Digital vulnerabilities pose serious challenges for organisations, governments, companies and the wider public – libraries included. Cyberattacks and data breaches made headlines many times throughout 2019, from social media and popular software to public agencies. As a landmark 2019 report of the UN Secretary-General’s High-level Panel on Digital Cooperation pointed out, both the scope of threats and the range of targets for such attacks is rapidly growing.

For libraries, the importance of protecting the data and information they work with every day is readily apparent. Less than a week into 2020, the Contra Costa County Library in the US experienced a ransomware attack, impacting a number of library services.

From email scams to hacks into a library user database, library systems can become targets – and as the COVID-19 outbreak puts more pressure on online library resources, securing their digital assets and services, not least in order to protect staff and users, is a high priority. What is at stake, and what suggestions and tips for boosting libraries’ security can we draw from broader literature and available toolkits?

The Broader Context

Broadly in the field of security, you can think of three types of threats towards data: it can be lost, exposed, or made inaccessible (known as the CIA triad – confidentiality, integrity and accessibility). A poll among cybersecurity professionals, for example, shows that the three biggest expected threats in 2020 are “weaponized email attachments and links (74%), ransomware (71%), banking trojans and other browser-based password hijackers (67%)”.

An alternative top-level taxonomy of threats (borrowing from ENISA guidelines for a different sector) identifies: malicious actions (as described above), supply chain failure (e.g. cloud service provider failure), systems failure (e.g. software of device failure), as well as threats stemming from human errors or other phenomena. All, clearly, can have negative impacts.

On the positive side, however, public awareness on digital security and privacy matters has fundamentally shifted in the recent years, and more and more organisations and companies put a high priority on addressing these issues. In the UK alone, for example, about three-quarters of charities and businesses in 2019 reported that cybersecurity is a “high or very high priority”.

It is not just public attitudes that are changing. As the 2019 Internet and Jurisdiction report points out, security regulations are increasingly often linked to other fields of government regulation – especially data privacy. This can impact libraries: for instance, a 2019 publication by the Colorado State Library discussed how the recently introduced state regulation on personal information creates obligations for libraries to, inter alia, ‘implement reasonable security procedures and practices’. Similarly, under the EU GDPR libraries as data controllers have a responsibility to, inter alia, prevent, detect and report attacks and security breaches.

These regulations point to the fact that security concerns for libraries will always be particularly pressing when dealing with personally identifiable information (as well as, arguably, information on the habits and preferences of their users). So how to respond?

Assess and plan: key questions to ask

Map the assets, know the threats

A first key step to boosting a library’s cyber defence, as suggested in a number of recommendations and broader literature, is to take stock of your assets and digital systems. Map your entire system to see what needs to be protected: the Integrated Library System, the data you store, staff and patron computers, tablets and other devices, the library website, the network… Whenever applicable, this can also include apps and cloud services, since those can also contain vulnerabilities.

Once you know your assets, consider the vulnerabilities, priorities and risks. A toolkit published by Scottish PEN adapts an Electronic Frontier Foundation guide to highlight the key questions to consider:

- “What do you want to protect?”

- “Who do you want to protect it from?”

- “How likely is it that you will need to protect it?”

- “How bad are the consequences if you fail?”

- “How much trouble are you willing to go through in order to try to prevent those?”

You can also consider who has access to the assets you want to protect, and how you would know and respond if something goes wrong.

These questions can help you decide what measures to take to safeguard both privacy and security.

Setting up a plan

Having mapped the assets and considered the risks, you can develop a plan of security measures and risk mitigation strategies. Just like the assessment step, this is something to do together with your IT team – if your library has access to one! A 2019 Library Freedom Institute lecture on cybersecurity, for example, mentioned that some libraries might get IT support through their consortia or similar organisations, at a local City Hall, or elsewhere.

Your security plan and risk mitigation strategy would be built with your assets and situation in mind. Some key elements to consider when developing your security regime and policies are as follows – as set out in the Cyber Security Toolkit for Boards developed by the UK National Cyber Security Center:

- Network security

- User awareness and education

- Malware defense and prevention

- Access to removable media

- Maintaining the secure configuration of all systems

- Managing and limiting user privileges

- Incident management

- Monitoring

- Home and mobile working policy and security

Remembering the basics

Among these fundamental elements of the security regime, there are of course a few key concrete and tangible steps that can boost the security of your data, devices and processes. These are often mentioned when discussing the basics of cybersecurity, and you will likely have heard then often before:

- Creating backups of your systems is crucial! A library that experiences a ransomware attack, for example, could be able to restore their systems faster with the help of existing backups. Have a backup plan and system that fits your needs and capacities.

- Keeping your software updated, installing all patches and updates is a key security measure.

- Setting up a password policy. See, for instance, the Tactical Tech Data Detox Kit chapter on passwords to see what makes a good password (or better yet, a passphrase!)

- Website owners are encouraged to encrypt their website(s) and make use of HTTPS protocols instead of HTTP. HTTPS is a secure and encrypted protocol for communication between web browsers and websites – and the EFF offers some advice and resources for website owners on how to implement HTTPS by default. A 2018 case study of one public library’s HTTPS implementation points out that it is important to make use of HTPPS and related security measures consistently and pervasively, across all web-based library applications and their elements.

Staff training: protecting the library together

A key part of a library’s cyber defense – drawing on both broader literature and some library-focused overviews – is making sure that all your staff is caught up on the basics of online security. This can help make sure that the whole team is more alert and aware, reducing the likelihood of some of the most common threats like phishing or malware distributed through emails.

There are different resources available to start such training – such as those developed by the EFF. A 2019 pilot study published in Information Technology and Libraries, for example, provides initial evidence of how librarians taking part in online cybersecurity courses can utilise their knowledge to strengthen cybersecurity practices in their libraries.

Create learning opportunities for your communities

And finally, libraries can be well-positioned to help their community members learn essential skills to be safe online. There are different examples of how libraries have approached this task – from ad-hoc assistance or linking users to relevant educational materials, to dedicated workshops (see, for instance, a listing from the Tompkins County Public Library) or offering full courses on cyber-security (e.g. in the Hague Public Library).

Libraries can partner with cybersecurity specialists and agencies to deliver such training – as well as host dedicated awareness-raising campaigns. Depending on capacity, a library can adopt some of the approaches listed above- or find their own ways to help their communities with learn essential cybersecurity skills.

These are of course just a few broad elements highlighted in the broader literature to consider when creating a library’s security strategy. With more demand for online library resources and services – and so more risk – it is worthwhile to go over your library’s security plans and practices to be sure that your data, information and processes are safe and well!

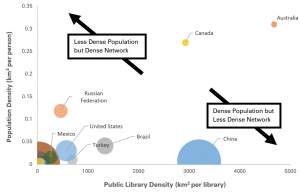

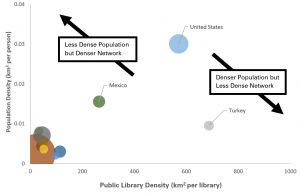

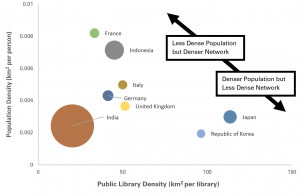

The next step is to look at the relationship between population density and library density.

The next step is to look at the relationship between population density and library density.

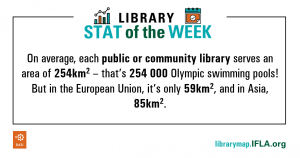

One of the key strengths of libraries – in particular public and community libraries – is the fact that they are local.

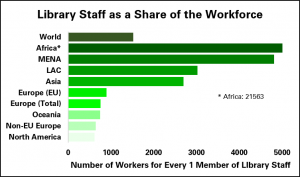

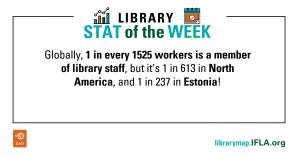

One of the key strengths of libraries – in particular public and community libraries – is the fact that they are local. Last week, we looked at the number of librarians for every 100 000 people around the world, with Oceania coming in highest at 84 – that’s one in every 1190 people.

Last week, we looked at the number of librarians for every 100 000 people around the world, with Oceania coming in highest at 84 – that’s one in every 1190 people.