January 2 was Public Domain Day in 2023, celebrating the works that now belong to the ages (and you!). Public domain works may be copied from, remixed, incorporated into other works and generally utilized for free, without payment to rightsholders. They are viewed as part of the commons from which the world draws to make new art and knowledge. This often takes effect between 50 and 80 years after the death of the author (70 years in most countries). To find out whose work enters the public domain in 2023 in your country, Wikipedia has a useful chart.

January 2 was Public Domain Day in 2023, celebrating the works that now belong to the ages (and you!). Public domain works may be copied from, remixed, incorporated into other works and generally utilized for free, without payment to rightsholders. They are viewed as part of the commons from which the world draws to make new art and knowledge. This often takes effect between 50 and 80 years after the death of the author (70 years in most countries). To find out whose work enters the public domain in 2023 in your country, Wikipedia has a useful chart.

Our blog post from last year details some implications for libraries – including greater opportunities for digitising material in collections and building our shared ‘knowledge commons’, as well as charts detailing the benefits of public domain to the social good, by making works accessible after their (often relatively short) commercial life wanes.

While the fate of most works is obscurity as they fall out of print, the public domain offers a chance for revitalised distribution. Nonetheless, many works remain influential. Many blogs have detailed all the works you’re now able to use, and we recommend looking at them. For some highlights (leaning heavily on film, where my greatest interest falls):

- Wings (1927), the first movie to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, which features aerial battle action and this impressive tracking shot in a café that occasionally makes the rounds on social media. Still on my to-watch list, and this will be a good excuse!

- The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes, the last remaining collection of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories (written 1923-7) that was not already in the public domain. Speaking to the ridiculousness of holding onto copyright ownership for a character so diffused in the public imagination, in 2020 Doyle’s estate sued Netflix over a film adaptation on the logic that the character had not displayed empathy in earlier stories and therefore any story in which Holmes was not emotionally detached was still under copyright as an adaptation of the later stories. The suit was dismissed.

- Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), a beautiful silent era classic from Germany, which finished at #11 this November on Sight and Sound’s once-in-a-decade poll of the best films of all time.

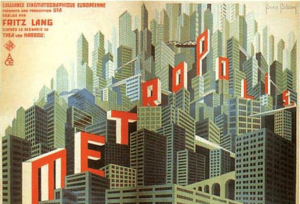

- Metropolis (1927), one of the most influential science fiction films of all time and a personal favorite, a key focus point for imagery of mad scientists, cyborgs, and dystopic cities. Here’s a good two-part blog on the film from earlier this year, noting particularly that “Most science fiction builds the future on the foundation of the present — Metropolis is, if not unique, then close to it in extending that foundation into the distant past. Rotwang lives in a house ‘forgotten for centuries’ where he works with an unholy fusion of science and black magic: note the ever-present pentagrams and the alchemical device sitting in his wood stove. The climax takes place in a Gothic cathedral.”

Metropolis in particular is, in its own way, an argument for the value of the public domain, with its vision of a future built on ‘foundations in the past’, as well as its long history of indirect adaptation (while plenty of films were influenced by it, the city of Blade Runner often looks like a more detailed copy of Metropolis’ metropolis) and direct (a stage musical, Giorgio Moroder’s version with an alternate 80s soundtrack) and versions of multiple length for the film itself owing to scenes lost during edits made during its early international circulation. Key, plot-relevant scenes long thought lost were rediscovered in 2008 in the Museo del Cine Pablo Ducrós Hicken in Buenos Aires.

While the lost Metropolis scenes were considered a ‘Holy Grail’ level find of the silent era, the film was able to find influence without them. It still existed! An estimated total of just 25% of (American) films of the silent era remain in any known, accessible format at all (though some artists have made interesting attempts at resurrections, including imagining what those films might contain based solely on their titles). Films of the era weren’t preserved when their commercial lives were thought over. Clearly, a system relying on studios alone, which follow a market logic, to ensure the survival of these works has failed.

The above works have stood the test of time to be recognizable and influential today. They are now available to be shared, adapted, and further distributed more freely. They officially belong to a world that had long since claimed them. However, most works in the public domain are considerably more obscure. Who knows what gems are hiding now that they are liberated for further use?

We need institutions like libraries and archives to provide a guarantee of preservation of the works that shape our world – something that over-extended copyright adds to the difficulties of.

So as you enjoy the new possibilities that Public Domain Day brings to enjoy the works of the past, remember also all the hard work by libraries that and others that have helped them survive, and reflect on what we can do to ensure that we safeguard the films and other materials of today for the future.

Happy discovery in 2023!

A version of this post also appears on IFLA News.

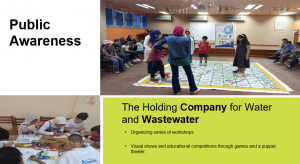

Misr Public Library System (MPL) in cooperation with the Faculty of Early Childhood Education, Cairo University, which is concerned with educating ordinary children and people with special needs, launched an initiative entitled “Towards a promising environmentally friendly childhood.” The initiative includes several activities and events:

Misr Public Library System (MPL) in cooperation with the Faculty of Early Childhood Education, Cairo University, which is concerned with educating ordinary children and people with special needs, launched an initiative entitled “Towards a promising environmentally friendly childhood.” The initiative includes several activities and events:

The BA Sustainable Development Studies, Youth Capacity Building, and African Relations Support Program organized “Alexandria Climathon for Youth” competition. “Climathon” is an international competition held in several countries around the world through EIT Climate-KIC, which aims at raising the awareness of urban residents about climate changes. The competition is an opportunity for young people to participate in developing ideas that address local climate challenges. The activities of “Climathon” are held internationally on the same date in hundreds of cities, and are supported by local organizers.

The BA Sustainable Development Studies, Youth Capacity Building, and African Relations Support Program organized “Alexandria Climathon for Youth” competition. “Climathon” is an international competition held in several countries around the world through EIT Climate-KIC, which aims at raising the awareness of urban residents about climate changes. The competition is an opportunity for young people to participate in developing ideas that address local climate challenges. The activities of “Climathon” are held internationally on the same date in hundreds of cities, and are supported by local organizers.