The rise of eBooks has led to some significant changes in the world of publishing. While they are clearly a long way from replacing their physical equivalents, eBooks do now enjoy a significant share of the market, and have allowed a lot of independent and self-published authors to emerge.

They have also brought questions about what it means to ‘own’ something to the world of books and reading.

Because while buying a physical book represented a pretty definitive transfer of ownership – the buyer could then read, scribble in the margins, share with a friend, give it away or resell it – it’s different with eBooks.

Libraries are of course also affected by this restriction on ownership. Not only are they not always allowed to buy eBooks (not a challenge when a library would stock up at a local bookshop or other vendor), but then their ability to lend books, and on what terms is different.

From Anecdote to Hard Evidence

This situation has led to a lot of frustration, but until recently, only limited and anecdotal evidence of what was going on. However now, thanks to an Australian team led by Professor Rebecca Giblin and drawing on a team of lawyers, data scientists and others, there is an impressive body of data about what eLending looks like for libraries. This is available at http://elendingproject.org/.

Professor Giblin’s work is in fact based on three smaller studies: 1) one looking across 546 culturally significant books across different platforms in Australia, 2) one looking at the same set of books on one platform across Australia, NZ, US, Canada and the UK, and 3) one looking across almost 100 000 eBooks available in at least one of the five countries, through one platform.

Throughout this work, the aim was to look at questions around availability (what eBooks could libraries buy), and accessibility (on what terms – cost/licences – they could buy them).

This blog summarises the information, and you can watch the presentation of the information at last year’s World Library and Information Congress.

Buy Me If You Can?

A first key conclusion is that the availability of eBooks is highly variable. In Australia, of the 546 culturally significant books, individual aggregators only had 62-71% on offer. Looking across the five countries, the figure went from 71% of these key books being available in the US, but only 59% in the UK.

Taking the larger study, 12% of books available in other countries were not in the US or Canada, but this figure rose to 23% in the case of the UK. There appears to be a link between price and availability of books, at least in Australia, NZ and the UK. Hachette has particularly diverse policies – around 90% of their electronic catalogue was available in the US/Canada, but only 3-4% (16 books) in the UK and Australia.

Responding to Demand?

Despite original suspicions that older books (the ‘backlist’) may not be available to libraries, the data seems to show that availability is in fact pretty good, including books from the first half of the 20th century. However, older books are not necessarily licensed in different ways to newer ones, despite the fact that they normally are subject to lower demand and usage.

For libraries, time-limited licences are highly unattractive for books which are valuable, but may not be lent out so frequently. However, they are still frequently used for such older books. Moreover, there is no evidence that prices are any lower either, making back-list books less interesting for libraries. Moreover, in 97% of cases, there is zero choice of licence for libraries, reducing choice.

The Bigger, the Tougher?

A key question at the IFLA level is to ensure that library users enjoy the best possible access to works. This is difficult when licensing and pricing practices vary, disadvantaging users in one country compared to those elsewhere.

Interestingly, this question of variation seems to almost entirely focused on the big five publishers. Looking only at books published by the same publisher in the five jurisdictions, 34% of titles from the ‘big five’ were subject to different licences in different jurisdictions, compared to 0.1% for other publishers.

The same goes for prices – these varied by 20% or more in almost half of cases for the big give, whereas other publishers barely varied at all, even on identical licences. Big five publishers are also more likely to use metered licensing (in particular in the UK), while others use one-copy-one-user in the vast majority of cases.

A Lack of Transparency

Finally, based on the Australian data, it became clear that platforms are not always getting the same deal. They are also unable to compete on price.

In Australia, 41% of titles were subject to different licensing terms from aggregator to aggregator, with serious differences in half of these. Prices varied also, although there was strong secrecy about how these were formed.

Implications

The findings offer an important opportunity to understand how libraries and their users are experiencing eLending. It brings welcome transparency to a market which has tended to be seen as fluid and evolving.

Clearly it doesn’t resolve all questions – for example the market impact of eLending (there is no clear evidence either way, although recent evidence from the promotion of one particular book suggests the consequences can be very positive). But it does highlight questions that deserve answers. Crucially, it implies that there are questions about how the market is working now, and raises the question of whether action should be taken.

While eBooks have offered valuable flexibility for readers (and authors), the same flexibility appears not always to benefit and enable libraries to carry out their missions. eBooks provide a strong example of the risks around the shift from physical ownership to digital licensed access.

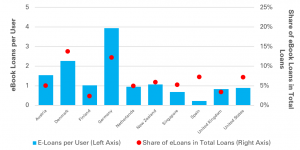

In both Spain and the United States, it’s 1 in 14, and New Zealand 1 in 17. Meanwhile, in all of Singapore, Australia and the Netherlands, it’s around 1 in 20 (or 5% of the total).

In both Spain and the United States, it’s 1 in 14, and New Zealand 1 in 17. Meanwhile, in all of Singapore, Australia and the Netherlands, it’s around 1 in 20 (or 5% of the total).