In 2019, the United Nations will launch a review of the whole 2030 Agenda. While it is still unclear where the focus of this will be, it’s a useful opportunity to look back across the Sustainable Development Goals, and the process in place for monitoring their implementation.

What’s clear is the progress that the Agenda has brought. On 25 September 2015, governments agreed to taking a truly holistic approach to development. They recognised that progress in any one area is dependent on progress elsewhere, and that there are cross-cutting themes.

The implication is that governments need to be thinking about certain issues across their work. In effect, these need to be ‘mainstreamed’ – taken into account in everything else they do.

Such themes include questions like equality or sustainability. To give the example of education, governments should be thinking about how to ensure that all children have access to quality schooling, regardless of their background. They should be teaching children about how to live sustainably, and giving them the skills to get ‘green’ jobs in future.

Access is Everywhere…

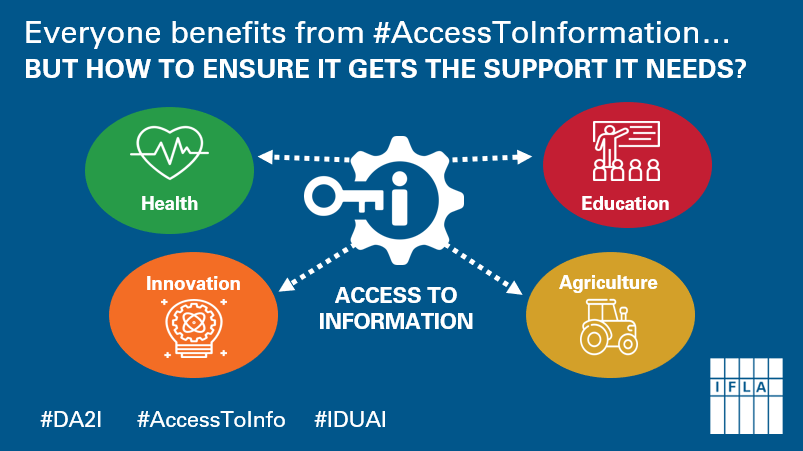

Access to information is another key example of a theme that needs to be taken into account across the work of governments. It is not only included explicitly in SDG 16.10, but appears in nearly 20 other SDG targets. Indeed, there are few policy areas where access to information does not contribute to equity and effectiveness.

To take just a few examples, SDG 2.3 underlines the need for small farmers to have access to knowledge, while 2c calls for access to market information. In other words, we will only get to ‘zero hunger’ with access to information.

Under SDG3 (good health and wellbeing), target 3.4 mentions the need to prevent disease (in which information is essential), and 3.7 clearly talks about the need for information and education around reproductive health.

Target 5b stresses that women need to be able to access and use information technologies, and target 13.3 places an emphasis on education and awareness raising around climate change.

As IFLA has underlined a number of times, this represents an affirmation of libraries, and of the meaningful access to information that they provide. By offering a welcoming, public space, with dedicated staff and access to resources, libraries are an ideal tool for achieving progress across the board.

With access to information mainstreamed across the Agenda, libraries truly are partners for development. The Development and Access to Information report, produced by IFLA in partnership with the Technology and Social Change Group at the University of Washington, offers further examples.

But Risks Being No-Where

Yet mainstreaming comes with challenges, not least in the case of access to information.

Because when everyone benefits, no single ministry or agency takes responsibility for it. There is no single source of funding to make sure it happens.

It risks being seen as a secondary priority compared to other things, less urgent, less necessary.

This can be a problem in the case of libraries, which need adequate support to be able to function effectively. Almost all ministries in governments benefit from their work – education, health, agriculture, economy, innovation, and of course culture – but it is often only one that carries the costs of running them.

This creates a collective action problem, where the fact that the costs and benefits do not fall in the same place may mean that a policy or institution – in this case access to information and libraries – do not receive the funding they need.

To some extent, local governments – which often have responsibilities across a number of policy areas – are able to solve this. Yet even there, it is often agencies and ministries at the national or regional level who will get the credit for improvements in health or employment, for example.

Without a strong central commitment, or strong coordination, library funding, and so access to information, is at risk.

Much of IFLA’s advocacy around access to information – at all levels – aims to ensure that governments at all levels recognise the value of libraries and the access they provide, and give this the support they need.

This support should come from all parts of government that benefit. It may be fantasy to expect that governments should pool resources dedicated to access to information in order to support libraries. However, we should expect political and moral support at least.

IFLA’s advocacy, both at the national and the global levels, is there to remind them.

The European Parliament’s vote on the draft copyright directive next Wednesday is likely to be the last chance for transparent discussion on the substance of a reform that has been years in the making. It is also a last chance for libraries to reach out to and influence Members of the European Parliament.

The European Parliament’s vote on the draft copyright directive next Wednesday is likely to be the last chance for transparent discussion on the substance of a reform that has been years in the making. It is also a last chance for libraries to reach out to and influence Members of the European Parliament.