The COVID-19 Pandemic has both underlined the importance of access to information, and how far we are from achieving this for all.

From the need for rapid access to research to inform policy making, to the development of media and information literacy skills amongst individuals in the face of misinformation, the need for comprehensive policies on information is clear.

Yet at the same time, with so many parts of our societies and economies moving online, the costs of being unable to access and use information easily have been made clear.

This comes as much through the months of schooling lost for those unable to take part in distance learning or work and do business online, as through the and isolation stress felt by those unable to communicate with their friends and families, or access culture online.

These are of course key issues for libraries too, as key pillars of the infrastructure for access to information in any country, and so for the delivery of this right.

While of course the spread of internet has created exciting possibilities to access information directly, libraries contribute in three essential ways: helping to ensure that those without an internet connection can get online, helping to ensure that works which are otherwise protected or restricted (for example by copyright) are still accessible, and helping to ensure that users have the skills and confidence to be successful information users.

The Pandemic has disrupted all of these, and with it the right of access to information. If we are to be better prepared in the future to ensure the continued enjoyment of this right, there are a number of steps we can take.

All represent good risk-management practice, by removing unnecessary uncertainties in the ability of libraries to respond. All work to ensure that access to information should be protected, and enacted, as a right, rather than seen as a gift or a privilege.

Towards Universal Connectivity: the goal of ensuring universal internet access is not a new one, with public access in libraries cited already in the WSIS Agenda of 2003 as a means of doing this. Technologies such as WiFi and models such as community networks offer promising means of bringing library connectivity out to communities – an essential step if libraries are forced to suspend in-person services again.

Achieving this will certainly require investment, and in many cases regulatory change, but would certainly bring returns in terms of higher uptake of services (such as education, eHealth and similar), create new business opportunities, and fulfil what is increasingly being seen as a moral obligation on governments to treat internet access as a basic utility like water or electricity.

Copyright Fit for the Digital Age: the failure of copyright laws to adapt to the digital age in many countries has meant that libraries have been unable to carry out online many of the services they would have offered in person. Physical collections were stuck behind library doors, with little possibility to provide digital access, for example through sharing scanned copies. Storytimes that previously took place in the library could not, in many cases, be done online.

Fortunately, this was not the case everywhere. In many cases, there have been welcome moves by publishers, distributors and others to allow for access – many are detailed on the page hosting the ICOLC Statement on the Global COVID-19 Pandemic and its Impact on Library Services and Resources. Others – including agreements between publishers and library associations to allow for storytimes – are noted on IFLA’s COVID-19 and Libraries page.

However, it is arguable that where libraries have already been given the possibility to offer a service to users in person – through an exception or limitation to copyright – they should be able to count on being able to do the same online, in as similar a way as possible. In other words, having already paid for a work, the possibility to allow users to access it digitally should not be a gift depending on the goodwill of the rightholder, but rather a legal certainty.

This can be guaranteed through using secure networks, and tools to prevent simultaneous uses. Achieving this will require copyright laws to be updated, notably to make it clear that digital uses are permitted, and to ensure that they cannot be taken away by contract terms, as is currently typically the case. Further help would come from deeper understanding of the pricing and availability of electronic resources for libraries.

A Digitally Enabled Population: finally, with it clear that skills and confidence play a major role in whether people make use of the possibilities that exist to access information, there is a need to have a greater focus on promoting digital and information skills, at all ages.

Clearly with the Pandemic, the potential for libraries to offer in-person support has been limited. Yet libraries have sought to be in touch with users by phone and other means, and provide guidance and support, as well as developing tailored tutorials to help people develop digital skills. In the longer term, what seems necessary is a more comprehensive approach to developing digital skills in the population, with libraries as key delivery partners within this, as some are already doing.

While many elements of this may require in-person support – and so will need to wait for the Pandemic to have receded – others can already be scaled-up in order to do the best possible in the months and years to come.

With the recognition of the International Day for the Universal Access to Information by the UN General Assembly as a full UN-level observance, there is a new opportunity to raise awareness of the steps needed to make this right a reality for all, whatever the circumstances.

Meaningful plans to ensure internet connections, digital access to library collections, and the skills needed to make the most of both, can all help ensure that when the next crisis hits – and even before – access to information is a right, rather than just a privilege or a gift.

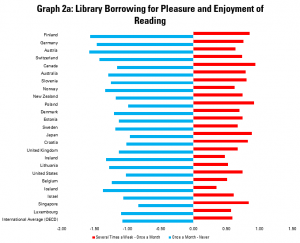

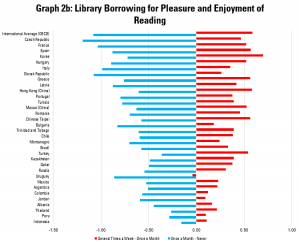

These graphs indicate levels of enjoyment of reading amongst 15-year olds who borrow books only once a month, compared to those who do so never, and those who do so several times a week.

These graphs indicate levels of enjoyment of reading amongst 15-year olds who borrow books only once a month, compared to those who do so never, and those who do so several times a week.

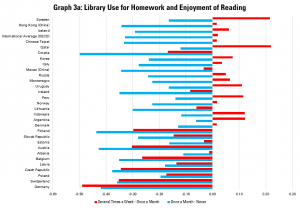

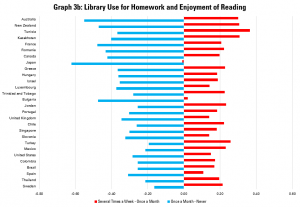

Graphs 3a and 3b look at the links between levels of enjoyment of reading and how often students use the library to carry out homework.

Graphs 3a and 3b look at the links between levels of enjoyment of reading and how often students use the library to carry out homework.

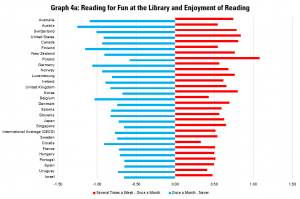

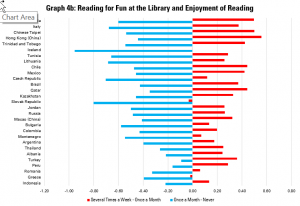

Finally, graphs 4a and 4b look at the links between enjoyment of reading and using the library to read for fun. Again, it is expected that more regular reading for fun at the library is linked to greater enjoyment of reading in general.

Finally, graphs 4a and 4b look at the links between enjoyment of reading and using the library to read for fun. Again, it is expected that more regular reading for fun at the library is linked to greater enjoyment of reading in general.