“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

Freedom of access to information and freedom of expression is guaranteed under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR). It provides a powerful basis for efforts to ensure the free flow of information.

As IFLA has argued, access to information is at the foundation of successful development policies, by ensuring not only that everyone can make better choices themselves, but can also take part in collective decision-making.

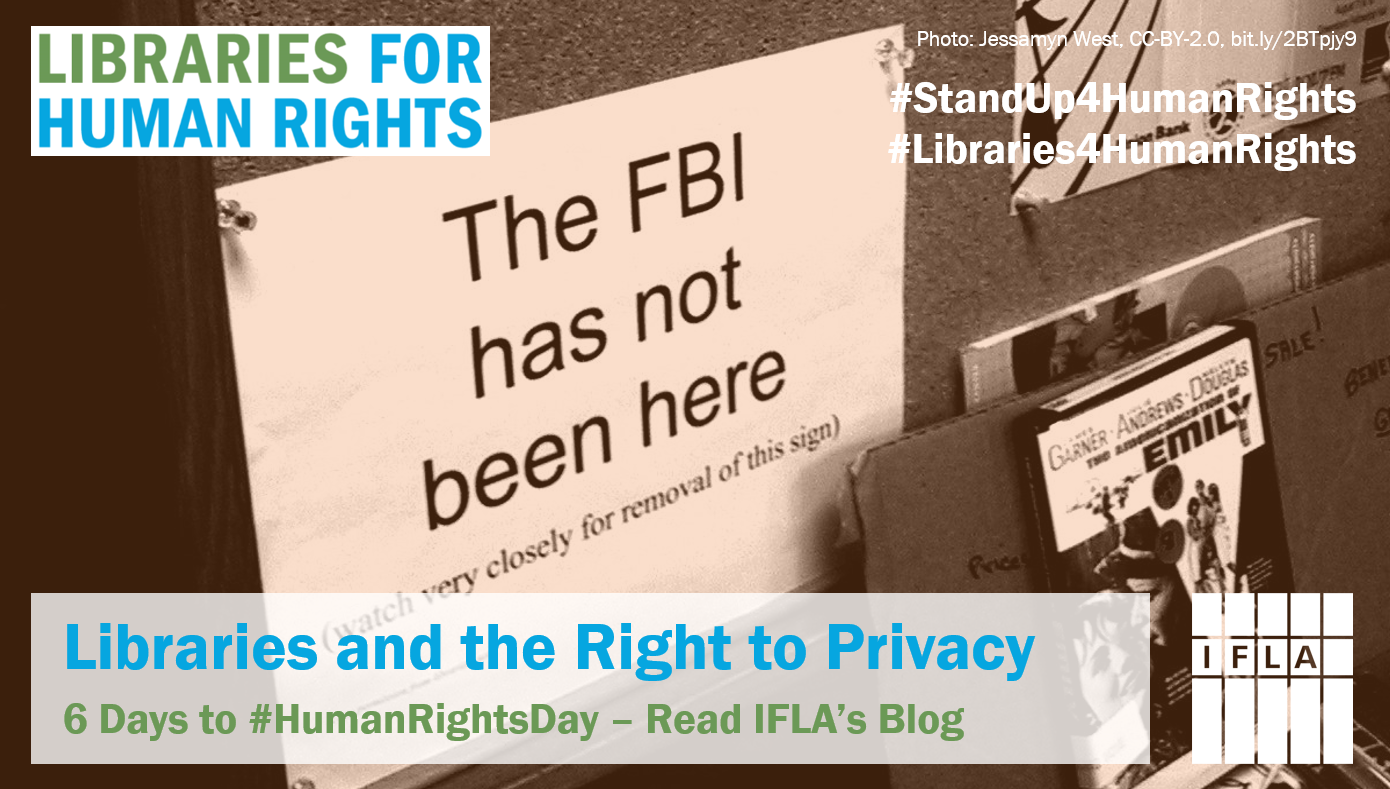

As with all human rights, constant work is needed to support their realisation, and ensure that people are not missing out. It is perhaps not by accident that within a year of the agreement of the Universal Declaration, the UNESCO Public Library Manifesto was also signed, stressing the importance of everyone having access to a place where they could learn and grow, without discrimination. Libraries have, arguably, become symbols of a societal commitment to freedom of access to information.

But what about their role around free speech? The original Public Library Manifesto argues that libraries ‘should not tell people what to think about, but […] should help them decide what to think about’.

Yet this element of libraries’ work is perhaps less known, and indeed can get lost behind the stereotype of libraries as quiet places, more focused on consumption, not creation, of knowledge and ideas.

This blog will look at two ways in which libraries are involved in linking together the two elements of Article 19, and indeed can be as strong a force in promoting free expression as they are in promoting access to information.

Two Sides of the Same Coin?

Libraries have a strong vested interest in free expression. Without the production of varied new books, articles and other materials, librarians will find it harder to develop diverse collections responding to the needs and interest of their communities.

For example, in order to serve users who belong to marginalised groups or communities, libraries may well require books that talk about their experience, and their concerns. Yet if writers are not allowed to take these perspectives, or approach these subjects, the supply of books dries up, and libraries cannot fulfill their mission.

In turn, by giving access, libraries can ensure that these works are read, and so help their authors reach more people than otherwise would be possible.

Initiatives such as Banned Books Week bring these two elements of Article 19 together by highlighting the impact of censorship both on the ability of library users to choose what they want to read, and the ability of writers to have their voices heard.

Towards Convergence

Seeing free expression and access to information as two sides of the same coin nonetheless implies a binary view of the world – that there are some people who produce, and some who consume knowledge.

While this may have been true when publishing a book or communicating views required expensive equipment and infrastructure, this is no longer the case. It has never been easier or cheaper to produce an article or book, or record a new work, and then share it with the world.

Indeed, there is a strong argument that the most effective form of access to information is when someone is able not only to find, understand and use information, but also create and share it.

Through the production of new information, not only do individuals fully realise the potential of the information they have, but others benefit from the results. The results of these new possibilities are already visible through the huge variety of content and ideas available on the internet.

Here too, libraries have a role.

Many have long encouraged activities such as creative writing, but now are branching into maker spaces and other means of promoting creativity. Supporting the application of tools such as text and data mining on library materials allows for new research. And through Wikipedia editathons and community archiving, they are helping under-represented groups become creators themselves.

The summary of the first phase of IFLA’s Global Vision sets out that libraries should be champions of intellectual freedom. This implies breaking away from stereotypes, from the idea that libraries are only really about access. But it is a necessary break, and an opportunity to realise fully the potential of our institutions as drivers of development.