When COVID-19 began sweeping the world in the early months of 2020, public life made a collective retreat indoors. Schools closed, museums shuttered, and many libraries had no choice but to halt in-person services for their communities. On our COVID-19 and the Global Library Field page, IFLA has made an effort to aggregate methods by which libraries have been able to offer services remotely during full or partial closures.

However, for libraries holding cultural heritage collections, engagement becomes more complex.

For collection-holding memory institutions, connecting people to cultural resources is central to the institution’s mission. For years now, the importance of online presence and social media has driven memory institutions to rethink access beyond physical visits. In 2020, lock-down measures have accelerated this need for innovative approaches to access and engagement.

The reality of online engagement is here to stay, during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the world that follows. How do you start building a community around your digital collections, especially if your institution is new to this?

Human-centred Digital Engagement

The collections held in Oxford University’s libraries and museums play a major role in the university’s engagement with their academic community and society at large. For that reason, engaging visitors through digital means is a top priority in the University’s Digital Strategy.

Oxford therefore designed their Engagement Strategy with a human-centred approach. In short, this means first establishing the types of visitors to their memory institutions, then designing the rest of the digital engagement strategy to address their individual wants and needs.

Oxford University did this by identifying Audience Architypes – subsets of users that have similar traits, needs, and expectations in common. This could be “university students” or “parents with young children” – it depends on the type of library and collections you have.

Ask: If you had to reduce your collections’ audience to broad subsets of users, who might these be? What types of people may fall into each subset? Why do they visit your institution? How do they use your collections?

Finally, how do you offer a similar experience to these audiences by digital means?

In this article, we will explore several audience architypes that may be applicable to collection-holding institutions. We will then share some examples of how other libraries are engaging with each of these groups digitally.

The Deep-Divers

They engage with a mission – they know what they are looking for and will explore a subject in depth.

Who they may be: secondary school students, undergraduates, graduate students and researchers, journalists, other members of an academic community.

Why they might visit: to access information relevant to their study, for reference help, to further their research and find new leads.

What they might value: archives, online catalogues, access to academic journals, reference and research assistance

How they might find you online: this group is likely to be familiar with your institution, or with other institutions in your network. They probably come directly to your website looking for specific information.

These audience members are most likely already interacting with your institution. The best way to engage them could therefore be to ensure adequate digitisation and access to your collections’ materials, and to provide research assistance – both in-person and virtually.

See this example from the University of Sao Paolo, Brazil, and their Digital Library of Rare, Special Works and Historical Documentation. This is a result of cooperation between multiple national digitisation initiatives, bringing digitised collections together in one place, free of charge to researchers and the public.

Another example comes from Leiden University’s Digital Collections. Members of the academic community and beyond can engage through online access to digitised and digital born collections, contextualisation through regular blog posts, and services allowing for the digitisation and reuse of materials for research or publication.

The Explorers

They browse multiple topics that interest them, reaching the history behind the headlines, or hunting for interesting glimpses at the past worth sharing.

Who they might be: members of the general public, travel-lovers, current or past students, art-enthusiasts, museum-goers, history buffs.

Why they might visit: they are somehow aware of your institution and collections, they value your authority on topics that interest them, they are interested in adding historical context to issues they care about.

What they might value: blog articles, social media posts, thought-pieces, curated collections, contextual analysis, topics relating to social commentary and current events, content that is shareable.

How they might find you online: this group might have visited your institution in the past, liked what they saw, and followed you on social media. Or, they might have seen someone in their network share your content and wanted to explore more. Perhaps they came across your institution in a blog article, news piece, or other online channel.

The United States-based Amistad Research Centre library and archive holds a vast collection of materials of social and cultural importance regarding America’s ethnic and racial history.

In addition to organising site-based exhibitions, the Research Centre makes use of the Google Arts & Culture platform to deliver online exhibitions. This platform allows for the institution to feature images and videos from its collection, together with text to give context and enrich audiences’ understanding. Their online exhibitions are great examples of using this platform. Check it out here.

Conversations in Color, a video series on topics relating to race in America, builds on the material collection further by engaging experts and promoting dialogue.

The Bibliothèque Forney, based in Paris, France, has found great success engaging audiences with their collection on social media. During the pandemic, staff has had more time to write articles sharing stories and celebrating pieces from their collections. This has enriched their social media presence, and the library has reported thousands of users on their channels (Facebook, Twitter and Instagram).

Collections which have been particularly appreciated for their aesthetic beauty and public interest include commercial catalogues for toys and classic department stores, posters, fashion periodicals, and wallpapers.

Their Facebook page is a great example of curating an aesthetic that resonates with its audience. Check it out here.

Denmark’s Herlev Bibliotek takes curating an aesthetic even further on their beautiful Instagram page. Perhaps this excellent use of a visual platform can be inspiration for featuring your collection on social media?

The Action-takers

They are looking to be inspired or looking for tools to inspire others. They may be interested in interactive activities and opportunities to get involved in crowd-sourced activities.

Who they might be: artists (professional or hobby), art-lovers, social media creators, students out of school, teachers, parents with young and adolescent children.

Why they might visit: they have free time and an interest in creative pursuits. Or they might be looking for ways to enrich and entertain children, as a teacher or parent/caregiver.

What they might value: interactive projects, open-source material, recognition and sharing opportunities, creative inspiration and prompts, insight from specialists on early childhood education and arts education.

How they might find you online: Similarly to the Explorers, this group could engage with you primarily through social media. Perhaps they were involved with an in-person event your institution ran in the past. Or maybe they see others in their network participating in similar projects, and are keen to be involved too.

Also from Leiden University, a very successful project in drawing in members of the public was the Maps in the Crowd project. It invited anyone with interest to get involved in their geocrowdsourcing project, connecting old maps from their Special Collection with their modern-day locations. Special prizes helped incentivise and recognise participation.

A great example of engaging a different creative audience is the British Library’s Discovering Children’s Books online project.

This project is rich with interactive, multimedia features to deepen engagement with children’s books, like videos depicting illustrators drawing their well-known characters, arts and crafts ideas, and guided activities, such as inspiring children to write their own stories.

Conclusions

Alongside the many challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic has brought, there are also opportunities to enhance the way your audience engages with your collections.

In speaking with the Bibliothèque Forney, they said that online engagement during the pandemic, especially on social media channels, has showed that “even if [the library] was ‘dematerialized’, it could still exist and maintain a true dialogue with its public.”

There are many more ways than we listed here to maintain this dialogue. For instance, Europeana has collected more ideas for digital engagement in this article. Many are targeted at museums, but they could certainly be adapted to collections-holding libraries as well. Stay creative and look for inspiration everywhere.

By establishing your visitors’ individuality at the centre of your digital engagement strategy and keeping an open mind towards ways to connect, your collections can have a much further reach than ever before.

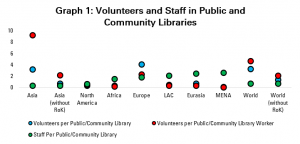

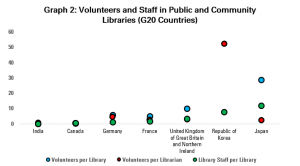

Graph 2 presents data for those larger (G20) economies for which data is available. Among these countries, it is relatively common to have more volunteers than FTE staff, with Germany, France, the UK and Japan in this situation.

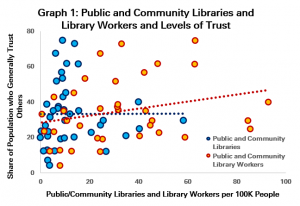

Graph 2 presents data for those larger (G20) economies for which data is available. Among these countries, it is relatively common to have more volunteers than FTE staff, with Germany, France, the UK and Japan in this situation. Graph 1 compares numbers of libraries and library workers (on the horizontal X-axis) with the share of the population who felt that other people could be trusted. Each dot represents one country.

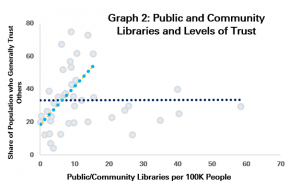

Graph 1 compares numbers of libraries and library workers (on the horizontal X-axis) with the share of the population who felt that other people could be trusted. Each dot represents one country. Graph 2 looks further into this question, including a trend line only for countries with fewer than 20 libraries per 100 000 people (i.e. one library per 5000 people).

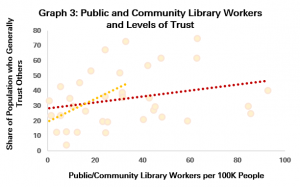

Graph 2 looks further into this question, including a trend line only for countries with fewer than 20 libraries per 100 000 people (i.e. one library per 5000 people). Graph 3 repeats the same process for countries with up to 40 public and community library workers per 100 000 people (the yellow line), coming to a similar conclusion. The relationship between library workers and trust is much stronger among countries below the threshold of 40 workers per 100K.

Graph 3 repeats the same process for countries with up to 40 public and community library workers per 100 000 people (the yellow line), coming to a similar conclusion. The relationship between library workers and trust is much stronger among countries below the threshold of 40 workers per 100K.