In last week’s Library Stat of the Week, we explored in more depth the relationship between numbers of students and researchers as a share of the population, and numbers of academic and research librarians available to support them.

This helped to highlight the variation that exists between countries, and in particular which ones manage to combine a strong student or research sector with adequate librarian support.

Having figures for the number of students and researchers allows us to look at potential relationships between the level of library support they receive (calculated in terms of the number of students or researchers an individual academic or research librarian serves) and outcomes.

Therefore, in this week’s Library Stat of the Week, we will be using, for the first time, OECD data on tertiary education completion rates (as a measure of whether students receive the support necessary to finish their courses), and publishing and patenting data, as used in previous editions.

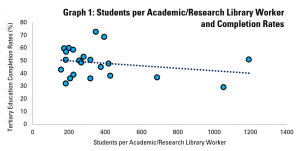

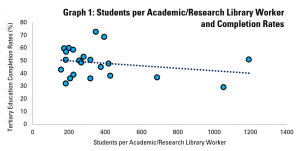

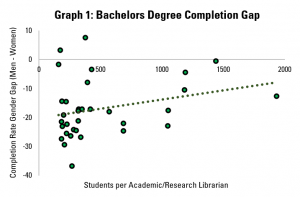

Graph 1 looks at completion rates (from OECD data, for students at all levels) and compares these with previously calculated figures about the number of students each librarian serves on average.

It finds a small, negative correlation between the two – in other words, the more students an academic/research librarian needs to serve, the lower the likelihood of the student completing their studies.

Clearly, other factors also play out – the OECD itself notes that where courses are shorter, completion rates are higher, and of course student financing also plays a role.

Nonetheless, while of course this sort of analysis cannot show causation, it does indicate that where students have greater access to librarians, they are more likely to complete their courses.

Turning to research, our previous posts looking at the relationship between libraries and innovation were based on numbers of academic/research library workers in the population as a whole.

This, while showing that more librarians tended to mean more publications and more patents, had the weakness of neglecting indicators of the strength of the research field as a whole.

To remedy this, we can now use figures from the last two weeks which calculate the number of researchers each academic/research library worker has to serve, giving a much better idea of whether more (or less) library support for research correlates with outcomes in terms of publications and patents.

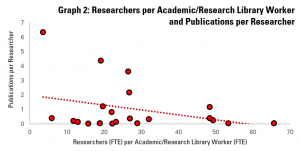

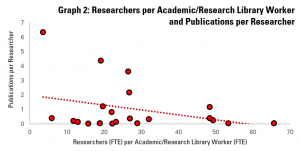

Graph 2 does this for publications, looking at whether researchers with more academic library support tend to publish more. To do this, we created a measure of number of publications per researcher by dividing figures for numbers of publications (World Bank) by those for the number of researchers (OECD).

The graph does indeed show this – when each academic/research library worker has fewer researchers to serve, the researchers tend to publish more articles each.

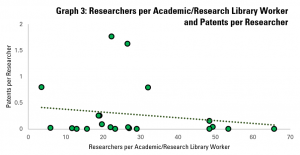

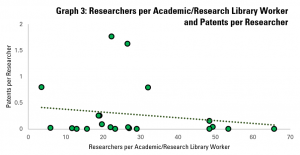

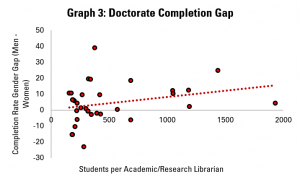

Graph 3 performs the same exercise for patents, using a figure for patents per researcher calculated again using World Bank and OECD data.

As with publications, this again shows a correlation, with countries where each academic or research library worker needs to serve fewer researchers each, on average, having higher rates of patenting per researcher.

As ever, correlation is not causation, although the analysis here does allow us to focus more precisely on the relationship between the strength of the academic and research library field and innovation performance per country.

While further research would be needed in order to demonstrate direct causality, these figures do allow us to say that those countries which provide stronger library support to students and researchers (as measured by numbers of students or researchers per academic and research library worker) tend to have higher student completion rates, and higher rates of publishing and patenting per researcher.

Find out more on the Library Map of the World, where you can download key library data in order to carry out your own analysis! See our other Library Stats of the Week! We are happy to share the data that supported this analysis on request.

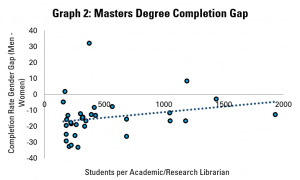

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.

Across the three graphs – and so at all levels of study – it appears that where there is greater level of support from librarians (i.e. each librarian has fewer students to support), the gender gap is more favourable to women.