As much as anyone else, libraries work across a wide range of policy areas. Our institutions are engaged daily in work to promote research, support education, facilitate free access to information and expression, and deliver social inclusion. Library values and experience give us a unique voice in these debates, helping to support fairer, stronger and more sustainable development for all.

This breadth of activity can also be a challenge. No-one has infinite time to put into advocacy, and in any case, there is limited capacity amongst decision-makers, influencers and library-supporters. As a result, it is important to prioritise.

Therefore, in the first of what we hope to make a monthly series of blogs, we will be defining our ‘Advoc8’ – a set of 8 key messages that you can draw on in your library advocacy, from formal speeches to informal consultation, from letters to newspapers to social media posts. Where we can, in each post we’ll be providing links to further materials. From one month to the next, some of the content will change according to available opportunities for advocacy, while some will stay constant.

Let us know how useful this is (and we’re sorry about the cheesy title)!

1. We have a long way to until we achieve gender equality. Success requires addressing the information dimension of development, in particular through libraries

With 2020 representing 25 years since the Beijing Declaration and Plan of Action, there is global attention to what has been done, and what we still need to do, in order to ensure full gender equality. The Declaration itself highlights key areas related to information, including skills and lifelong learning, access top health and legal information, digital inclusion and broader awareness-raising, where libraries make a difference. IFLA’s analysis shows how many countries have recognised this, and in doing so, provide an example for others. See our briefing on the Declaration and our analysis of the national reports.

2. Our documentary heritage is both precious and at risk. Governments need to act – through law, policy and funding – to support its preservation.

The documentary heritage held in the collections of libraries and other institutions represents the memory of the world – the ideas, innovations and expressions that make us what we are today. Yet too often, this documentary heritage is overlooked in cultural and other policies. A lack of investment in its preservation, inadequate policies, and incomplete legal frameworks can lead to irretrievable loss. UNESCO’s 2015 Recommendation provides a valuable reference point, but uptake and implementation needs to be strengthened. See our briefing on the Recommendation, and new checklist allowing libraries and library associations to assess how well it is being put into action.

3. Meaningful access to the internet is a driver of development. Public access in libraries plays a key part in delivering it, affordably.

Over half of the world’s population now enjoys internet access, a major achievement. As we approach the 31st anniversary of the World Wide Web, it is worth remembering that this still means that billions of people remain offline. Furthermore, there is a growing awareness that simply having the physical possibility to access to the internet does not always mean people are getting the most out of it. Institutions such as libraries, offering good connections, necessary hardware, relevant skills and support, and simply a space for internet use have a well-established role in promoting digital inclusion, affordably. Look out for our communications on 12 March about the anniversary of the World Wide Web, and see our analysis of how libraries are already included in national broadband strategies.

4. Libraries are essential partners for local government in delivering the SDGs locally. We are ready to help: there are almost 430 000 public and community libraries around the world, strongly focused on meeting the information needs of the local areas they serve. They have much to contribute to wider efforts by local government to deliver on the Sustainable Development Goals, in many different ways, from supporting skills development and internet access to providing an information point and portal to local open government data. When fully integrated into local government planning, they can not only support cultural development, but support the success of a wide range of policies. See our list of ten roles libraries play in supporting effective local government, and our briefing on what the New Urban Agenda means for libraries.

5. The skills to find, analyse and evaluate information are vital. Libraries are ideal places to develop these: we have never had access to so much information! There is a greater possibility to find and use more content than ever before at any time, anywhere, creating exciting new possibilities for free expression, innovation, and forming communities. To do this, people need to be able to navigate through all the information available, and for this, information skills are essential. Faced with unreliable or deliberately false information online, our best hope in building a sustainable and equitable information society is to promote media and information literacy skills for all. Look out for communications later this month about IFLA’s engagement in a project to boost media literacy skills in a number of European countries.

6. Everyone – and in particular children – has the right to engage in cultural life and access materials reflecting their experience.

The right to participate in the cultural life of the community is a fundamental right, set out in Article 27a of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. When this right is denied, quality of life is diminished, and risks of alienation and lack of resilience rise, making the achievement of broader development goals more complex. In education in particular, better results can be achieved when students are able to engage fully by having access to materials that reflect their cultures and use their language. Libraries bring a unique expertise and possibility to do this. See our submission to the UN Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteur on Cultural Rights for more.

7. Gathering, organising and giving access to data and information is at the heart of successful open government policies. Libraries make this happen: the role of good governance is highlighted by SDG16, with transparency at its heart. When citizens can find out about what those in power are doing, and use this information in order to hold them to account, there is greater pressure to take decisions that are in the public interest. Achieving this is about more than just online portals – not only does the information need to be structured properly, but citizens often need help to understand what is there and use it to draw their own conclusions. Libraries are ideally placed to do this, with many great examples already out there. For more, see our blog on libraries and open data.

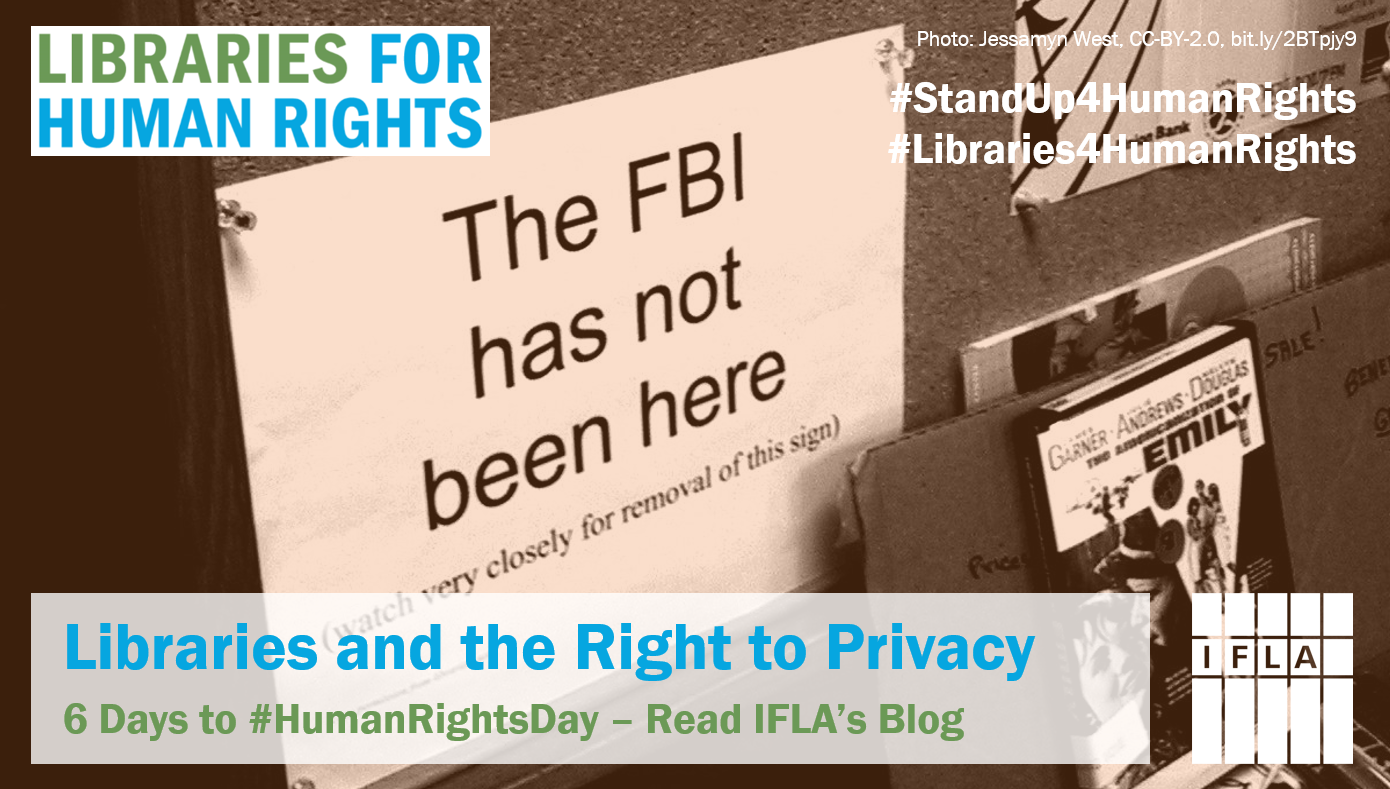

8. New protections for privacy are welcome, but cannot lead to the destruction of library and archive holdings: a new generation of data protection laws are giving citizens new power to understand, control and even delete information held about them by others. This is potentially a major breakthrough in efforts to make a reality of privacy in the digital age. At the same time, concepts such as the ‘right to erasure’ bring the possibility of efforts to remove references to individuals and their actions held in archival collections. This can lead to holes appearing the historical record, as well as making it more difficult for future researchers to understand the world of today, or to ensure transparency of decision-making. New laws should therefore protect archiving rights as part of the balance between freedom of access to information and expression, and the right to a private life. See the new IFLA-ICA Statement on Privacy Legislation and Archiving for more.

In the last of our series of blogs in the run up to Human Rights Day, we’re looking at situations where different human rights risk being in tension with each other. We argue that in a number of key areas of potential clash, the work, professionalism and ethics of librarians offer a valuable response.

In the last of our series of blogs in the run up to Human Rights Day, we’re looking at situations where different human rights risk being in tension with each other. We argue that in a number of key areas of potential clash, the work, professionalism and ethics of librarians offer a valuable response.