In our Library Stat of the Week mini-series on libraries and equality, we have looked so far at economic inequality, educational equality, and gender equality.

Through different blogs, we’ve explored the interaction between these and numbers of public and community libraries and librarians.

One factor which all too often correlates with poorer outcomes is immigrant status. In addition to difficulty in getting used to a new culture and language, or trying to get qualifications recognised, they can also face discrimination in different dimensions of life.

There are various ways in which libraries can help, from helping newcomers to feel at home and promoting tolerance and inclusion more broadly in society. A crucial way they can make a difference is by supporting literacy by helping newcomers.

To do this, we can use data from the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC), which assesses literacy, numeracy and problem-solving capabilities. In carrying this out, the OECD also collected data about whether respondents were native- or foreign-born, and whether they spoke the primary native or another language as a mother tongue.

We crossed this data with numbers of public and community libraries and librarians (and related staff) from IFLA’s Library Map of the World.

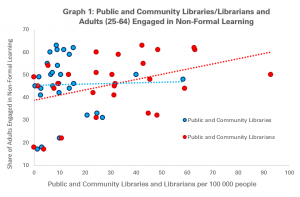

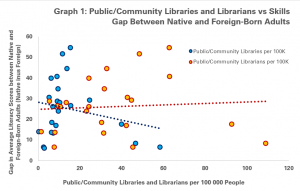

In a first step, we looked at the ‘gap’ between average literacy scores between native- and foreign-born adults, as shown in Graph 1.

Each dot represents a country for which data is available, with higher scores on the vertical (Y) axis indicating a wider gap (and so worse outcomes for foreign-born adults compared to native-born ones. Figures for the gap are adjusted to control for age, gender and educational level.

The results are relatively inconclusive, with little correlation between numbers of public and community libraries and library workers, and the gap.

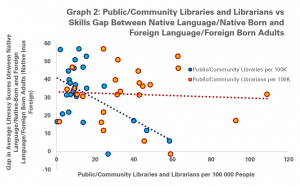

However, this is to forget that in many cases, a large share of immigrants come from countries where the native language is the same, or at least where the language of the welcoming country is common.

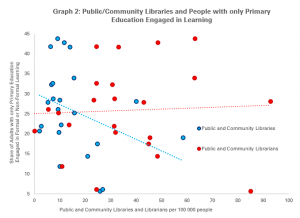

In Graph 2, we can address this by looking at the gap between native-born, native-language adults, and foreign-born, foreign-language adults. The difference is significant, with a much stronger correlation between greater numbers of public and community libraries and smaller gaps.

Indeed, for every 10 extra libraries per 100 000 people, the gap in literacy falls by 5.82 points on the PIAAC scale. There is a less obvious correlation with the number of librarians.

As is always noted in this series, there is a difference between correlation and causality, and this analysis does not make it possible to assess what other factors may be at play. As ever, more libraries (and librarians) may be a symptom of a society that has invested more in general in integration and inclusion.

It is nonetheless the case that where there are more public and community libraries, foreign-born, foreign-language migrants tend to face less of a disadvantage in literacy levels compared to native-born, native-language adults.

This could be explained by the possibility that libraries offer to develop language skills, either simply through access to books, or through programming (although the fact of no correlation with the number of librarians may weaken this point).

The fact of much weaker correlation in Graph 1 does at least underline that the potential of libraries as drivers of inclusion in general, beyond language, is not being realised. This is certainly an area where more can be done.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.