Discussion about questions of free speech and access to information is traditionally based around a divide between creators and users – or authors and readers in the case of books.

Discussion about questions of free speech and access to information is traditionally based around a divide between creators and users – or authors and readers in the case of books.

When something goes wrong – an author goes beyond the limits of acceptable free speech or plagiarises, or a reader pirates a work – it makes it easy to ascribe blame.

Of course, there have long been many other players in the chain, helping works get from the one to the other, from publishers or record companies to distributors, bookstores and libraries. These are essential as connectors between authors and readers. Without them, there is no connection, no exchange.

All of these actors are, in principle, established in order to promote and make legitimate uses of works. Of course, they may risk making mistakes – it is clear that the boundaries of fair uses of works, as well as of free speech, are unclear.

This makes it more difficult to establish what happens when something goes wrong. To what extent should those through whose hands a work has passed be held responsible for the acts of others? What should they do when mistakes happen?

It seems appropriate that these actors should enjoy the benefit of the doubt. A publisher – who of course knows a book inside out – should not be prosecuted when a book they publish can legitimately be seen as free speech.

Libraries and bookstores, which will have an idea of their stock without necessarily having been able to read everything, should be held to a lower standard. If they act in good faith, and act rapidly when due process leads to the conclusion that a mistake has been made, should also not be held accountable.

And of course distributors, who cannot be expected to read the content that sits in the back of the van, should logically be exempt.

This is, in effect, the concept of safe harbour. It ensures that actors which are essential to making the connection between writer and reader are able to use their skills and best judgement in order to go about their jobs.

They can take risks, and thanks to this, innovate and bring new ideas and services which benefit society as a whole. Crucially, one mistake should not come at the expense of all of the legitimate services and support provided.

New Actors, Old Issue?

The internet adds a new element to this – the wires, servers, hosting services, and platforms that have massively facilitated the distribution of books, articles, and other works.

Again, with some limited exceptions, these are established in order to promote and facilitate legitimate uses. They often serve other purposes too, such as communication as well as the personal sharing of original works.

They have become as essential to the connection between creators and readers as the delivery van once was (and of course still is in some markets). For libraries also, maximum access to information over the internet is a key means of providing services.

So what to do when something goes wrong? When someone writes something dangerous or unjustifiably discriminatory? When a reader makes an illegitimate copy of a work, or access something illegal?

The concept that emerged with the WIPO Copyright Treaty of 1996 was the same safe harbour. The idea that when someone acts in good faith, and acts rapidly when a mistake is pointed out, then they should not be held fully responsible.

The standard varies from service to service. Just as it varies between publishers and delivery vans, the same goes with the difference between the editors of news sites or blogs and the hosting services or internet service providers, or the many other actors involved in getting information from keyboard to screen (including, in the case of library computers, the screens themselves!).

While technical tools exist that can indicate potentially illegal activity, these cannot be relied upon, with growing evidence (here, here, here) of automatic filters creating havoc with legitimate speech.

However, there is increasing pressure to restrict the idea of safe harbour and create liability (for copyright infringement, dangerous content etc).

This is driven in part by a frustration at the fact that finding, catching and prosecuting the person or organisation at the origin of the illegal behaviour can be difficult. Unlike platforms, ISPs or libraries, they may not have a clear physical address and legal existence.

In part, it doubtless also comes from the fact that some of these intermediaries have grown very rich, or enjoy a position in the market that allows them to dictate terms, more or less, to others.

Neither of these arguments, though, justify an attack on the concept of safe harbour itself. This is all the more so given that such restrictions risk not only hurting commercial platforms, but also other actors such as Wikipedia, libraries and others.

Trying to draw a line between platforms that benefit and platforms that don’t is fraught with difficulty. It brings the risk that all platforms and services will feel the need to implement more restrictive policies that will hurt most innovators and risk takers.

Libraries therefore have a major interest in protecting safe harbour if they are to be able to fulfil their missions – both inside their walls and on the wider internet.

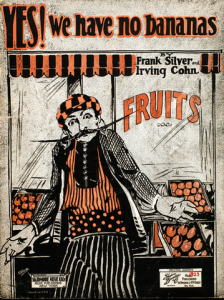

1 January 2019 saw a greater than usual focus on the importance of the public domain. For the first time in 20 years, new works started to go out of copyright in the United States, following a 20 year hiatus.

1 January 2019 saw a greater than usual focus on the importance of the public domain. For the first time in 20 years, new works started to go out of copyright in the United States, following a 20 year hiatus. Libraries, the Commons, and the Not-100%-Private

Libraries, the Commons, and the Not-100%-Private