IFLA’s Regional Advocacy Priorities Study was designed in order to start conversations about where we focus in our advocacy, and how we do it.

It is intended, in particular, to stimulate reflection about the focus of coordinated, national-level efforts, such as those carried out by associations, and of course about how IFLA and its different structures can support them.

This reflection is worthwhile. While IFLA underlines strongly that advocacy is something that individuals can do without needing extensive training or to dedicate a huge amount of time to, it is clear that full campaigns or other efforts to change policies and laws do require investment of effort.

We need to make sure we’re picking impactful areas on which to focus, and then mobilising the energy of library and information workers and supporters!

Determining what these areas are can depend on a number of factors.

A first is simply how big an issue is in general. It’s obviously difficult to mobilise efforts anyway around an issue that really isn’t particularly important, but also, if a change in law or policy isn’t going to have a major impact, it may not deserve much energy.

A second is what impact libraries can expect to have. This is perhaps more important even than the first factor. It can be easy to want to act on every issue that hits the headlines, but we need to be realistic about whether there is a ‘library angle’, and so whether libraries getting involved could make a difference.

A third is whether you have the ability to take the steps needed to make a difference. There may be many important issues where, with unlimited resources, libraries could effect change across the field. However, this is not the case for any of us, and so choices need to be made.

In the Library Advocacy Priorities Study, we therefore asked respondents to indicate which broad policy issues they felt mattered most as areas of focus for library advocacy.

We picked the below – these are of course just one way of ‘cutting the cake’, and if you want to reproduce this exercise in your own association or institution, you may want to do it differently. You may want more detail on some issues, or group other issues together. You could also use the division of policies among ministries in your government, or other structures!

Library laws: this refers to legislation setting out the status, rights, and responsibilities of libraries at a high level. Such laws can in particular establish obligations on governments at different levels to set up libraries, and the services they should offer.

Library staff: this refers to laws and policies concerning library staff, including qualifications. This is a recurrent question in many countries, where there can be pressures to remove qualification requirements for certain posts, or a shortage of qualified librarians.

Copyright and OA: this refers to laws and policies around copyright and open access. Such laws can either enable, restrict or create uncertainty around what libraries are able to do with their collections. They can also include rules obliging open access publication of research results and data, or funding for it.

Literacy and Reading: this refers to laws, policies, and strategies concerning literacy and reading promotion. Some countries also have strategies for promoting books, which can include libraries too of course.

Education and lifelong learning: this refers to laws policies, and strategies for learning, in particular adult learning. Libraries are often active skills providers, as well as being gateways towards more formal offerings.

Digital inclusion and connectivity: this refers to laws, policies, and strategies focused on ensuring that everyone can get online and make the most of the internet. It includes work on connectivity, but also skills and arguably content, plus the rules by which the internet itself operates.

Heritage and culture: this refers to laws, policies, and strategies around preservation of and access to heritage and support for contemporary culture and creativity. It can cover funding for this work too, and of course efforts to ensure that libraries are seen as an essential cultural infrastructure.

Legal deposit: this refers to the policies and laws that give deposit libraries (often national libraries) the right to receive copies of a range of works, in different formats, including for example to creation national bibliographies, or simply to maintain the historical record.

Social inclusion: this refers to policies and strategies for tackling inequalities and exclusion, for example to support potentially marginalised groups to participate and fulfil their potential. It can also, potentially, extend to wider efforts to promote social cohesion.

Division of responsibility: this refers to efforts to ensure that the division of responsibility for libraries between levels of government works in a way that best enables our institutions

So what did we find in terms of where priorities lay, bearing in mind that the number of responses (around 400) is far from enough to allow for any definitive conclusions?

Here are three initial ideas:

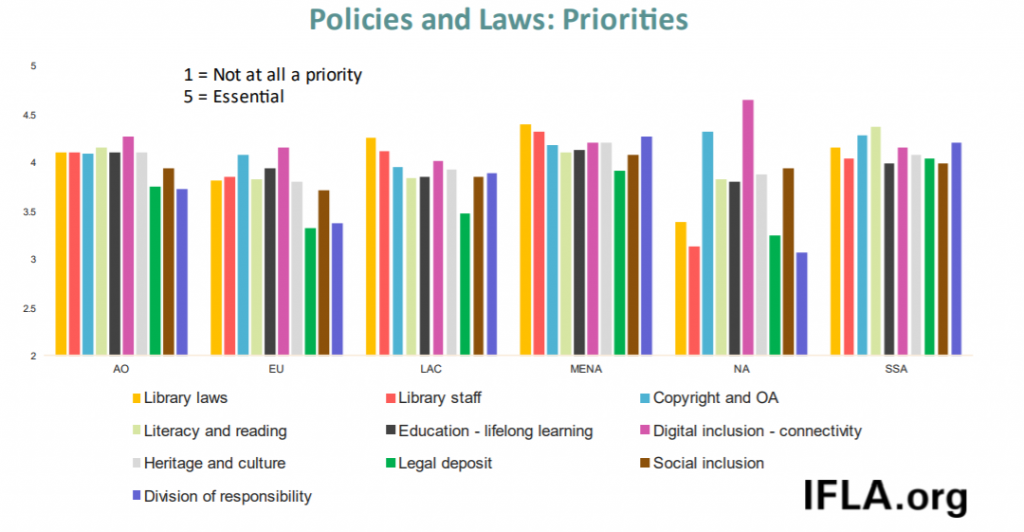

Does overall level of development correlate with the policy focus of library advocacy?: an initial thing that stands out from the results for all respondents (see p37 of the report), are the difference between richer regions, and those with a higher share of developing states.

The three regions with generally higher incomes (North America, Europe, and Asia-Oceania, or at least East Asia and the Pacific) placed digital inclusion first on their list of priorities. This makes sense, in the light of an increasing focus on digital inclusion as a key for delivering wider policy goals, such as combatting inequalities.

Indeed, as these countries move to do more and more using digital tools (education, health, eGovernment), the need to find solutions to engage people who are unconnected grows (as the pandemic has illustrated). In addition, with many of these countries also risking losing some lower skilled jobs to foreign competition, the need to get more people into higher-skilled, digital work grows.

Engagement in such programmes can of course be associated with greater funding and support for libraries.

The two ‘middling’ regions – Latin America and the Caribbean and the Middle East and North Africa focus rather on library laws, policies and staff. This may reflect a need to ensure that libraries are able to fulfil more fundamental roles, and concern about funding in general. Indeed, governments in these region may face budgetary pressures that can lead them to under-fund libraries.

In this situation, it makes sense to focus first of all on how to ensure that libraries have a strong starting point, and then only later look to branch out to other policy areas where there may be possibilities to secure funding that complements core budgets.

Finally, Sub-Saharan Africa places literacy and reading first. With almost 40% of the population counted as illiterate, it is logical that libraries would see this as a key area of focus, not least given that a more literate population potentially also of course increases demand for and interest in libraries. At the same time, literacy and reading policies can serve to increase the profile of libraries, and provide them with the funding needed to operate.

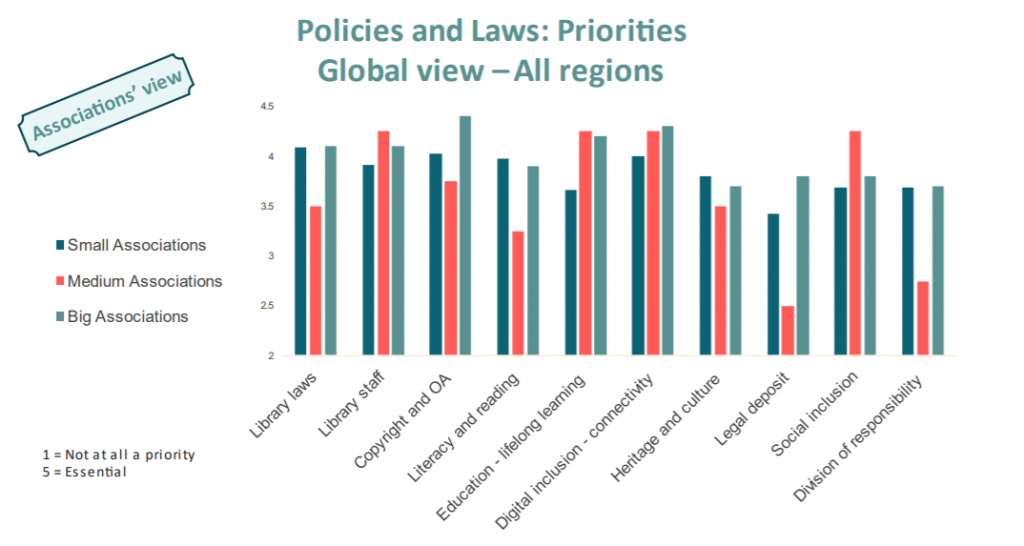

The size of associations may be linked to different areas of focus: the study made sure to ask respondents whether they were answering on behalf of associations, institutions or just themselves, and what size of association or institution they represented.

The logic here was in line with the third reflection above – do you have the capacity to make a difference. Smaller, general associations could be less focused on more ‘technical’ issues, and find it easier to engage more general efforts to ensure that libraries are properly supported.

The logic here was in line with the third reflection above – do you have the capacity to make a difference. Smaller, general associations could be less focused on more ‘technical’ issues, and find it easier to engage more general efforts to ensure that libraries are properly supported.

The results do seem to vindicate this assumption to some extent. For smaller associations, the highest scoring policy area was library laws, which can be seen as a more general topic (or at least one where there may not be so much need to develop technical expertise), although this is followed by copyright and digital inclusion. Copyright tends to be a more technical area, while advocacy around digital inclusion can stretch from general calls for support to more technical elements, such as setting up programmes, engaging around internet regulation and beyond).

Meanwhile, larger associations themselves place copyright first, perhaps reflecting the fact that they are better placed to develop specific expertise. Digital inclusion comes next, and then education and lifelong learning. As above advocacy around digital inclusion can be both general and technical – the same arguably goes for education as well.

In particular in Europe (p49), the picture is clearer still – small associations focus on library laws and staffing most, while larger ones see copyright, digital inclusion, and education and lifelong learning as most essential.

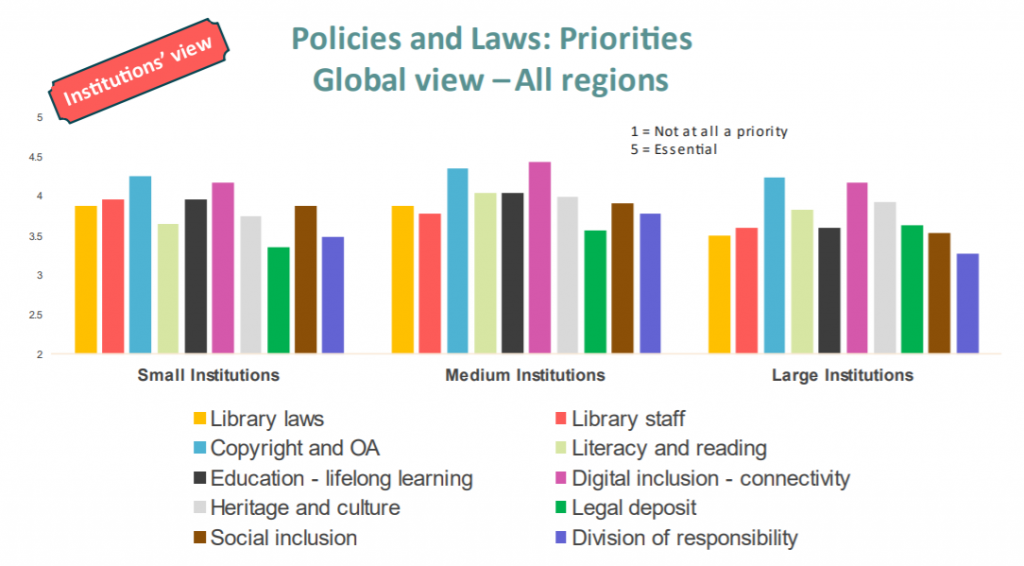

Institutions globally tend to focus on copyright and digital inclusion: looking at the global level across the issues that matter most for institutions (p52), regardless of size, copyright and open access, and digital inclusion come out on top. This makes sense, given the impact that policies in these areas can have on the daily operation of institutions, determining the programmes they can run, and what they can do with their collections.

Larger institutions place heritage and culture in third place, while medium-sized ones look at education and literacy, and smaller ones give a bigger role to library laws and staffing.

Larger institutions place heritage and culture in third place, while medium-sized ones look at education and literacy, and smaller ones give a bigger role to library laws and staffing.

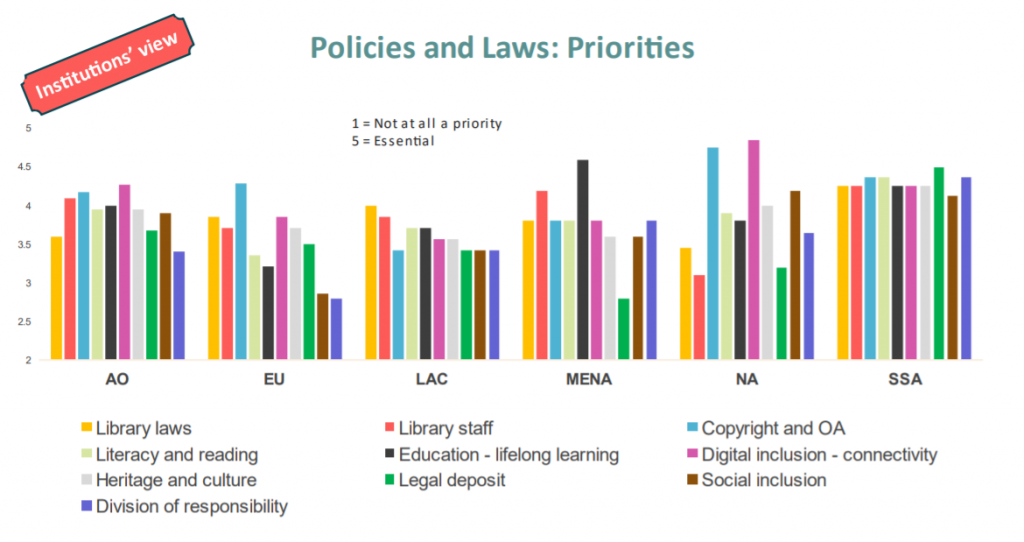

Breaking this down regionally, a different picture emerges though. In Asia-Oceania, Europe and North America, it is again copyright and digital inclusion that come first. However in Sub-Saharan Africa, legal deposit is the priority (it is possible that a large share of respondents were national libraries for example), while in the Middle East and North Africa, education and lifelong learning comes top, followed by library staffing. This may reflect a priority on enabling school and academic libraries to thrive.

Breaking this down regionally, a different picture emerges though. In Asia-Oceania, Europe and North America, it is again copyright and digital inclusion that come first. However in Sub-Saharan Africa, legal deposit is the priority (it is possible that a large share of respondents were national libraries for example), while in the Middle East and North Africa, education and lifelong learning comes top, followed by library staffing. This may reflect a priority on enabling school and academic libraries to thrive.

Finally, Latin America and the Caribbean institutions again see library laws and staffing as being most important, mirroring the results for all respondents in the region (set out above).

In terms of the issues that come third, interesting features include the high result for social inclusion among North American institutions, and for divisions of responsibility for libraries between levels of government in Sub-Saharan Africa. Literacy also features in the top four or five response in all regions except Europe.

Watch out next week for an analysis of the results about advocacy activities!