This is a guest blog by Adam Harangozó, a freelance creative worker.

Our past is crucial in understanding our present. It offers us knowledge and insights that help us to evaluate the world we live in today – the way we live our lives, structure our economies, and relate to each other and to nature. Learning from the past may yet help us correct mistakes and find better ways to live in the future. But for this to happen, there must be equal access to knowledge about the past, allowing for inclusive critical dialogue.

The Passenger Pigeon Manifesto (see below, and online),signed by a large number of professionals and cultural organisations, was born out of the fact that at a time of unprecedented species loss, the possibility for people to study animals that are no longer with us depends entirely on the accessibility of what has been written about them, or collected from them. With the 2nd Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biodiversity coming up next year, this is a crucial moment. There has rarely been a more appropriate time to talk about the importance of ensuring we can draw on this knowledge in order to understand how species decline, draw on insights that we can use more broadly in science, and simply raise awareness of what is at stake.

Clearly, loss of species is just one of many issues that ask us to re-evaluate our past. The COVID-19 pandemic, the climate crisis and Black Lives Matter all do so. In order to learn to do things differently, we must have free access to our past. There is also a growing readiness to look at what more can be done to make digitised collections available to all. The Passenger Pigeon Manifesto brings these issues together into a clear call for more work to make our heritage accessible for all.

Passenger Pigeon Manifesto

A call to public galleries, libraries, archives, and museums to liberate our cultural heritage. Illustrated with the cautionary tales of extinct species and our lack of access to what remains of them.

I.

How many people know about the passenger pigeons?

Martha, the last passenger pigeon to ever live on Earth, died on 1 September 1914. Less than 50 years before her, wild pigeons, as they were also called, flew in flocks of millions in the USA and Canada. Their numbers were so vast their arrival darkened the sky for hours, and branches of trees broke under the collective impact of their landing. Accounts describing how it felt to witness these birds were already unimaginable to most people at the beginning of the 20th century. Still, they are not a matter of poetry but factual natural history.

Simon Pokagon, a Native American Pottawatomi author and advocate, as a young man lived in a time when he could still see passenger pigeons “move in one unbroken column for hours across the sky, like some great river(…) from morning until night”. He noted that even though his tribe already named the birds O-me-me-wog, “why European race did not accept that name was, no doubt, because the bird so much resembled the domesticated pigeon; they naturally called it a wild pigeon, as they called us wild men”. Pokagon writes about witnessing a method of hunting passenger pigeons by feeding them whiskey-soaked mast, rendering them flightless. He was shattered by a tragic parallel: his tribe was devastated by the introduction of mass produced alcohol by white men.

Passenger pigeons mentioned in the Indiana State Sentinel newspaper. Public Domain. Source: Indiana State Sentinel/Wikimedia Commons https://bit.ly/2FySyuk

II.

The history of the passenger pigeons is accompanied by a ubiquitous disbelief. When the sight of millions was an integral part of the ecosystem and the everyday life of modern America, many did not believe a species of such numbers could go extinct. When their disappearance became an undeniable experience, people said they simply moved to South America. Today, chasing dreams of resurrection in the face of anthropogenic extinctions shows the still continuing failure to understand the finality of their death and come to terms with our responsibility.

Deep under all this, there is a tragic lack of self-reflection on what we, humans, are capable of. Many might try to dismiss this is as being only a matter of older times and societies long since transcended. Yet, there is no need to dig deep. Don’t forget about the widespread denial of climate change. Don’t forget about the anti-narratives to the Black Lives Matter movement claiming systematic racism does not exist, denying any connections to colonialism.

In order to improve, our definition of what it means to be human must include recognising the horrors we are capable of in societies of past and present. The systematic oppression of others and the massacre of billions of animals were done by human beings. Us. We can become better only if we realise that besides all the wonders, this is us too and it can happen again if we don’t change the ways we live together.

Thylacine at Beaumaris Zoo, 1936. Public Domain. Source: Ben Sheppard from Tasmanian Archives/Wikimedia Commons: https://bit.ly/35wsHhu

III.

A photo of one of the last thylacines, a species which became extinct when Benjamin died on 7 September 1936. Our imagination tries to grasp it through animals we know: it’s some kind of a tiger or a wolf. But it’s none of that, not even remotely related. What colours did it have? What did it sound like?

How do we feel when we look at photographs of animals long gone? Melancholy, the repressed fear of death, sorrow but also empathy, the desire to act – these are very important feelings. Black and white conveys a sadness of final loss that no colors can. Photography, no matter how deceptive it can be, is able to wash away cynicism and induce profoundly human emotions – ones we should feel when we think about injustice – human and non-human –, extinction or the climate crisis.

Looking at history provides a mental space where we can observe humanity and wonder about the whys and what ifs without the immediate frustration of the present. Exactly this removedness is what allows us to recognise and reflect on mistakes and right decisions.

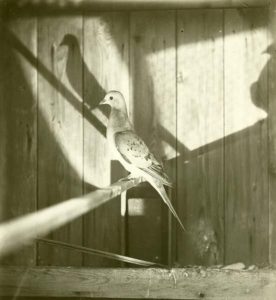

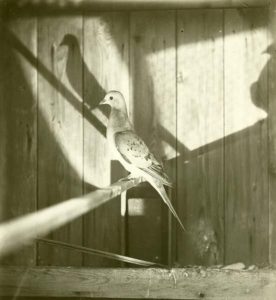

We are supposed to learn from history, yet we don’t have access to it. Historical photographs of extinct animals are among the most important artefacts to teach and inform about human impact on nature. But where to look when one wants to see all that is left of these beings? Where can we access all the extant photos of the thylacine or the passenger pigeon? History books use photos to help us relate to narratives and see a shared reality. But how can we look through our own communities’ photographic heritage, share it with each other and use it for research and education?

Historical photos are kept by archives, libraries, museums and other cultural institutions. Preservation, which is the goal of cultural institutions, means ensuring not only the existence of but the access to historical materials. It is the opposite of owning: it’s sustainable sharing. Similarly, conservation is not capturing and caging but ensuring the conditions and freedom to live.

Even though most of our tangible cultural heritage has not been digitised yet, a process greatly hindered by the lack of resources for professionals, we could already have much to look at online. In reality, a significant portion of already digitised historical photos is not available freely to the public – despite being in the public domain. We might be able to see thumbnails or medium sized previews scattered throughout numerous online catalogs but most of the time we don’t get to see them in full quality and detail. In general, they are hidden, the memory of their existence slowly going extinct.

The knowledge and efforts of these institutions are crucial in tending our cultural landscape but they cannot become prisons to our history. Instead of claiming ownership, their task is to provide unrestricted access and free use. Cultural heritage should not be accessible only for those who can afford paying for it.

V.

Acknowledging the importance of access to information and cultural heritage, and the vital role of public institutions, we call on galleries, libraries, archives, museums, zoos and historical societies all over the world:

1.) Cultural institutions should reflect on and rethink their roles in relation to access. While the current policy landscape, lack of infrastructure and the serious budget cuts do not support openness, cultural institutions cannot lose sight of their essential role in building bridges to culture. Preservation must mean ensuring our cultural heritage is always easily accessible to anyone. Without free, public access, these items will only be objects to be forgotten and rediscovered again and again, known only by exclusive communities.

2.) Physical preservation is not enough. Digital preservation of copies and metadata is essential but due to the erosion of storage, files can get damaged easily. To ensure the longevity of digital items, the existence of the highest possible number of copies is required: this can be achieved by sharing through free access.

3.) Beyond preservation and providing access, institutions need to communicate the existence and content of their collections, our cultural heritage. Even with unlimited access, not knowing about the existence and context of historical materials is almost the same as if they didn’t exist. Approachability and good communication is crucial in reaching people who otherwise have less access to knowledge.

4.) Publicly funded institutions must not be transformed by the market logic of neoliberalism. The role of archives, museums and other cultural institutions, is more and more challenged by capitalism. They need to redefine themselves in ways that allow cultural commodities to be archived, described and shared in the frameworks of open access and open science. The remedy to budget-cuts and marketisation requires wide-scale, public dialogue and collaboration. Involving people from outside of academia has great potential: NGOs, volunteers, open-source enthusiasts, online and offline communities and passionate individuals are a vast resource and should be encouraged to participate. Akin to citizen scientists, there can be citizen archivists.

5.) Liberate and upload all digitised photographs and artworks that are in the public domain or whose copyrights are owned by public institutions. Remove all restrictions on access, quality and reuse while applying cultural and ethical considerations (“open by default, closed by exception”). Prioritize adapting principles and values recommended by the OpenGLAM initiative in the upcoming ‘Declaration on Open Access for Cultural Heritage’.

6.) All collections should be searchable and accessible in an international, digital photo repository. Instead of spending on developing various new platforms for each institution, the ideal candidate for an independent, central imagebase that provides the widest possible reach is Wikimedia Commons. Using Commons would provide an immediate opportunity to release cultural heritage while still allowing the long-term development of digital archives for institutional purposes. Operated by the non-profit Wikimedia Foundation, Commons is a community managed, open and free multilanguage platform. It provides access to millions of people by sharing images under open licences. Wikipedias of all languages are using Commons to illustrate their articles, and the photos appear on news sites, blogs, and research articles all over the world. Wikimedia is open to collaboration with GLAMs and many institutions are already active on the site including the Digital Public Library of America and the Cultureel Erfgoed. By using Commons, institutions will also benefit: the platform runs on a free and flexible software where photos can be described and categorised using structured data. Utilising the participation of a large and diverse community in catalogising, tagging, publicising and even researching can save time and cut costs. At the same time, institutions will still retain the physical copies and will be able to use the digital photos on their own platforms as well. The images on Commons will also cite their original holding institutions, granting further visibility to their collections and efforts.

Today we are so far ahead in forgetting our past that we came very close to repeating it. Providing free, universal access to culture and knowledge is one of the steps we must take to prevent this.

Passenger Pigeon profile view with shadow. Public Domain. Source: J.G. Hubbard from Wisconsin Historical Society/Wikimedia Commons, https://bit.ly/3it0Xhx

A list of signatories is available on the Manifesto website: https://ppmanifesto.hcommons.org/