The COVID-19 pandemic is having a huge impact on our lives, societies and economies. Millions have fallen ill, and billions have faced restrictions on their movements, with early evidence indicating serious economic consequences.

The next months will reveal more about how quickly it will be safe to lift the controls in place, and what the ‘new normal’ will look like. Beyond the measures based on scientific evidence, there will be crucial, more political, decisions to be made about the sort of world we want to build.

A key focus will be around the protection – and guarantees – offered for the political, economic, social and cultural rights of individuals and groups.

IFLA’s own statements on library values – the Public Library Manifesto, the Position on Intellectual Freedom, on Privacy in the Library Environment, on Net Neutrality, on Internet Shutdowns, on Public Legal Information in the Digital Age, on Fake News, and on Censorship – highlight not only libraries’ broader commitment to human rights and equality, but also a specific focus on access to information and education, the right to a private life and participation in political, economic, social and cultural life.

As this blog will set out, the COVID-19 pandemic has led governments to implement – or fail to implement – measures which raise serious concerns, in particular in fields where libraries are focused. It has also highlighted areas where certain groups are hit harder than others, violating the principle of equality. Finally, it has thrown light on subjects where it is necessary to find a balance between rights.

Direct Violations

A first category of issues is those where there is a clear violation of rights and library values at play, affecting everyone.

A crucial area where we have seen rights risk being unjustifiably undermined concerns privacy. With many people more reliant on the internet than ever, the need for those providing services need to respect private lives. For libraries, this is particularly true when it comes to providing access to digital services, including remote access to collections, eLearning, as well as more broadly for enforcing academic freedom.

Crucial to this is to give users a real choice over what data they do hand over, and under what conditions. Users need to be able to trust what they are told by companies, and need to have the opportunity to enforce privacy when they want. Where this is not the case, something is wrong.

For young people in particular, who may have fewer chances to choose, it cannot be acceptable to gather data by default during learning – a point also highlighted by UNICEF – while efforts to prevent cheating in exams should not be implemented without proper consideration of ethics. A similar point of course goes for checking up on employees working from home.

In the above cases, violations will primarily be committed by private actors. The role of government is to enforce rules that prevent these. However, there are also instances of direct violations by those in power.

An obvious example is in the steps that some have made to limit the rule of law. Detention without trial, closure of courts (or restriction of access), unjustified surveillance and refusal to allow for any democratic influence over when emergency powers are lifted are clearly all deeply troubling.

Emergency powers too, clearly, should not provide an excuse to take other decisions which are not urgent, or not related to the pandemic, without scrutiny or discussion – a point which can also apply to any organisation.

Similarly, it is unacceptable to fail to keep records of the decisions made during this period, which will be essential for future evaluation and accountability, as set out in the International Council on Archives’ statement. With libraries too having a key role in collecting, preserving and giving access to laws, this is a crucial point.

Finally, and also of high relevance to libraries is the impact of the crisis on the rights of access to education, research and culture. The shift to remote working has exposed the weakness of many copyright laws, which allow rightholders to impose restrictions on how digital works are used, overriding copyright exceptions set out in law.

While there have been many welcome efforts to change practices to allow for distance uses, it should not be the case that key rights – to education, to participate in cultural life, to benefit from scientific progress, and to access to information – should depend on private goodwill. As the Director General of the World Intellectual Property Organization has set out, extraordinary times can justify targeted adjustments to copyright laws in order to allow access to continue, a point also highlighted by Communia.

When governments or private actors take steps that affect the rights of whole populations, libraries and their users are inevitably affected. They are particularly hard-hit by failures to ensure that laws allow them to continue to fulfil their missions.

Unequal Treatment

A second category of issues where fundamental rights come into play is round unequal treatment. The pandemic has both triggered new forms of prejudice, and has shone a light on pre-existing inequalities in our societies. Here too, there is a pressing need for action.

A clear example are attacks on foreigners – or people of foreign descent – who risk being seen as somehow responsible for the disease. This form of open discrimination is clearly counter to the values of libraries, which act to serve people everywhere regardless of background or other factors.

While – fortunately – many governments have not sought to encourage such feelings, there is still a pressing need to act to promote tolerance. Clearly where governments are encouraging such sentiments – for example through the expulsion of journalists of certain nationalities – this should stop.

Secondly, plenty has already been written about the evidence that certain groups are more at risk than others of catching or dying from the disease itself. Those who are older, have specific conditions, or are in prison, as well as those for whom it simply isn’t possible to practice hygiene or social distancing, need help.

The impacts of restrictions imposed in response to the pandemic has also been uneven. People in insecure or informal work have often been among the first to lose their livelihoods, as well as those in sectors most badly affected. While some are lucky to live in countries where the government can step in to help, this is not the case for all.

Given libraries’ commitment to equality and equity, any situation where some groups end up worse off than others is troubling. Libraries have of course been working hard, around the world, to continue to support all parts of the communities they serve, even under current circumstances.

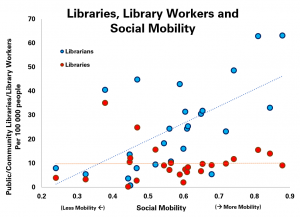

However, this has certainly been harder where digital solutions do not provide a response. Globally, nearly half of the world’s population is still not online. Some of these are subject to politically-motivated internet shutdowns. Of those who are, many still lack the speed of connectivity, or hardware, to make full use of the internet, leaving them on the wrong side of the digital divide.

As a result, due to the slow progress of efforts to ensure universal connectivity, some are less able to enjoy their right to education, research and culture than others. For example, statistics from Los Angeles County in the United States underline that 25% of students are not in a position to benefit from distance learning.

Libraries have of course been active in trying to address this. Efforts to boost connectivity have come through providing long-range WiFi, or lending hotspots and hardware. Programmes for developing digital skills are being rolled out. Physical deliveries of books and other materials – with maximum precautions taken for hygiene – are helping those who cannot come to the library continue to benefit from services.

Libraries are also active in promoting participation in exercises like the census in the United States, which has a key impact on the funding different areas receive in order to carry out pro-equality policies. Delay to these – or incomplete answers – risk making it harder to address challenges like universal internet access in future.

As institutions with a mandate to provide universal service and to promote equity, the inequalities exposed by the pandemic will be a clear sign for libraries of the need for stronger laws and more effective support for solutions.

Finding the Balance

A final category of issues is those where different rights risk coming into conflict. This is foreseen in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, whose Article 29(2) underlines:

“In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society”.

In the case of COVID-19, it is clear that action to protect health is a priority (the right to health is set out indeed in Article 25), and so may provide a justification to limit rights. However, when this happens, it is crucial to find a balance. Limitations need to be proportionate, going no further than necessary, be implemented in a transparent and accountable way, and be lifted as soon as possible.

In this respect, the privacy implications of contact-tracing apps – effectively surveillance of individuals through their phones – have received particular attention in media discussions. Clearly, the question of how to identify people who may have been exposed to the virus and recommend quarantine was already raising privacy questions before talk of apps.

Stories of the publication of names of people who had caught the disease are worrying. So too is the tracing of specific mobile phones, for example by nationality. These steps are, arguably, disproportionate to the goal pursued, with alternative approaches available.

As for contact-tracing apps themselves, there are ongoing discussions about whether this can be done effectively without the collection of extensive personal data, and challenges to technology companies to prove that their apps are worth the intrusion.

Already, some argue that apps can work without collecting geolocation data – for example – by working only with relative data (i.e. who have you been close to, rather than where have you been). Nonetheless, this can also reveal private lifestyle information. It may be possible, some have claimed, to limit risks by only holding data on phones – rather than centrally – but there are also worries about how quickly this may drain batteries.

Finally, there is concern about making the downloading of apps obligatory, while others worry that insufficient take-up of apps will make them ineffective in the effort to contain the disease.

Another area where there is need for care is in finding the balance between freedom of speech and steps to stop the spread of misinformation that can damage efforts to tackle the pandemic.

This is not a new issue, but the sense of urgency in removing misleading reports and stories has led to the rapid introduction of new measures, not always with full debate. There is clearly a need for action, not least to avoid a desire for clicks and attention incentivising the creation and sharing of false facts.

Nonetheless, this needs to be done while still prioritising the promotion of media freedom and quality journalism. While the blocking of demonstrably false and malicious content may sometimes be justified, banning opinion pieces and preventing access to information, as well as imposing fines or jail terms for supposed offences are likely to have a major chilling effect.

The situation has been made more difficult still by the fact that people employed to moderate content are often forced to stay at home, increasing reliance on filters powered by artificial intelligence which remain deeply flawed.

For libraries, the importance of both privacy, and freedom of expression and access to information needs to be recognised fully in all decisions taken. As set out at the beginning of this section, any restrictions need to be proportionate – i.e. they should not to go any further than necessary, and there should not be any less intrusive alternatives – and need to be carried out transparently, and not apply for any longer than necessary.

In this context, libraries have a logical role in advocating for less intrusive approaches to contact-tracing and efforts to counter ‘fake news’. Instead, they can use their expertise and networks to promote media literacy and a better understanding of the privacy implications of the choices they make.

The COVID-19 Pandemic certainly represents an extraordinary moment, and one which certainly calls for extraordinary measures. Nonetheless, there remain constants, not least the importance of protecting and guaranteeing the fundamental rights of all, which must be at the heart of the societies we build post-COVID-19.

As this blog sets out, there is an immediate need for action to put an end to unjustified violations of rights of all sorts, whether they affect whole populations or only particular groups. There is also a need for close and careful monitoring of any measures that seek to balance different rights.

Thanks to their values and their skills, libraries are well placed to take actions to help ensure that rights are not violated as a result of measures imposed during the pandemic. However, a truly rights-based, equal society in future will need actions from all.

With a fundamental mission to serve their communities at a time of unprecedented social, technological and economic change, libraries are busy places!

With a fundamental mission to serve their communities at a time of unprecedented social, technological and economic change, libraries are busy places!