Paul Romer, one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Economics 2018, has been recognised for his work on how innovation can allow for continued growth. His insights into the nature and role of knowledge – and in particular of access to knowledge – offer welcome support for some of the key functions of libraries in providing access and skills to all.

Libraries and economics are rarely seen together in the same sentence. Indeed, libraries are seen by many as the reverse of economics – a public service aimed at promoting well-being. A long way away from business and profits.

They are, arguably, the answer to the failures of free market economics, which would risk seeing people on low incomes, or who are otherwise disadvantaged, neglected by businesses.

However, the Nobel prize for economics offered a couple of weeks ago to Paul Romer, alongside William Nordhaus, provides an important affirmation of what libraries do.

Paul Romer’s key achievement has been to create models that explain the contribution of research and innovation to long-term growth. The key document here is his 1990 article on Endogenous Technological Change.

Rather than seeing the development of new ideas it as something external, Romer underlines that it was possible – in theory as well as fact – for economies to keep on growing thanks to investing in research and innovation.

Importantly, this also meant that it wasn’t just the number of people, or the amount of capital (machines, computers, investment) that determined growth, but the skills of the population – human capital – that counts.

Why Knowledge – and Access – Matters

The key factor in Romer’s calculations is the unique nature of knowledge.

He underlines that knowledge – ideas – are not ‘rival’. Unlike a piece of food or clothing, one person having an idea does not mean that someone else cannot. Ideas are not exhausted by being known or used.

They are also not easy to keep to yourself. Economists talk about excludability – the possibility to prevent other people from using things. This is easy with a piece of food or clothing, but not so much with ideas and knowledge.

There are intellectual property rights, which create legal possibilities to exclude others from ideas as a means of ensuring some return on investment. However, as Romer’s model sets out, this exclusion is only ever partial.

Because in Romer’s model, it is the fact that knowledge is accessible – that it contributes to the sum of human knowledge – that means it can have such a positive impact on growth.

Once an idea or piece of research is produced, it feeds into the work of others, who can then come up with new ideas and research. While intellectual property rights stand in the way of reproducing and selling the same piece of work, it is possible for everyone to be inspired by it, and go further.

This removes the limits that a certain population – or amount of capital – places on growth. Thanks to wise use of knowledge, promoting accessibility while finding means of rewarding creators for their work, it becomes easier to sustain the growth that pays for crucial public services.

Libraries and Open Access

There is plenty here that speaks to the role of libraries.

As institutions dedicated to supporting access to knowledge, libraries play an important role in realising Romer’s key point that innovation benefits from full access to the stock of existing ideas.

Romer underlines the importance of trade in facilitating the spread of ideas and innovation. Libraries, through cross-border activities, help achieve the same.

Open Access plays a vital role here. Free and meaningful access makes a reality of Romer’s suggestion that new ideas join a stock that is available to researchers and innovators everywhere as a basis for further progress.

Paywalls risk weakening this effect, and this potential.

For researchers in countries at risk of being left behind, they can lock them out completely. One of the more chilling conclusions of Romer’s work is that in some situations, there risks being no incentive to invest in research, seriously damaging the country’s growth prospects. We need to fight against this.

Clearly, free does not always mean accessible. If there is no effort to make a piece of research easy to discover and use, it will not really join the stock of knowledge out there promoting human progress.

Libraries help here also through managing repositories, developing standards, and helping researchers find what they need.

Libraries also respond to Romer’s key policy recommendation – the value of developing human capital (skills) in an economy. This – rather than efforts to extract money from those who make further use of ideas in order further to support rightholders – is the most practical way to boost innovation.

Paul Romer’s ideas have had a major impact on how governments, and intergovernmental organisations think about growth, and how to support it. While not mentioned in his key article, supporting libraries and open access seems a good way to go about it.

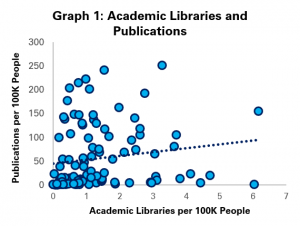

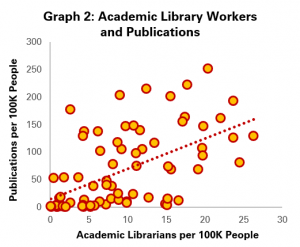

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1).

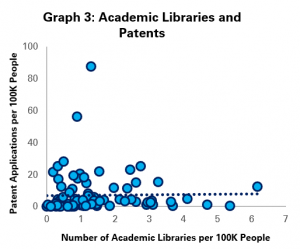

Interestingly, the correlation is stronger in the case of academic library workers (Graph 2) than in that of academic libraries (Graph 1). Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people.

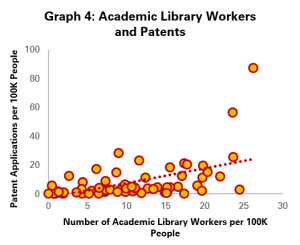

Graphs 3 and 4 therefore repeat the exercise with patent application data, comparing numbers of academic libraries and library workers per 100 000 people. Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.

Nonetheless, on the stronger indicator of the strength of academic library fields – the number of academic library workers per 100 000 people (Graph 4) – the correlation does reappear, although is still slightly weaker than with publications.