The Gates Foundation’s Goalkeepers 2020 report, published earlier this week, highlights the risk that literacy could suffer as a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

It presents different projections, suggesting that the share of children finishing primary school with the ability to read and understand a basic text could fall back to 2015, or even 2010 levels.

This has important knock-on effects, with children then struggling to engage with other subjects at school, achieving less, and finding it harder to integrate into the labour market later in life.

A key determinant of literacy, as underlined in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is enjoyment of reading outside of school. In turn, a key argument made in library advocacy is that our institutions – both public, and embedded in schools, can help build a love of reading.

There have been a good number of studies exploring the connection between school libraries and reading performance at the local level. But what does the data say at the global level?

To explore this, we have brought together information from the IFLA Library Map of the World, as well as OECD PISA data, which used surveys of students alongside tests to find out about habits related to reading.

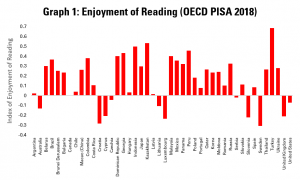

Graph 1, as a first step, looks at average levels of enjoyment of reading among 15 year olds in participating countries, based on data for 2018. The higher (more positive) a bar is, the more children in the country, on average, report enjoying reading.

This underlines strong variation between countries, with 15 year olds in Turkey, Kazakhstan, Peru and Indonesia displaying the highest level of enjoyment of reading, while those in Denmark, Croatia and Sweden were less keen.

It is worth noting that total figures, as displayed here, cover varying levels of enjoyment within populations (and indeed, it is on this basis that the OECD can show links between enjoyment and literacy).

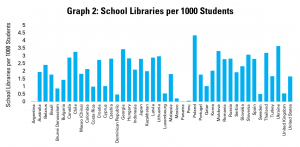

Graph 2 turns to the number of school libraries per student. Combining UNESCO Institute for Statistics data with that from the IFLA Library Map of the World data, we can work out how many school libraries there are for every 1000 children enrolled in primary or secondary schools.

For countries for which we have data, there are an average of 1.81 school libraries per 1000 students. Within this, there is strong variation, with the largest number of school libraries per student being found in Poland, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.

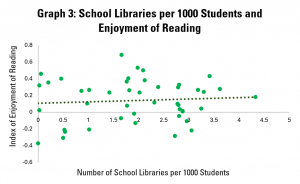

Graph 3 brings this data together, with numbers of school libraries per 1000 students on the horizontal (X) axis, and the enjoyment of reading index on the vertical (y) axis.

This indicates a positive correlation between numbers of school libraries and enjoyment of reading, demonstrated by the gently rising line. This indicates that in general, where there are more school libraries, enjoyment of reading.

Clearly, however, there are limitations to this finding. First of all, not all countries operate with school libraries, with public libraries taking up their role. And of course, having more school libraries may be part of a wider strategy to promote reading, including through different techniques for promoting this.

They may also organise schools differently, with larger or smaller institutions, which will affect the number of libraries per student. Finally, data on school library workers is limited, meaning that is it not possible to carry out analysis using this.

Future editions of Library Stat of the Week will dig deeper into the available data on school (and public) libraries, and results from OECD’s work on reading habits and performance among children.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.