The internet did not invent the spread of mis- and disinformation, but it has undoubtedly exploded the reach – and therefore, the impact – of harmful content. Every person with an internet connection can both fall victim to misinformation, and contribute to its creation and distribution.

It’s not all dire though! In the same way that misinformation can spread, so can opportunities for education and awareness-raising. Information can reach more people than ever before – but the type of information, and people’s skills to assess, understand, and ethically use it, will continue to have enormous consequences on peace, good governance, and social cohesion.

An Internet for Trust

UNESCO has been embarking on a process to develop global guidelines for the regulation of digital platforms. In this, UNESCO stresses that the development and implementation of digital platform regulatory processes must safeguard freedom of expression, access to information, and other human rights. IFLA has been contributing throughout this process – read our comments on the most recent draft here.

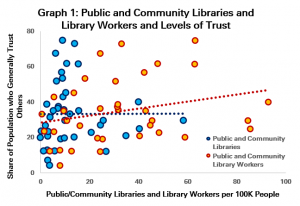

We stress that an internet for trust cannot be delivered in isolation, with action by platforms and through regulation legislation alone. Libraries contribute to building a healthier information ecosystem on a whole – an essential aspect of achieving the Guidelines’ goals.

A Healthy Information Ecosystem

UNESCO has linked Global Media and Information Week 2023 to their internet for trust initiative with this year’s theme: “Media and Information Literacy in Digital Spaces: A Collective Global Agenda”.

We were very happy to see the importance of media and information literacy (MIL) emphasised in preliminary drafts of the platform regulation guidelines. However, IFLA has called for stronger references to the role of libraries at all stages of planning and delivering MIL programming, and better coordination of platform-based efforts with those led by schools and libraries.

The idea of a collective global agenda is very much in line with IFLA’s point of view. It will take a lot of cooperation, and coordination of efforts, to build a healthy information ecosystem – but what does this mean in practice?

It means working at the grassroots level; it means policy supporting public sector actors in their work, it means MIL education that spans formal, informal, and non-formal spaces, and supports the development of global citizens enabled to act ethically in all aspects of their lives, with the specific skills needed to produce, access, and use information.

Progress will not be driven by platforms and policymakers alone, but by collaboration with a wider community of information holders, producers, and users.

Suggestions for Implementation

The fact that there is an international effort to guide the development of internet regulation is important, as inconsistencies in legislation from country to country could likely lead to further internet fragmentation.

This sort of coordinated effort on platform regulation could also result in coordination on MIL, given the strong emphasis on MIL in these Guidelines.

For Global MIL Week 2023, UNESCO asked IFLA, among other stakeholders, how the Guidelines for Regulating Digital Platforms could be made operational, and how we could ensure multistakeholder participation through this process.

From the perspective of the library and information profession, here are some thoughts for putting meaningful cooperation into practice:

- National and subnational policymakers should recognise the impact of public sector entities, such as libraries in communities, schools, and universities, for operationalising the guidelines through their role in building healthier information ecosystems.

- Libraries should be included in national policy efforts on MIL, supported by effective taxation that ensures resources are available for libraries to do their work.

- Teachers, trainers, and librarians should be provided with possibilities to access the skills, tools and resources they need to be effective, innovative, future-fit advocates and facilitators of media literacy.

- The youth should have an active role in contributing to change, but MIL education schemes should critically take a lifelong learning approach and include non-formal and informal education spaces.

- All stakeholders should recognise the importance of considering local language and local cultural context in efforts to vet content on platforms and ensure content is relevant and beneficial to users.

- Perceptions differ around where the greatest threat to freedom of expression and access to information lie. Information professionals could be included in digital platform regulatory processes for the expertise and values they can bring to wider discussions about equitable access to information and freedom of expression.

- Regulation applied to major commercial platforms, such as Facebook or YouTube, should not apply to the non-profit repositories run or used by any libraries, and which are essential for open access, science and education.

- Monitoring, evaluation, and reporting schemes at both the national and international levels should be designed with possibilities to include the contribution of civil society actors and public sector entities.

IFLA looks forward to seeing the final version of these Guidelines, hopefully with our previous input taken into consideration, and taking an active role in elaborating an implementation plan.

How do you see your role in contributing to an internet for trust through MIL? Let us know your thoughts!

Find out more about Global MIL Week and how to get involved here.