Providing meaningful access to information is not just about creating the physical possibility to get hold of information, but also about delivering the skills necessary to use it.

With growing recognition of the importance of competencies in order to allow people to make the most of an information-rich – or even information-saturated world – the role of libraries not just as a repository, but rather as a skills-provider at the heart of the education infrastructure has become clear.

It is not just libraires who recognise this – organisations in the lifelong-learning sector (here and here), as well as governments working to promote digital skills in general – have underlined the value of involving our institutions.

As such, it can be helpful to follow the wider policy discussion about lifelong-learning and skills, in order to be able to take available opportunities to place libraires at the heart of the development of strategies in the field.

A good starting point for this is the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Skills Outlook (including a free-to-read version), which appears once every two years. This highlights key themes that policy-makers will need to consider in taking decisions, drawing on internationally comparable data, as well as offering national profiles.

This blog highlights some of the central messages of this work that can be relevant for libraries in their planning and advocacy.

An essential response to a changing world, in the long- and short-term

A first key point made by the report is the importance of skills in general. Evolutions in the economy, often driven in turn by technological change, have meant not only that whole categories of job have emerged and declined, but that even to carry out a single job, the skills required change over time.

This need for regular retraining and lifelong-learning was already growing in the years before COVID, with existing skills become obsolescent quicker than ever.

However, the pandemic has only accelerated this trend, hitting some sectors hard while others have remained stable or even grown. Many people will find themselves needing to gain the skills needed to take on new jobs.

Alongside other ‘transversal skills’ (including things like communication, problem-solving and creativity), it seems clear that digital literacy skills will be crucial to this. As the report points out, the ability to use digital tools to work remotely has been essential for work to continue in many sectors, as well of course as to communicate with others and access information.

Digital literacy has, also, been key for access to skills. There are many learning opportunities online, but as the report notes, to benefit from these a potential learner needs already to feel confident.

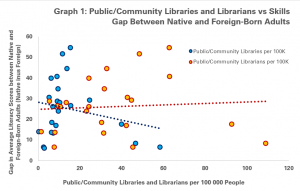

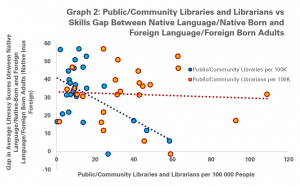

Skills – and possibilities to gain skills – are unequally distributed

Worryingly, despite the importance of skills in allowing people to respond to change, some are less active in developing them than others.

A key factor behind this, as highlighted by the report, is level of initial education. Those who have been able to pursue formal education for longer are also then more likely to carry on taking opportunities to learn throughout life. Yet also, investment in early-years skills, such as literacy, also make a big difference.

Job types also matter – people in skilled work are more likely to receive support from employers to develop further skills, as well as being able to learn from colleagues. Meanwhile, people who are out of work, or in short-term or less skilled work have a higher chance of not benefitting from training.

This gap all too often turns into a gap in attitudes, with some far more positive about learning than others, and to readier to look for and take up opportunities.

On a personal level, this risks seeing people less able to respond to change, and so condemned to low-paid work or unemployment. On the level of societies and economies, it risks creating divides, as well as wasting potential.

Designing a response, with libraries

The OECD draws on the experience of those countries which are doing better in trying to close this divide in order to offer lessons for others, while acknowledging that no-one has yet found the perfect solution.

One key focus, it suggests, is to work on developing the core skills necessary for people to take advantage of wider learning opportunities.

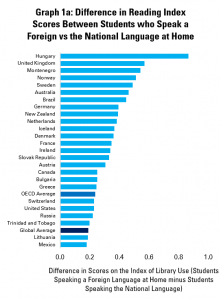

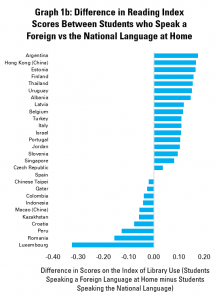

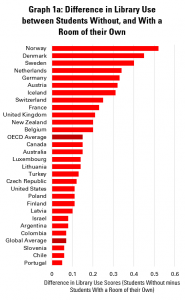

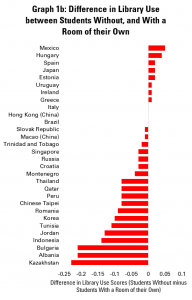

A major component of this is of course reading. The report underlines correlation between levels of literacy and levels of uptake of training in general. In turn, enjoyment of reading correlates strongly with literacy.

This is, of course, an area of key library strength. Use of libraries and enjoyment of reading tends to correlate, as do numbers of school libraires and enjoyment of reading. Librarians have a strong background in building a love of books by exposing young people to a wide variety of materials than can grab their attention and help them to become independent, confident readers.

A second component is around developing digital literacy. As highlighted above, digital skills are not only important for taking on many jobs today, but they can also make the difference between accessing and not accessing learning opportunities.

Again, this is a library area of strength, with many public and other libraires providing the equipment, skills and setting needed for everyone to get the best out of the internet. Many governments already recognise this role of libraries in digital skills strategies.

A third is about ensuring that people find out about the possibilities open to them. Individuals are too often not aware of the opportunities that exist, or confused by the choice. While effective career counselling can be vital within schools, adults too can benefit from help and guidance in choosing courses to follow.

A final one is to provide a wide range of types of learning, in different formats, which can suit the needs and situation of different learners – ‘life-wide learning’ (as opposed to ‘lifelong learning’). Longer, more formal courses may not work for everyone.

To deliver on this, a variety of settings and types of programming can help ensure that everyone finds something that works for them, in particular outside of the workplace.

As a result, based on the report, we can define the following advocacy points for libraries, based on the points made in the OECD’s Skills Outlook:

- Governments must not neglect basic literacy. In particular, they can gain from supporting interventions that build enjoyment of reading – something that represents a traditional strength of libraries, and should be integrated into policies in the field.

- Governments need to invest in digital literacy and inclusion, as a precondition for developing the skills, and taking on the jobs, of the future. Libraries have a recognised role in digital skills provision and should be at the heart of strategies on the subject.

- Governments should ensure easy access to information about learning opportunities for all members of the community, regardless of age or work status. Libraries represent an ideal placer to do this, as well as a portal towards specialised skills providers.

- Governments need to acknowledge the role of a variety of institutions in delivering skills. In addition to formal education institutions, libraries also offer important complementary provision (not just literacy and digital skills, but also a variety of programmes targeted at different competences and groups, in an environment that often puts learners at ease.