1 January of each year is Public Domain Day, the day that a new set of historical works enter the public domain, opening up wide new possibilities for access and use.

The reason for this all happening on 1 January is because many copyright laws provide protection for a set number of years (at minimum 50, often more) after the end of the year in which the creator died.

This protection gives an exclusive right to control things like reproduction, distribution, translation, performance, or communicating to the public online. These tend to be known as ‘economic’ rights; meanwhile ‘moral’ rights (such as to be named alongside a work) do not have a limit in time.

As such, in countries with protection lasting for life plus 50 years, it means that the works of creators who died in 1971 are now far more freely available. In countries with protection lasting for life plus 70 years, it is the works of creators who died in 1951. Some other countries have more complex rules – you can find out more on the relevant Wikipedia page.

While of course it may seem odd to be celebrating the fact that a certain time has passed since a death, in reality, entry into the public domain brings many benefits, including of course to creators insofar as their original motivation for creating will have been to share their ideas with the world.

Nonetheless, there is an unfortunate trend towards trying to extend copyright terms, often as part of trade deals, limiting when new books, songs and images enter into the public domain. There are also efforts in some countries to charge fees for use of public domain works, or at least direct reproductions of them.

This blog sets out three connected angles to the argument for celebrating Public Domain Day.

Library collections liberated

Public Domain Day is an important moment for libraries holding works whose economic copyright protection comes to an end.

To survive until this point, relevant books, documents, recordings, images, and other materials will likely have benefitted from significant investment in preservation and conservation.

And while they may well have been open for limited access and use already, entry into the public domain is what creates many new opportunities to ensure an impact in terms of access to and use of works.

For example, new possibilities emerge to make digital copies of works which can be made freely available online, to use copies in class or even research, in person or remotely without payment, and library users have much wider options to play with or remix works.

In effect, it allows for a much deeper, richer engagement between library users and the heritage and ideas of the past, going beyond the simple ‘consumption’ of works.

Clearly, in providing access, it remains important to remember that copyright is not the only factor at play in deciding whether to provide access to works or not. Factors such as the interests and preferences of indigenous groups, privacy and beyond will also come into play!

Building the knowledge commons

Connected to the previous point is about what entry into the public domain means for the ability of libraries to make an impact, a second argument focuses on how this contributes to the building of the Knowledge Commons.

This is a term that has existed for a while already, building on previous ideas of ‘commons’ – things and resources that are owned by, and available, to all, contributing to individual and collective wellbeing.

It receives particular attention in the recent UNESCO Futures of Education report, which refers to it as ‘the collective knowledge resources of humanity that have been accumulated over generations and are continuously transforming’.

The UNESCO report underlines how important it is for young people, as they learn, to be able not only to access this commons, but also to contribute to it. It cites this as a step away from rote-learning, with young people simply forced to accept the status quo.

Clearly, possibilities for access, analysis, and re-use are at their strongest when works are in the public domain! In effect, each year on 1 January, we can mark the moment that the knowledge commons grows stronger, offering new possibilities for learning, sharing and creativity.

Maximising welfare

Of course, a key argument for copyright in the first place is that it is by keeping works out of the public domain, and so crating artificial scarcity, that it is possible to generate the income necessary to cover the costs of creation.

While of course it is unsurprising that actors depending on a business model built on the exploitation of copyright will tend to paint this as the only possible means of supporting creativity, it is also true that no other dominant single dominant model has yet emerged to replace it, at least in the creative industries. Clearly we do have an interest in ensuring that those who have a talent for developing and expressing new ideas should have a means of earning a living by doing it.

The question then is where to find the balance. One way of thinking about this is by looking at costs and benefits over time.

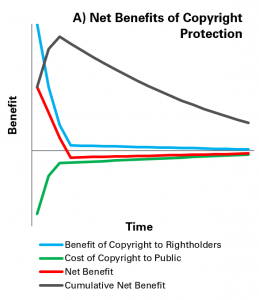

Graph A offers a way of reflecting on this, for a complete set of works published in a given year. The horizontal axis represents time after publication, and the vertical, benefits/costs. Figures are not included, as the graph provides a model, rather than a set calculation, and because it can be hard to put a clear figure on monetary costs or benefits to some things.

Graph A offers a way of reflecting on this, for a complete set of works published in a given year. The horizontal axis represents time after publication, and the vertical, benefits/costs. Figures are not included, as the graph provides a model, rather than a set calculation, and because it can be hard to put a clear figure on monetary costs or benefits to some things.

The blue line represents the benefit to rightholders from copyright – in effect what is earned from sales and other licensing revenue. This starts high, but rapidly falls, with a ‘long tail’. This reflects the fact that most copyrighted works have a very limited commercial life, and just a few will continue to make money for a long time while others are effectively forgotten or worse, lost.

The green line represents the costs to the public – the impact of people who would benefit from having access to the full set of works not having it, for example to support education, research or wellbeing. Clearly some people can buy works, but it’s assumed that they have paid what they felt the work was worth, and so there is no net cost or benefit to them.

The red line therefore represents the net benefit of copyright to society as a whole – i.e. the benefit to the rightholder minus the cost to the public.

At first, this is positive. However, after a time, the cost to the public of not being able to access works becomes greater than sales or licensing fees for rightholders. At this point, the red line drops below the axis, representing a net loss to society as a whole.

Finally, the dark grey line represents the cumulative net benefit over time. At first, this is growing. However, once the costs of copyright grow higher than the benefits, this line starts falling, representing a falling total benefit to society over time.

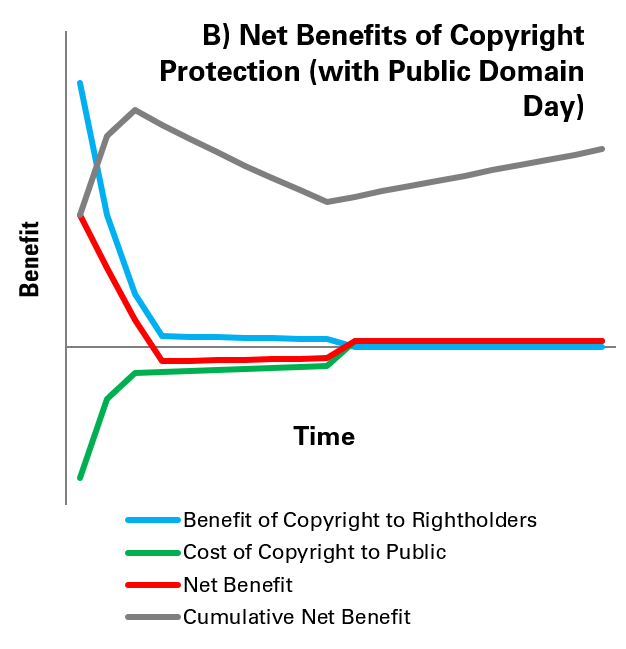

Entry into the public domain provides a response to this situation of a falling cumulative net benefit over time. Graph B illustrates this. At halfway along the horizontal axis, works from a given year enter the public domain, and so benefits to rightholders from sales and licensing fees (blue line), which were already low and falling, are reduced to zero. However, the costs to the public (green line) also disappear, and in fact turn into benefits as people are able to use and enjoy works freely.

Entry into the public domain provides a response to this situation of a falling cumulative net benefit over time. Graph B illustrates this. At halfway along the horizontal axis, works from a given year enter the public domain, and so benefits to rightholders from sales and licensing fees (blue line), which were already low and falling, are reduced to zero. However, the costs to the public (green line) also disappear, and in fact turn into benefits as people are able to use and enjoy works freely.

The impact of this is that there is now a net benefit to society again (red line), meaning that cumulative net benefits (grey line) also start to rise again, reversing the downward trend previously seen.

Of course, the specific shape of some of these lines can be discussed (and of course, date of entry into the public domain most often depends on when the author dies), but in effect, this provides a more economic model for understanding why the public domain matters for the societies that libraries serve.

In particular, assuming that the term of copyright protection is already longer than the point at which the costs of copyright start to outweigh the benefits, then any extension of terms would certainly lead to further net losses to society.

In summary, public domain day is something to be celebrated, both for libraries themselves, and for the societies we serve. It creates new possibilities for libraries to get the best out of their collections, it significantly expands the knowledge commons, and it corrects a situation of falling net benefits to society.

Happy Public Domain Day!

Interested in finding out more? Key organisations associated with the public domain are holding a celebration on 20 January, with a particular emphasis on the sound recordings now becoming available – find out more here!