Author: Jim O’Donnell, Arizona State University

Ireland is a country that has worked very hard on building its brand around the world, as befits a small country with a rich tourism industry. As IFLA prepares at last to bring the World Library and Information Congress to Dublin this summer, we should remember to appreciate the Irish tradition in librarianship. I have a tiny fragment of that history to tell you.

The title to this blog entry is in both of the official languages of the Republic of Ireland. I framed it that way to remind us of the distinctiveness of the culture and the challenges it has faced. Colonized by England and long oppressed, emerging from that shadow only with huge and painful difficulties in the twentieth century, and still in a relationship with the UK marked by potentially explosive tensions (as I write, the UK government is working very hard to exacerbate those tensions for the benefit of their ruling party), Ireland stands now stronger than ever before as a unique and distinct nation with an outsize part to play in the affairs of the world.

Traditionally known as the land of saints and scholars (hmmph, we muttered into our beer when I was a student there decades ago, priests and pedants more like it!), Ireland had a rich cultural heritage before Roman and Christian influences were felt. While WLIC participants are in Dublin, they will undoubtedly visit the Long Room in Trinity College Library, the most iconic library space in the world and home to fabulous treasures of medieval Irish culture – soon to close for three years of necessary renovation.

But I might encourage at least a few to walk a few blocks to the Royal Irish Academy in Dawson Street and ask to see the Cathach of Columcille. I can’t tell whether it will be on display, but it’s worth the ask. This is a Latin manuscript of the Psalms that scholarly experts date to the sixth century CE, and it comes with a story. It was discovered in the 19th century inside an elaborate protective case where it had been kept for at least three hundred years since it was put into safekeeping by the family that owned it at the time Irish independence was collapsing and the great princely families were hunkering down.

The story about this manuscript is that it was copied in the hand of St. Columcille himself (St. Columba for the Latin spelling) from an original that belonged to another man. When he had done copying, the owner of the original filed, yes, a copyright lawsuit, the first in history, against Columcille and the matter went to the local king for adjudication. “As the calf belongs to the owner of the cow,” said the king, “so the copy belongs to the owner of the original book.” You can sniff the whole future of copyright legislation and debates in those few words.

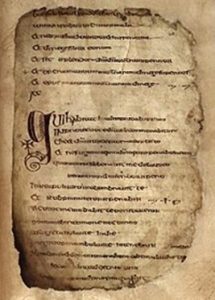

A page of the book:

The book’s case since the eleventh century:

Columcille harrumphed, and didn’t just harrumph. He fought a war to keep the book and successfully preserved it for himself and his community. Now, wars are not the sort of thing Saints and Psalm-copiers are supposed to engage in, so in consequence of his success, Columcille was given his penance for his sin: to leave Ireland and never lay eyes on it again. He sailed over the waters to the island of Iona and founded there a monastery that was a center of culture and learning for centuries after. Behind him, Ireland flourished as a Latin-writing and -reading culture and the Catholic church, with all its strengths and all its faults, remained central to Irish culture from that day till this.

Eventually, well after Columcille himself had died, the book he copied was carefully protected in a bejeweled case that goes back to the eleventh century and given to Columcille’s family, who used to carry it into their wars as a good luck charm. Cathach, the name for the manuscript now, is the Irish for “battler” or “fighter”. The family flourished for most of a thousand years with that good luck charm and their military fortunes and those of Ireland only faded when the book was relegated to safekeeping. The family held on to its keepsake fiercely but seems to have forgotten there was a book inside the lavish exterior. That ignorance may have been bad luck for the family in its battles, but probably good luck for preserving this evidence of the first copyright lawsuit.

Which family was it, you ask, that owned and abused this precious manuscript, then forgot about it, then found it again? Ah, that would be the O’Donnells, don’t you know? Feicfidh mé i mBaile Átha Cliath thú (oh, try Google translate on that one) – and we can talk about other Irish library stories then.