This 9 – 13 May, I attended the 42nd meeting of the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Standing Committee on Copyright and Related rights (WIPO SCCR/42 for short). For a week, national delegates, expert panels, and observing civil society organisations (CSOs) like IFLA and rightholder groups discussed the impact of COVID-19; the WIPO African regional group’s proposal for a workplan on limitations and exceptions; broadcast rights; and other odds and ends for some 40+ hours’ worth of meetings, coffee breaks, and side discussions. Conversations advanced and some commitments were made – including items on studies and toolkits on copyright limitations and exceptions.

It was my first trip to Geneva, so it was the first time I experienced the process. WIPO is the World Intellectual Property Organization, and indeed ‘IP’ is the general framing of Why We’re All Here. Creative outputs and patents are primarily considered valuable because they’re monetizable. The affective dimension (whether you ‘like’ a book) or the work’s value for humanity as a whole occasionally peaks through when civil society organisations (CSOs) or expert panels re-frame the issues, or (as happened twice, by my count) one of the invited artists on a panel delivers an a Capella performance.

By contrast, imagine a framework that began with ‘art and information are good, and people should have better access to those things’. It would be a very different conversation, for example, than that presented by WIPO’s expert report on how COVID-19 affected rightsholders and cultural institutions. There, the ‘Cultural Heritage Institutions, Education and Research’ section contained language about balancing access with rightholders’ interests that were largely absent the other way around from the rightholder sections.

In the observer section of the main room, CSOs sit alongside industry organisations. We’re there to represent our constituents’ interests and have our views heard, but it’s up to the delegates to make the votes. The ‘rightholder’ side tends to represent publishers, record labels, and other aggregators and content distributors moreso than creators directly. The tension could be felt, for example, during Thursday’s presentations on streaming music in which expert presenters underlined that compensation was scarce for non-featured artists. This tracks with online discussions I’d followed, along with standard-issue rock-n-roll lore about bands’ conflicts with their labels.

This is all also to say that delegates are engaged in a delicate push and pull between interests, and from the rightholders (and to some extent, us CSOs), like shoulder angels and devils, there can be an adversarial tendency to avoid wanting to lose any ground. So, with regard to limitations and exceptions to copyright – which enable libraries and individuals to lend, share, and make use of all kinds of material – the ‘opposite side’ can sound a bit like Groucho Marx laying out his platform on ascending to the university presidency in Horse Feathers – ‘whatever it is, I’m against it.’

(Side note: while I was unable on a quick search to locate the copyright status of Horse Feathers, the Marx Brothers were once themselves fined $1,000 for copyright violations; Groucho also responded to Warner Brothers’ fears that the then-forthcoming A Night in Casablanca [1946] would infringe on their film Casablanca [1942] by jokingly threatening a counter-suit over the word ‘Brothers’. Copyright has never been easy to sort out, or straightforward.)

Back to the Statute of Anne (1710), the first copyright law, copyright was intended to be a broad ecosystem that protects rightsholders’ right to compensation, and the public interest in having access to and working with materials. This includes the right to quote (on an obligatory basis), as well as possibilities to make a copy of a chapter, to use in the classroom, to offer commentary, to remix in ways not in competition with the original work. A robust copyright system enables different interests to be represented.

In respect to these positions, there are many good reasons for strong limitations and exceptions – including with respect to the broadcast rights, which came to the fore on the Tuesday and Wednesday in discussion of the Broadcast Treaty, which aims to protect broadcast signals (the medium, not the content). It has been under discussion since the late 90s.

Going forward, IFLA plans to highlight the importance of limitations and exceptions to preserve the right to archive and preserve broadcasts. Preservation shouldn’t have to be the sole responsibility of increasingly conglomerating commercial entities most immediately concerned with short-term profits. Cultural institutions are well equipped to collect, curate, and make available – if they don’t face dissuasive economic and administrative barriers to doing so. Here, archives and rightsholders have slightly different, but complementary & related interests. A key question, if you’re making content is: do you want your work to be accessible a few decades down the road?

One need only look to how much things have changed SINCE the broadcast treaty entered onto the agenda in the late 90s. For consumers,staring at screens in their homes, this period saw changes from standard definition to high definition, and from VHS to DVD (with detours into VCD in Asia) to Blu-Ray to streaming. Once-ubiquitous CRT monitors are currently a fad for retro gaming, as graphic designed for their slightly blurry displays and can look disconcertingly jagged on a modern 4K OLED, where every single one of the 8,294,400 pixels can show a different colour from its neighbour. Radio stations consolidated or went out of business. Long-running shows end, inevitably – and have to find archival homes for their collections or junk them. You’re lucky today to find equipment today that plays old consumer, professional and semi-professional storage formats, or to access files on the editing hardware and software from eras past.

This is all living memory, and underscores how difficult it is for people to ‘watch’ TV like they did 25 years ago. To preserve that content and experience, archives play a key role – and need broad flexibility to capture, store, back up, and engage with content amid these changes. Sometimes, cool discoveries are made – like the recent find of a Minnesota TV station in their archives of a video of the musician Prince, at age 11. We can share that this discovery happened, beyond a local TV station, in part due to broad access rights.

As these discussions continue, support libraries! Please don’t create new barriers to preservation through new rights and impositions, but rather support proper exceptions and limitations to help libraries, archives and other institutions do their jobs preserving content and making it accessible.

Matt Voigts, Copyright & Open Access Policy Officer

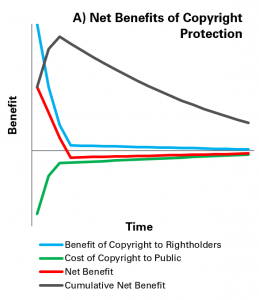

Graph A offers a way of reflecting on this, for a complete set of works published in a given year. The horizontal axis represents time after publication, and the vertical, benefits/costs. Figures are not included, as the graph provides a model, rather than a set calculation, and because it can be hard to put a clear figure on monetary costs or benefits to some things.

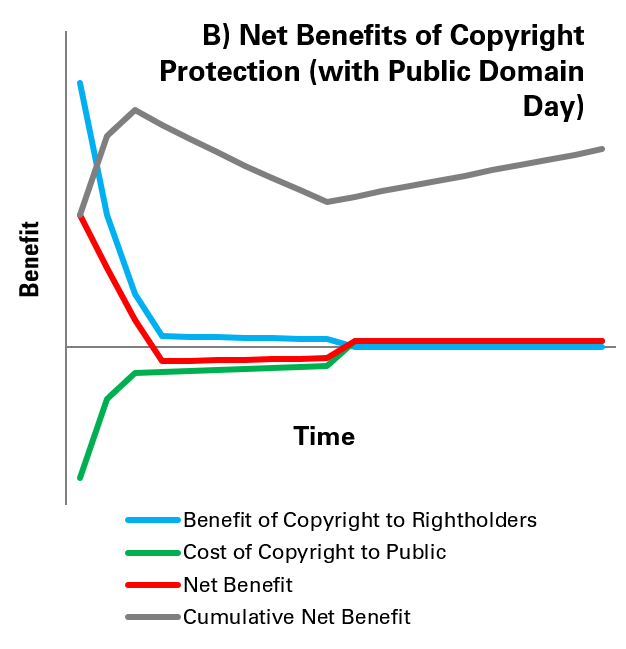

Graph A offers a way of reflecting on this, for a complete set of works published in a given year. The horizontal axis represents time after publication, and the vertical, benefits/costs. Figures are not included, as the graph provides a model, rather than a set calculation, and because it can be hard to put a clear figure on monetary costs or benefits to some things. Entry into the public domain provides a response to this situation of a falling cumulative net benefit over time. Graph B illustrates this. At halfway along the horizontal axis, works from a given year enter the public domain, and so benefits to rightholders from sales and licensing fees (blue line), which were already low and falling, are reduced to zero. However, the costs to the public (green line) also disappear, and in fact turn into benefits as people are able to use and enjoy works freely.

Entry into the public domain provides a response to this situation of a falling cumulative net benefit over time. Graph B illustrates this. At halfway along the horizontal axis, works from a given year enter the public domain, and so benefits to rightholders from sales and licensing fees (blue line), which were already low and falling, are reduced to zero. However, the costs to the public (green line) also disappear, and in fact turn into benefits as people are able to use and enjoy works freely.