Two weeks ago, we looked at data on adult literacy levels from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competences (PIAAC), in order to explore the potential relationship with the coverage of public and community libraries in countries.

In that post, we explored the numbers of adults scoring at or below a basic level of skills, as well as the gap between the most and least literate in a population.

However, PIAAC, data also allows us to break things down further, including by gender. This has been a particularly interesting area of study, given that while girls tend to score better on literacy at school (as demonstrated by the results of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)), they too often face disadvantage on the job market.

One argument noted by the OECD itself is that the jobs that women tend to be encouraged to take up make fewer demands of their skills, and so there is less opportunity to develop these. This is clearly not an ideal situation, given the implication both that women have fewer chances to learn throughout life, but also the loss this represents to societies and economies as a whole.

As has been highlighted in each Library Stat of the Week post focused on skills issues, public and community libraries do have an important role both in helping to maintain literacy skills (through access to materials and activities), but also in providing a second chance for those who have done less well in school.

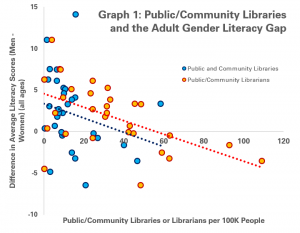

This week’s post therefore looks to compare OECD data about adult gender literacy gaps (calculated by subtracting the mean literacy score of women from that of men – a negative result means that the average women has higher skills than the average man) and numbers of public and community libraries and librarians per 100 000 people from the IFLA Library Map of the World.

It is worth noting that the data here comes primarily from OECD Member States, with each of the dots in the graphs below representing a country.

In Graph 1, we look at data for adults of all ages surveyed (15-65). When looking both at numbers of public and community libraries and librarians, there is correlation, with more libraries/librarians tending to mean that women on average have higher literacy skills than men.

The correlation is stronger when looking at librarians as opposed to libraries – an observation that has also appeared in previous blogs.

As ever, correlation does not always mean causality. In particular, the size of gender gaps above may be influenced by investment in high-quality and inclusive schools (something which is also likely to correlate with investment in libraries).

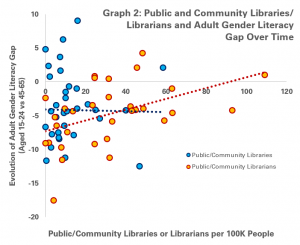

A next step then is to look at differences over time, given that the advantage that may come from high-quality education will diminish over time, and other factors – such as the presence of public and community libraries – will count for more.

Graph 2 does this by looking at the evolution of the adult gender literacy gap between 15-24 year olds and 45-65 year olds.

On the vertical axis, a score above zero indicates that the gap between men and women is more favourable to women among 45-65 year olds than among 15-24 year olds, whereas a score below zero implies a wider gap among older than among younger adults.

The graph suggests that there is a positive correlation between numbers of public and community library workers per 100 000 people and stability or improvement in the adult gender literacy gap over time.

Clearly, as ever, there can be other explanations – countries which have seen improvements in the gender gap (in favour of women) may also have a range of policies in place that support life-long learning, and a more equitable employment situation for women.

Nonetheless, the correlation is a welcome support for efforts to ensure that libraries are a part of any government strategy to promote gender equality.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.