beneficiaries.

Sen does note that some adaptation of services may be valuable, for example due to disability, or social status. These can have a useful levelling-up effect.

However, they should come against a backdrop of universal support and services. Indeed, such an approach tends to be associated with greater overall equality.

Universalism in the Library

The work of libraries not only provides an example of universalism at work, but also brings in another key aspect of Sen’s thinking – that of ‘capabilities’.

Linked to his objection to the idea of the poor as being ‘targets’, he focuses on how to ensure that people in difficult situations have the possibility to improve their lives. These ‘capabilities’ allow for ‘functionings’ – taking part in economic, social and cultural life.

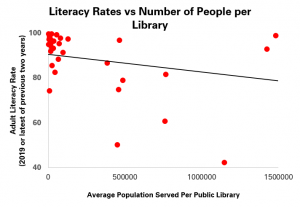

Key capabilities in this regard are skills such as literacy and the right and possibility to share and receive information.

Libraries provide these, as underlined in the Development and Access to Information report. And of course, crucially, they do this in a universal way, building capabilities for all.

In doing do, they provide a means of participating in culture which neither excludes people because they have too little money (like the market), or because they have too much (risking stigmatising users as being poor).

The same goes for education and research.

Finally, by offering a space where everyone is welcome, libraries also contribute to a sense of community – something that Sen and others have underlined as being a function of welfare systems more broadly.

Libraries are one of the few institutions in our societies which are genuinely open for all. This is something worth protecting, given the contribution this makes both to economic and social goals.

The emphasis in key IFLA texts – not least the Public Library Manifesto and the Statement on Libraries and Intellectual Freedom, which respectively turn 25 and 20 this year – on access for, and service to, all, are as relevant as ever.

Read further:

Cautherley, George (2016), Should Social Welfare be Universal or Means-Tested, in EJInsight, 18 April 2016, Accessible here: http://www.ejinsight.com/20160418-should-social-welfare-be-universal-or-means-tested/

Mkandwire, Thandika (2005), Targeting and Universalism in Developing Countries, United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/meetings/2005/docs/Mkandawire.pdf

Sen, Amartya (1995), The political economy of targeting, in Public spending and the poor: theory and evidence, edited by D. van de Walle & K. Nead (John Hopkins University Press, 1995), pp. 11-24. Accessible here: http://www.adatbank.ro/html/cim_pdf384.pdf

At two days to Human Rights Day 2018, the second-to-last of IFLA’s daily blogs looks at the right to participate in the cultural life of the community, or in short, the right to culture.

At two days to Human Rights Day 2018, the second-to-last of IFLA’s daily blogs looks at the right to participate in the cultural life of the community, or in short, the right to culture.