After a few weeks of focusing on public and community libraries, it’s time to take a look, instead, at academic libraries. These are at the heart of the institutions they serve, as well as core parts of the infrastructure of any country for learning and research.

While future posts will look at the relationship between academic libraries and library workers and various indicators of research and education outputs, this week we’ll be looking just at how many institutions and staff there are, both in absolute terms, and related to population (using World Bank data for 2018).

Overall, globally, IFLA’s Library Map of the World counts over 80 000 academic libraries globally, on the basis of data from 105 countries, representing a total population of over 6bn (almost 80% of the total).

The largest number of academic libraries is in India, with over 42 000 alone recorded there, followed by the United States (4266) and China (almost 3000). In other world regions, Nigeria has the most in Africa (815), Ukraine in Eurasia (1843), Italy in Europe (1581), Brazil in Latin America and the Caribbean (2407), Egypt the most in the Middle East and North Africa (464), and Australia the most in Oceania (190).

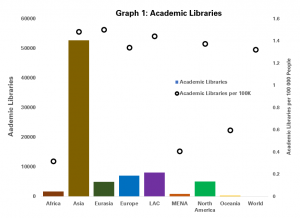

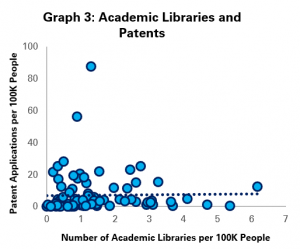

Graph 1 provides further insights into number of academic libraries per region (where India ensures that Asia comes out as having the highest number of academic libraries, but also offers figures relative to population sizes.

This helps us see that globally, there are 1.32 academic libraries per 100 000 people, although at a regional level, this varies from over 1.5 in North America to 0.31 in Africa and 0.41 in the Middle East and North Africa.

The variation is wider still at the national level, going from 6.17 academic libraries per 100 000 people in Slovenia, followed by Kiribati (6.04), Macao, China (5.38) and Argentina (4.71) to 0.004 in Madagascar. It is of course possible that there is under-reporting here.

Other regional leaders include Benin in Africa (1.87 academic libraries per 100 000 people), Ukraine in Eurasia (4.13), Bahrain in MENA (1.02), and Canada in North America (1.98).

However, as has also been underlined in the case of public libraries, staff are essential. Without them, students and researchers cannot benefit from the expertise and advice that trained librarians can bring, and the library cannot fulfil its potential.

Globally, the Library Map of the World suggests that there are almost 350 000 academic library workers, although in this case only from 78 countries’ data (accounting for 43% of the world population).

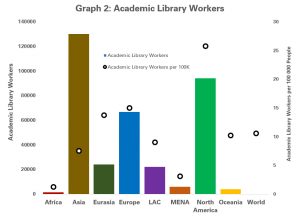

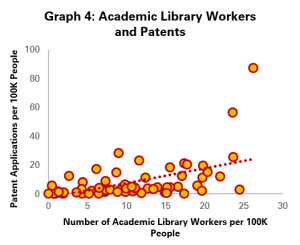

Graph 2 goes into more depth, breaking down numbers of academic library workers per region, and relative to overall population sizes. Once again, Asia comes out on top in terms of numbers of workers at almost 130 000 (not including India this time), with North America a little way behind on 93909.

Graph 2 goes into more depth, breaking down numbers of academic library workers per region, and relative to overall population sizes. Once again, Asia comes out on top in terms of numbers of workers at almost 130 000 (not including India this time), with North America a little way behind on 93909.

At the national level, China has the largest single number of academic librarians (111023), followed by the United States (85752). Regional leaders (for which data is available) are Zimbabwe for Africa (750), Kazakhstan for Eurasia (10000), Germany for Europe (19614), Mexico for Latin America and the Caribbean (11209), Egypt for MENA (4309) and Australia for Oceania (3116).

Once again, it is interesting to look at numbers of library workers in relation to the population as a whole. Globally, there appear to be 10.63 academic library workers per 100 000 people (where data is available), with North America coming top at 25.8, and Europe some way behind at 15.02. Africa stands at 1.26 and MENA at 3.13.

At the national level, variation is wider still, going from 54.72 academic library workers per 100 000 in Kazakhstan and 26.25 in the United States to 0.07 in Uganda and 0.17 in Papua New Guinea. It is again possible that there is under-reporting here.

Other regional leaders in terms of numbers of academic library workers per 100 000 people are Mauritius in Africa (9.88), Brunei in Asia (19.12), Lithuania in Europe (24.52), Colombia in Latin America and the Caribbean (15.23), Egypt in MENA (4.38) and New Zealand in Oceania (17.43).

These figures both provide an interesting insight into the state of academic libraries around the world, but also provide a starting point for further analysis of how the strength of the academic library field might relate to other outcomes.

Clearly, we are still working with incomplete figures and so numbers need to be used with some caution, but it is already powerful to be able to start to explore these themes.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.

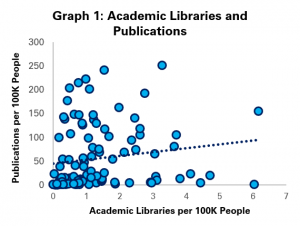

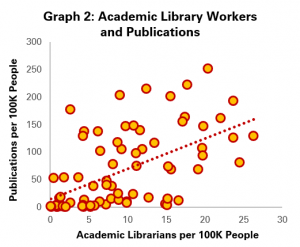

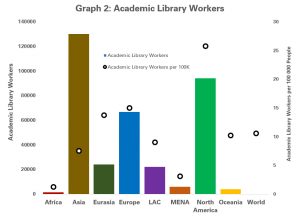

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1).

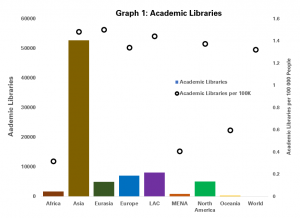

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1). Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people.

Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people. Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

Graph 2 goes into more depth, breaking down numbers of academic library workers per region, and relative to overall population sizes. Once again, Asia comes out on top in terms of numbers of workers at almost 130 000 (not including India this time), with North America a little way behind on 93909.

Graph 2 goes into more depth, breaking down numbers of academic library workers per region, and relative to overall population sizes. Once again, Asia comes out on top in terms of numbers of workers at almost 130 000 (not including India this time), with North America a little way behind on 93909.