The closure of schools as part of the response to COVID-19 has had major consequences that have not only been felt in the short-term, but that may continue to be felt well into the future.

Teachers have been obliged to change their way of working dramatically at short notice, going from in-person teaching to online. This has forced a rapid learning process which, however successful, has still left the frustration of not being able to interact with and support students in person.

In turn, while many are still able to continue to work from home, teachers have again been among the first to return to their jobs.

Of course, librarians in all library types involved in promoting education and learning, will share these feelings. Stories of shifting activities online, adapting and innovating using digital technologies, and overcoming challenges are common to both professions.

But the shared experiences are not just limited, in abstract terms, to the type of work being done. Collaborative working is also happening in reality, on the ground, with librarians working hard to support and complement the work of teachers, even in difficult times.

To mark World Teachers Day 2020, this blog highlights just some of the examples we have seen of support being given:

From Physical to Digital Materials: clearly one key form of support provided by librarians to teachers was access to materials both to support lessons, and to encourage wider reading (itself a key driver of literacy skills).

Even with libraries physically closed, this role has continued, for example at the Marisa Escola Social Santa Monica in Brazil, where the library engaged closely with teachers in their lesson planning to identify and provide access to appropriate materials. With so many materials available on the internet, help in finding the right ones has been strongly appreciated.

Similarly, the Portuguese School Libraries Network created consultation hours where teachers could approach school librarians in order to identify available materials for lessons. Meanwhile in Massachusetts, United States, school librarians joined teacher Zoom meetings in order to understand needs, as well as proactively reaching out to set out how they could help.

Other libraries have stepped up, with the National Library of Spain for example expanding and promoting its offer of curated materials to support education.

Continued Support for Literacy: another key way in which libraries support teachers is by helping develop the wider literacy skills that ensure that students can engage more effectively with other subjects on the curriculum. School and public libraries in Malaysia, for example, have used social media and other tools to advance the country’s wider programme for reading promotion, eNILAM.

School libraries have worked to make the most both of physical and digital collections, even under pandemic conditions. For example, Roosevelt Elementary School in Lakewood, OH, United States set up a ‘book-grab’ service based on a virtual school library, looking to give children as strong a sense of continuity as possible, alongside activities such as ‘battles of the books’.

Children have also, of course, benefitted from work in public libraries to maximise access to collections, develop online storytimes, and in particular, to deliver digital library cards thanks to agreements between schools and libraries.

Wider Skills Provision: libraries have also been working hard to realise their potential in providing after-school or other extra-curricular learning opportunities that complement what children learn in school. For example, in Portugal, libraries have coordinated with schools in order to run programmes that start soon after school hours, in order to keep children engaged and learning.

Arlington libraries, VA, USA have encouraged children to create ’quaranzines’ in order to express their creativity and share their experiences, while the National Library of Jamaica has developed programming focused on helping students towards their exams.

While activities such as summer reading challenges (in the northern hemisphere) have often not been possible in person, this has not stopped libraries running programmes online, with the National Library of France running events every week in coordination with the Ministries of Culture and Education. Meanwhile, in the US, libraries are finding new ways to run maker-spaces, teach STEM skills or promote information literacy and critical thinking.

These examples of course only scratch the surface. As such, they give just a tiny view of all that libraries can do – and are doing – to help teachers during extraordinary times. Across these, the value of close cooperation between teachers and librarians appears clear, both in order to ensure that teachers understand what libraries can offer, and librarians understand what teachers need.

As the world looks to imagine a future post-COVID, we can hope that a key part of this will be enhanced cooperation with libraries. As we have seen, when cooperation succeeds, students stand to benefit, reducing the risk of long-term negative impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic.

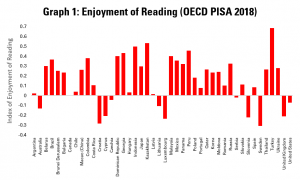

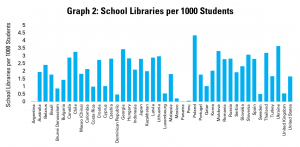

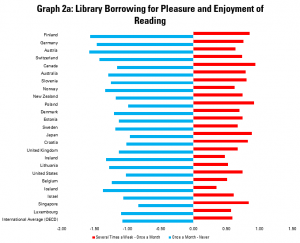

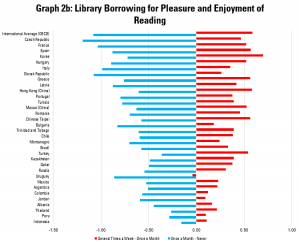

These graphs indicate levels of enjoyment of reading amongst 15-year olds who borrow books only once a month, compared to those who do so never, and those who do so several times a week.

These graphs indicate levels of enjoyment of reading amongst 15-year olds who borrow books only once a month, compared to those who do so never, and those who do so several times a week.

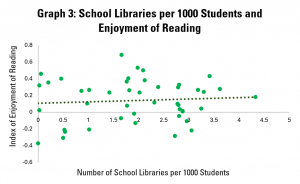

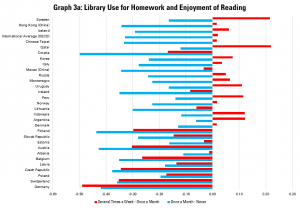

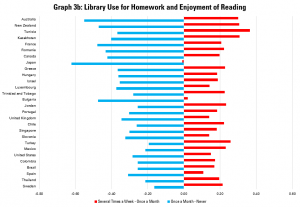

Graphs 3a and 3b look at the links between levels of enjoyment of reading and how often students use the library to carry out homework.

Graphs 3a and 3b look at the links between levels of enjoyment of reading and how often students use the library to carry out homework.

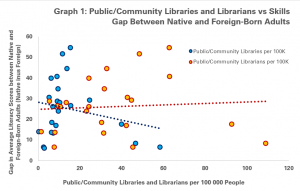

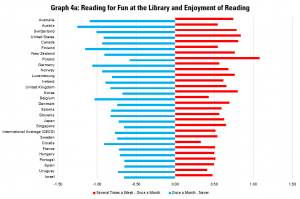

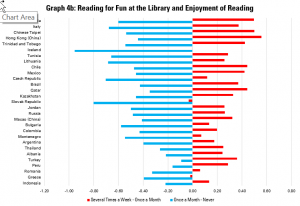

Finally, graphs 4a and 4b look at the links between enjoyment of reading and using the library to read for fun. Again, it is expected that more regular reading for fun at the library is linked to greater enjoyment of reading in general.

Finally, graphs 4a and 4b look at the links between enjoyment of reading and using the library to read for fun. Again, it is expected that more regular reading for fun at the library is linked to greater enjoyment of reading in general.