Information has long been political – who has it, who should have it, and how can it be used to shape decision-making. However, it is only relatively recently that this has been recognised.

On the philosophical side of things, much comes from the work of thinkers such as Michel Foucault, who explained the power that comes from organising information in specific ways (‘knowledge is power’). On the more practical side, the emergence of the internet has given a practical focus to broader reflections on how information is created and shared.

It therefore makes sense to think about the politics of information – the discussions and disagreements that take place around key issues. These questions are particularly key for libraries, as central stakeholders in how information is accessed, shared and governed.

2018 has seen a number of key debates come into focus, with further developments expected in 2019. These relate to whether information should be privatised or made publicly available, where privacy should triumph over access, and where free speech should give way to public order concerns.

This blog will offer a short introduction to each question, and relevant examples of legal and policy discussions which will shape information politics in the coming year.

Privatisation vs Public Availability of Knowledge

Knowledge – at least in the form of books or other documents – was long subject to constraints both on producers and users. These helped avoid widespread copying, but at the same time allowed users some flexibility in what they did with the written knowledge they held.

The expense of owning a printing press meant that the number of people who could publish was limited (although of course not enough to prevent calls for copyright to be invented in 1709). At the same time, once a book or newspaper had been sold, it was easy enough to share it with others or use it for research or other purposes.

Therefore, while the concept of copyright was intended to give the writings contained in books and other documents the same status as physical objects (in terms of the possibility of owning them), it was only ever an imperfect solution.

Digital technologies have weakened these constraints. It is far easier to publish (or copy) and share works than ever before, but also to place limits (through a mix of legal and technological means) on their uses. In other words, it has never been easier to provide universal access to knowledge, but at the same time, it is also simpler to make the knowledge contained in a book or other document private, with all access and use subject to licences.

These new possibilities have created a gap in legal provisions in many countries, given that there had, previously, been no cause to make rules. With this has come a sense that laws also need to be updated, rather than leaving things up to the market or the courts. This is the underlying reason for the ongoing European Union copyright reform, but also elsewhere.

Specific questions raised in this reform, as elsewhere, include whether people involved in teaching should be able to use materials to which they have access, whether researchers and others should be allowed to carry out text and data mining, and whether libraries should be allowed to take preservation copies.

There are also questions about whether the platforms which allow users to share materials should place the protection of intellectual property above the right of their users to free expression.

2019 is likely to see some sort of conclusion to discussions on these subjects in the European Union, South Africa and Nigeria, as well as key steps forwards in Canada, Singapore, and Australia.

Protecting Privacy vs Giving Access

The idea of ‘ownership’ of information is not only associated with intellectual property rights. Increasingly, it also comes up when we talk about personal information – anything that says anything about a person.

Once again, the idea that people have an interest in information about them is not new – there have long been laws on libel which allow individuals to act against writings that are unfair or defamatory. Rulers have also been prolific users of laws against sedition or lèse-majesté. However, such provisions have tended to be limited to the wealthy and powerful.

Here too, digital technologies have changed things by allowing for a much greater potential to collect and use information about people, be it for advertising, security or other purposes. They have also – for example through search engines – made it much easier for ordinary people to access information that might otherwise have been forgotten or too difficult to find.

With this, the idea of a right over information about you has emerged in a number of privacy and data protection laws around the world. The primary focus tends to be on data gathered by companies, with justifications running from a desire to understand advertising choices to enabling customers to shop around between service providers.

In parallel, security concerns have tended to see greater powers given to governments in the types of data they can collect and use, as well as limitations on the transparency obligations they face.

2018 saw the entry into force of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, and similar rules emerge in a number of US States and Latin American countries. There have also been new security rules applied giving governments new powers to gather data on suspected terrorists (as well as many others).

2019 may well see more similar efforts, as well as new efforts to take advantage of new powers over personal information.

Protecting Free Speech vs Tackling ‘Dangerous’ Content

A key way in which the political value of information has long been recognised is through the efforts made to control free expression. Ideas and writings deemed to be dangerous to political, economic or social goals, for example through calling for insurrection, infringement of copyright, or simply because it is criminal, have long been the subject of attention by governments.

It is true that the right to free speech is a crucial one, but it is not absolute. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights notes that all rights can potentially be limited when this is necessary to fulfil the rights of others. As regards the right to equality, there is explicit mention of the importance of combatting incitement to discrimination.

More recently, the way the internet has developed has both made it easier for people to share and spread ideas (dangerous or otherwise). It has also involved relatively well defined actors and channels – search engines, social media platforms, internet service providers – with key powers over what is shared. Through their own actions – or actions they are obliged to take – there is a possibility to exert much greater control over what can be said and shared than when someone opens their mouth.

We come across this debate in discussions around concepts like ‘fake news’, terrorist content, hate speech, criminal content, and to some extent copyright infringement. In each situation, there is content that is clearly illegal and clearly legal. But there are also often grey areas, where judgement and nuance may be needed.

The problem is that the solution often proposed for identifying and blocking such content – automatic filtering, brings its own challenges. There are issues that go from the practical (are they good enough?), to the political (without incentives to protect free speech, do they risk ‘accidentally’ blocking legal content?), and human rights-related (should rights be given and taken away by a machine?).

At the same time, human moderation is expensive (in particular if done properly, by people with knowledge of relevant cultures), and can cause serious psychological damage to the people doing it. The costs are likely too high for smaller actors.

Clearly, this is a particularly difficult problem in information politics, not helped by cross-over with other areas of politics. This can make it hard to promote proportionate or nuanced approaches.

There is legislation in a number of jurisdictions which seeks to crack down on terrorist content and copyright infringement through (explicitly or otherwise) automatic filtering. Some have sought to ban ‘fake news’ (a highly dubious step), and others have put pressure on internet platforms to do the same, creating incentives to take an ever tougher line on content. With public pressure growing, major internet companies seem set to implement ever more conservative approaches in order to avoid blame.

What Implications for Libraries?

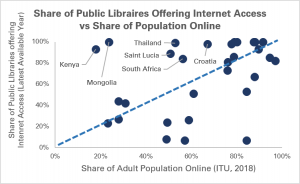

As highlighted at the beginning, libraries are key actors in information politics. They are central – both practically and symbolically – to the idea that everyone should have meaningful access to information.

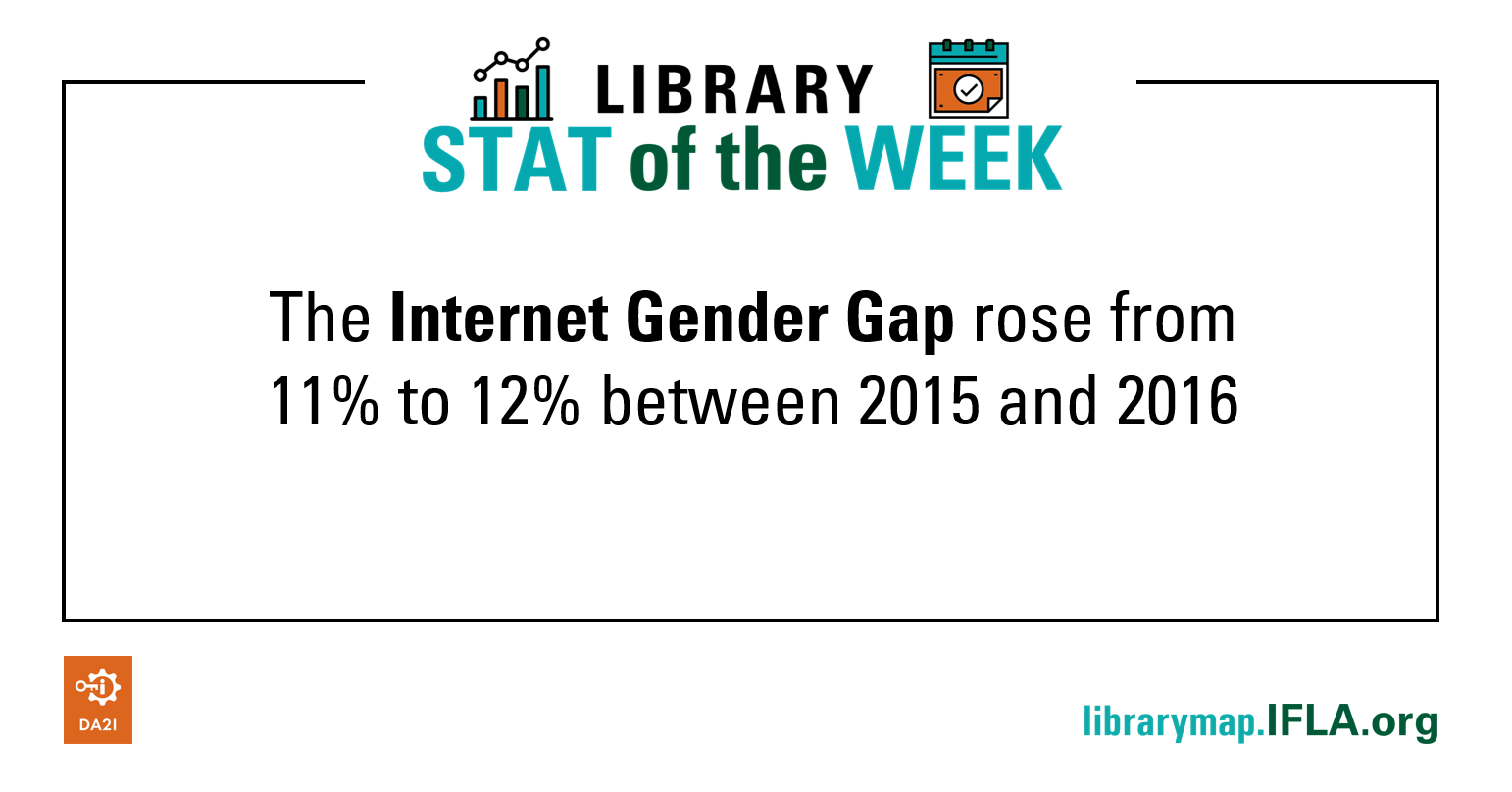

A first priority is to defend this core idea. Too many are still offline, too many lack formal education or the possibility to learn throughout life, too many cannot find the information they need to live healthily, find work or start businesses, or to engage in public life.

Libraries are also unique, as public, welcoming institutions, with a clear social interest goal, rather than a focus on profit. Nonetheless, this status does not spare them from the effects of decisions taken in relation to the three major debates set out above.

They clearly depend on limitations on the privatisation of knowledge in order to do their jobs, but need a system that allows writers, researchers and others to keep on producing. They need to protect privacy (key to giving users the sense that they can seek and share information freely), but must also resist sweeping restrictions on what materials they can collect, hold and give access to.

And while they understand the need to act against dangerous speech, they know from long experience that managing information is complicated and requires skilled judgements based on expertise and values – something that a machine cannot replicate.

While it may not always be popular – or easy to explain – libraries will need to set out and defend the importance of a balanced approach, one that allows for meaningful access to information for all, not just in 2019 but long into the future.

This blog is based on a presentation initially given at the Eurolib conference in Brussels on 12 November 2018.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) – systems able to collect and analyze structured or unstructured data and make decisions based on that information to achieve a defined goal

Artificial Intelligence (AI) – systems able to collect and analyze structured or unstructured data and make decisions based on that information to achieve a defined goal