This blog post aims to give prospective Standing Committee members the opportunity to experience – through words – a “day in the life” of an IFLA Section officer. I hope to answer some common questions, including what an IFLA Section officer “feels like” and what an Information Coordinator deals with at work.

As the Information Coordinator of this Section, I thought it was valuable to share what has shaped my work as an officer for my Section.

Time spent

I spend an average of about 5-10 hours per month as an Information Coordinator. It will vary accordingly, depending on the specific projects you take on as a standing committee member. This translates to about 1-2 hours per week. Most of my time is spent communicating on emails and updating our Basecamp, webpages, blog, and repository. It is more of a sprint rather than a regular block of time, dealing with projects and other matters as they come up.

Being a global library or information worker colleague

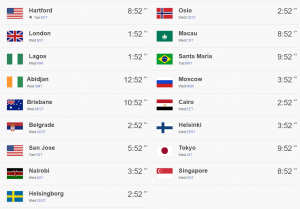

The Event Time Announcer tool on timeanddate.com has become my default go-to whenever we discuss upcoming events (meetings, webinars, etc.). Like many other IFLA sections, our Section has a standing committee with members from more than 10 countries and time zones. Sharing the web address will ensure that no one is confused about what time it is for them.

I want to acknowledge that there is no magic date or date, as our colleagues operate in different environments and time zones. It is essential to accommodate various parties and interests and be flexible. We want to always give the benefit of the doubt to a colleague who cannot attend, will be late, or needs to leave early. Value good note-taking over recordings because we do not have time to sit through recordings even on 2X playback.

Cultural intelligence helps to build and maintain relationships

How do we communicate and listen effectively across cultures? Erin Meyer has developed a short, 25-part questionnaire that you can answer to learn more about your cultural profile. She is a professor at INSEAD, an expert in cross-cultural management, and the author of The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business. The last question of her questionnaire is on your nationality (or where you were raised). I have met many colleagues with IFLA that have a different workplace from their nationality, including myself.

A graph depicting how confrontational and emotionally expressive people with a certain nationalities can be. Source: Erin Meyer.

Navigating the social media landscape of China can be tricky, similar to keeping up with the developments of Instagram and TikTok in other parts of the world. I am often quizzed about how to reach out to Chinese librarians and librarians working in the Asia Pacific, even as I am no longer working in that part of the world. (I can speak and read Mandarin and identify as ethnically Chinese, even though I belong to the vast, diverse, overseas Chinese diaspora.)

The million-dollar question: how do we adapt to our colleagues’ cultural preferences, lead across cultures, and create an accommodating, safe team culture? My response is the standard textbook answer. Be explicit with your team norms, be ready to explain the reasoning behind them, and acknowledge how it might feel outside one’s socially acceptable behavior.

Censorship, freedom of access, and freedom of expression

Censorship is an excellent example, especially relevant in our profession. Our Section has an explicit norm of not censoring others in their communications, exemplified in our blog posts. This may feel uncomfortable for me, growing up in Singapore, in a culture of self-censorship and mindful of what I say on specific topics involving politics and personal values. We have an exchange of perspectives, not to persuade others to our point of view, but to learn and acknowledge.

Working with international colleagues will require one to acknowledge different interpretations of what is universally accepted. For example, as librarians, we embrace one of IFLA’s core values of “the endorsement of the principles of freedom of access to information, ideas and works of imagination and freedom of expression embodied in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”. Start a conversation about book censorship with the American librarians, and you will hear a different story from the European librarians.

Why getting names right matters

No name is common or “normative” in a global community. Consider sharing the pronunciation of your name using apps like Namedrop and NameCoach. If Zoom or the video conferencing platform allows you to use the original characters of your name, be proud of it. Others on the call might develop an interest or ask you about the significance of your name. I remain fascinated with the meaning behind names from languages unfamiliar to me.

I admit that I constantly mispronounce the names of my collaborators, especially with my European colleagues and friends. They are most understanding, and in return, I empathize with their attempts to get Asian names right.

Like any community, it is the collective experiences and expertise that we are better off together. There will be misunderstandings and apologies, which are part of learning and growing together. As an Information Coordinator, I keep it short and straightforward and leave time for stories and others to join our conversations.