Author: Roxanne Missingham, University Librarian, Australian National University

Introduction

Academic libraries are fundamental supporters of research activities in their institutions. The digital environment has opened up the collections and services so that they sit within reach in every lab and researchers’ desktop as a part of the research toolkit that supports research in every discipline. The extensive connection with researchers has provided the opportunity to engage with this community to implement many new services to meet their needs.

At the Australian National University, a member of the International Alliance of Research Universities, the Dean of Science commented some years ago that he visited the digital library every day, relying more than ever on the full range of library services. For those in the humanities and social sciences the library is perceived as their laboratory, the research infrastructure on which their work depends. Professor Frank Bongiorno recently stated, “For historians, libraries and archives are the laboratory” (Bongiorno, 2022). This provides an environment where the impact of developments in research support by libraries has a significant benefit to the academic community within their institution.

Over the past decades, academic library services have evolved significantly, in particular with the revolution to a digital or e-research environment. A visit to an academic library website will reveal a wealth of services and products supporting research – from special collections to tailored support services.

Research ethics is an area that has benefited from the new library services that have been created to enhance research activity. Together with established services that support research more generally, services have been extended to provide strong support for compliance with, and capabilities to deal with, research ethics matters.

Applying the lens of research ethics to library activities provides the opportunity to reveal an important value from modern academic libraries. The work of the library in this area is vital infrastructure for successful research within institutions.

Research ethics and integrity

The study of ethics reaches back to the Greeks. Aristotle (Aristotle 1999, Aristotle 2002) proposed a philosophy of ethics that was a new and separate area of discourse. In summary, the approach was one that proposed that “moral virtue is the only practical road to effective action” (Sachs, n.d.). National and international research ethics standards have evolved dramatically since World War 2. The Nuremberg Code, established in 1948, is recognised as the first formal codification (Weindling, 2001). It stated that “The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential”. For information professionals this codification represented new standards and the requirement for documentation to record processes, consents and approvals as an integral part of the research ecosystem.

Research ethics is now required for all human and animal studies, with extensive requirements from funders, governments and institutions. The principles developed to underpin the approaches reflect moral principles that are continually reviewed and tested. They are designed to ensure high ethical norms are met. The norms “promote the aims of research, such as knowledge, truth, and avoidance of error” (Resnik, 2020). Ensuring integrity through research ethics is achieved through a range of institutional services, including that provided by libraries.

Dimensions of library support for research ethics

Research and an analysis of the field of research ethics has developed a number of essential principles. These relate to the practices that are required for compliance and values that are relevant to the nature of the support services required for successful research.

Unpacking the major principles and mapping them to work of academic libraries reveals a wealth of effective and well used activities that are fundamental to ensuring researchers can be confident they are able to comply with research ethics. A well-established set of principles (Shamoo and Resnik 2015) includes the following:

Honesty

Strive for honesty in all scientific communications. Honestly report data, results, methods and procedures, and publication status. Do not fabricate, falsify, or misrepresent data. Do not deceive colleagues, research sponsors, or the public.

Integrity

Keep your promises and agreements; act with sincerity; strive for consistency of thought and action.

Openness

Share data, results, ideas, tools, resources. Be open to criticism and new ideas.

Transparency

Disclose methods, materials, assumptions, analyses, and other information needed to evaluate your research.

Intellectual Property

Honor patents, copyrights, and other forms of intellectual property. Do not use unpublished data, methods, or results without permission. Give proper acknowledgement or credit for all contributions to research. Never plagiarize.

Responsible Publication

Publish in order to advance research and scholarship, not to advance just your own career. Avoid wasteful and duplicative publication.

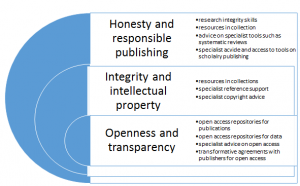

Analysing the range of academic library services against these principles provide an insight into the extent of library activities that support research ethics. A summary of the mapping (Figure 1) summarises collection, reference and research services that are all components of holistic support from the library for research ethics.

Figure 1. Mapping of library services to research ethics principles

The investment of academic libraries in collections and services to support research have had a significant impact on building the capacity of our institutions to support research ethics. The key strategic initiatives that have created great support in this area include:

- Digital collections that specifically support research ethics with a wide range of text books, journals and case studies including guides (such as lib guides) and researcher training to facilitate awareness and use of this material;

- Institutional repositories that provide open access to scholarly works including theses, preprints, OA copies of journal articles, non-traditional research outputs and other original research outputs. The most recent figures from Australian and New Zealand universities (Council of Australian University Librarians, 2021) reveal extraordinary strengths in this area. In 2020 (the most recent figures available), there were 1,650,867 resources available through Australian academic repositories and 135,712 through repositories in New Zealand universities. The impact of these in making research open and transparent is extraordinary. The 2020 figures reveal

Table 1.

Downloads from academic institutional repositories 2020 (Council of Australian University Librarians, 2021)

| Australia | 38,129,785 |

| New Zealand | 7,354,330 |

| Total | 45,484,115 |

The repositories enable researchers to both make their work openly accessible and access publications from others to increase knowledge of methods and research findings.

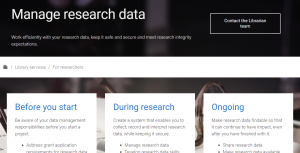

- Institutional data support services. Academic libraries now offer a wide range of data support services. These include research data management training, data storage and management of data repositories (such as the Australian National University Data Commons Service). In Australia, a significant program to develop the capabilities of library staff in data management has been delivered by the Australian Research Data Commons and its predecessor, the Australian National Data Services, a federally funded program (Australian Research Data Commons, 2022b). The University of Queensland Library guide on research data exemplifies the emphasis on clear information on data ethics (University of Queensland Library, 2022)

Figure 2. University of Queensland Library Research data guide.

- Specialised reference services have developed that support research with a strong component of research ethics. New courses include systematic reviews, publishing and publishing ethics, ethical writing, using tools such as Endnote and discipline based standards.

- Libraries provide specialist support on copyright and intellectual property. Most universities have a copyright specialist embedded in the library delivering training for researchers, answering enquiries and advising the institution of copyright issues.

Conclusion

Academic libraries are offering a wide range of activities that are vital to supporting researcher’s knowledge of, and capabilities, in relation to research ethics. The evolution in services and products, such as repositories and knowledge of publishing is of benefit to researchers in all disciplines. The evolution of national programs to support greater capabilities of library staff has been an important enabler of these developments.

The digital revolution has enabled greater and more effective outreach to researchers to embed these services across academic institutions. The library services have been vital elements in a partnership to address increasingly complex funder, government and institutional requirements for research. A recent study highlighted the importance of support in these areas (Jackson, 2018). The complexities identified to collect, transport, and store data in compliance with ethical requirements and managing data across the whole data lifecycle are well supported by the new library services.

There is a need to continue to develop the capabilities of librarians to be able to effectively support researchers with emerging issues, such as data management policy, privacy and security. Participation in national programs such as the Institutional underpinnings program for data (Australian Research Data Commons, 2022a) is an important element in this landscape. Over the next decade the evolution of services will provide an exciting area for the academic library community.

Roxanne Missingham, Australian National University

*

References

Aristotle. (1999). Metaphysics, Joe Sachs (trans.). Santa Fe, NM, Green Lion Press

Aristotle. (2002). Nicomachean Ethics, Joe Sachs (trans.). Newbury, MA, Focus Philosophical Library, Pullins Press

Australian National University. (2022). Data Commons. Canberra, ANU. https://datacommons.anu.edu.au/DataCommons/

Australian Research Data Commons. (2022a). Institutional Underpinnings. ARDC. https://ardc.edu.au/collaborations/strategic-activities/national-data-assets/institutional-underpinnings/

Australian Research Data Commons. (2022b). Resources for librarians. Canberra, ARDC. https://ardc.edu.au/resource_audience/librarians/

Bongiorno, Frank. (2022). The Humanities Laboratory. Canberra, The Australian Academy of the Humanities. https://humanities.org.au/power-of-the-humanities/the-humanities-laboratory/

Council of Australian University Librarian. (2021) Data file for CAUL statistics 2020. Canberra, CAUL. https://www.caul.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/stats/2020_caul_statistics.xlsx

Jackson, Brian. (2018) The Changing Research Data Landscape and the Experiences of Ethics Review Board Chairs: Implications for Library Practice and Partnerships. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44 (5), p. 603-612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.07.001

Resnik, David B. (2020). What is ethics in research and why is it important. Washington, D.C., National Institute of Environmental Health Science. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/resources/bioethics/whatis/index.cfm

Sachs, Joe. (n.d.). Aristotle: Ethics. Internet Encyclopaedia of philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/aristotle-ethics/

Shamoo, Adil E. and Resnik, David B. (2015). Responsible Conduct of Research. 3rd ed. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

University of Queensland. Library (2022) Manage research data. St Lucia, UQ Library. https://web.library.uq.edu.au/library-services/services-researchers/manage-research-data

Weindling, Paul. (2001). “The Origins of Informed Consent: The International Scientific Commission on Medical War Crimes, and the Nuremberg Code”. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (1): 37–71