We talk a lot about the importance of access to information in advocacy around libraries.

This access is at the heart of what libraries themselves do of course, helping users to find the information that they need to take better decisions, and participate in the life of the community.

Our institutions have been doing this for thousands of years, helping leaders, researchers, creators and other citizens to achieve their missions.

In advocating, we focus on why this matters so much, underlining how, in different policy areas – healthcare, innovation, democracy itself – access to information helps deliver goals, and in turn, how libraries deliver this access in an equitable way.

However, in doing this, it’s worth keeping in mind the different issues that access encompasses, and the different struggles this can imply, if only to be clear for ourselves.

This blogs therefore looks at just ten different aspects of access, and how this can play out in work on library advocacy.

1) Access as the possibility to find a work in the library: libraries have a key role in ensuring that ability to pay does not become a determinant of whether people can enjoy their right to information. This applies as much to those who would not be able to buy textbooks or children’s books, as to those who may only need certain parts of a book, and are not ready to pay for the whole book just to access extracts.

This is why it is so important that libraries can acquire all types of material, without barriers. Unfortunately, refusals to sell to libraries (or only to do so under very restrictive terms) make this difficult, and arguably require further investigation.

2) Access as preservation: access is an ongoing priority, and one that is threatened by the loss of materials due to decay, destruction or other reasons. It is particularly important – for researchers, for citizens – to know that todays information will be available into the future, in order to make it possible to support re-evaluation and accountability.

For example, government records need to be saved to allow for future study into decisions taken, while science itself is based heavily on the idea that research results should be reproducible – i.e. future researchers can access the same materials and reproduce the results of experiments.

3) Access as (reliable) connectivity: with so much information available online, including many materials that may previously have been produced in physical formats, internet access has become almost unavoidable as a form of wider access to information.

IFLA focuses strongly on this, underlining the need for libraries and users to benefit from high quality connections that are reliable – it is unlikely that people and businesses will be ready to invest in internet-enabled activities and approaches if they cannot be sure that it will stay on.

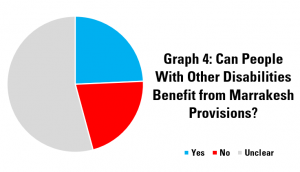

4) Access as a lack of barriers: access is not just about whether the library itself can add – and maintain – works in their collections, or whether they can connect meaningfully to the internet. Access is about whether library users can take advantage of this possibility. To do this, we need to work towards the absence of practical barriers to use, such as those felt by people who live far from a library, or who face challenges linked to physical mobility or other disabilities.

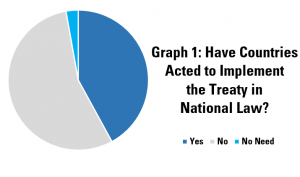

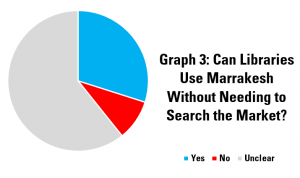

A number of tools can help in this regard – the internet is an important one of course – as can the sort of reforms promoted by the Marrakesh Treaty, that helps ensure that copyright does not pose an unreasonable barrier to creating and sharing accessible format works. With over 100 countries now signed up to the Treaty, we can aim for universal coverage in the coming years.

5) Access as literacies: access is also, crucially, about the skills of the person receiving information to understand and make sense of it. The skills involved can go from basic literacy to much more advanced forms, including critical thinking. Especially for those trying to work through the wealth of information online, being able to find the right knowledge is vital.

Basic literacy has long been an area of library expertise and experience, with increasing efforts to take information literacy training out of academic libraries and into public ones, to the benefit of the whole population. A priority here is to ensure that such support continues to be available to all, throughout life .

6) Access as use: access can imply a relatively narrow way of using information – for example being able to take, open and read a book. However, while for some library users this may be enough – simply taking pleasure or interest from the words on the page – for others it is not. They need to be able to quote, analyse or otherwise use works. For them, access without the possibility to use is pointless.

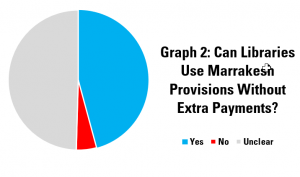

This is a core point around much work on copyright, with libraries arguing that once they have legally acquired a work, a core set of uses should be possible without restrictions or additional payment needed. These uses should be seen as part of the original price paid. Clearly this would not count uses that could cause unreasonable harm to rightholders, but trying to licence every single type of use is a recipe for market failure.

7) Access as the counterpart of expression: as set out in the previous point, a key ingredient of access is the possibility to use the information found in future work. As well as copyright issues, this can also implicate wider ones about freedom of speech. This is because the possibility to access and use information is less powerful if there are then limits on what can be done with it due to censorship or other controls.

It goes without saying, as well, that the fact that there is a variety of information to access in the first place depends heavily on the possibility for creators to express themselves and produce works in the first place. This is why libraries are encouraged to do what they can to champion intellectual freedom.

8) Access as relevant content: closely linked to the first point is the importance that people can find information that is relevant to them. This can be a question of finding books and other materials in the right language, and that tackle the issues that matter for the reader.

Clearly, the internet has created exciting possibilities for people without access to publishing houses, distribution networks or radio stations to share their ideas. However, it can also encourage a narrowing of horizons onto a single global set of materials. A key challenge then for libraries is to understand what materials users need, and to identify and provide access to this, including by promoting further creativity,

9) Access as feeling welcome: closely linked to the previous point, as well as those on skills and disability, the possibility to engage meaningfully with information can depend in large part on the possibility to relax and focus. This raises the question of how to ensure that people feel welcome and comfortable in libraries – and other places where information is accessed.

This can make a big difference for people who may feel otherwise excluded, For example, those with low literacy may feel intimidated by libraries, or those looking for information about very personal issues may feel awkward otherwise. It is therefore important, as part of all policies focused on access, to help people feel at ease, and avoid steps that could discourage information seekers.

10) Access as privacy: while linked to the previous point about feeling comfortable, the value of privacy in information access cannot be underestimated. Feeling that you have someone looking over your shoulder (literally or virtually, thanks to cookies or other digital tools) can have a chilling effect, limiting what a user is ready to look for.

This is why protecting privacy in the library environment, and doing what is possible to help users of third-party services to keep themselves safe, is such an important part of ensuring that access is meaningful for all.

We hope that these ideas are useful for you in thinking about the ways in which we talk about access, and welcome further ideas in the comments below!