COVID-19 has placed significant strain on individuals and societies.

The economic damage has been clear, with businesses forced to close, and increased unemployment. While the most immediate impacts have been felt in the private sector, the public sector too is likely to see cuts as governments deal with lower revenues and debts to pay back.

This has inevitable social consequences, coming on top of the trauma of the loss of life, and the regret that many will feel at not being able to socialise and interact with others as they did before the pandemic.

These impacts are not felt equally of course. While many have been lucky to be able to move much of their lives online, this has not been the case for all by a long way.

At the level of individuals, there is often uncertainty about the future, as well as a serious risk of falling behind those who have been more fortunate.

Connected to this, societies as a whole are weakened when inequalities grow, both in terms of social cohesion amongst their members, and their overall potential to produce and innovate.

The job of government is to prevent this from happening, providing the context and support that individuals and societies need in order to recover. They need to act to minimise or avoid long-term scarring from the pandemic, while creating the opportunities for renewal and positive change.

Libraries can be at the heart of this response. This blog sets out five key challenges individuals and societies will face – or are already facing – as a result of COVID-19, and what our institutions can do to help.

Catching up with School: schools and teachers around the world have made a huge effort, in a very short period of time, to redesign teaching for an online environment. This is likely to have made a real difference for many learners.

Nonetheless, those who do not have access to the internet, or who do not have the hardware or space at home to learn effectively, have been at risk of falling behind their luckier peers, as the United Nations itself has underlined. For them, the period of the pandemic risks becoming a lost term – or even year – dragging them further behind.

Public and school libraries have long had a role in supporting teachers by encouraging and supporting reading and research outside of the classroom, for example in the United States. This role is more central than ever now, with libraries stepping up to deliver online after-school programming, designing activities and challenges, and providing tailored materials and support to help learners most in need!

Help to Access Employment Support: with unemployment already rising, millions of people are going to be looking for work in the coming months. The support that governments and other agencies can provide – benefits and job-search support – will be essential for many, especially those who start with fewer skills or resources to start with.

Yet again, too many people do not have the possibility to get online, or the devices necessary to prepare a CV, prepare a business plan, or apply for benefits or other forms of support. Furthermore, for many, pride or other factors may keep them away from job centres.

Libraries are already helping here, from printing out and delivering applications for government benefits, to providing access to resources for prospective entrepreneurs, or training to help jobseekers gain the skills they need, such as in Livadia, Greece.

Smarter and Fairer Innovation and Decision-Making: the COVID-19 pandemic has proved a major test of the ability of governments to take decisions, and of scientists and researchers to respond to an urgent priority.

In a few months, we have learnt a lot, leaving societies better prepared to respond to new clusters of cases. At the same time, we have also become aware of the many questions that remain open. To respond, there have been rapid advances in ensuring open access to relevant materials, as well as developing platforms for sharing information and carrying out collaborative research.

One key conclusion from this is the need for ready access to information – the speciality of libraries. From evidence reviews in support of government decision-making – as highlighted in the webinar organised by IFLA’s Special Interest Group on Evidence for Global and Disaster Health – to infrastructures for data on COVID-19, libraries have been essential to providing the best possible chances of finding a way out of the crisis.

Rediscovering a Sense of Community: less tangible, but no less important for wellbeing and social cohesion is the possibility for people to feel connected to each other. In societies where living alone is more and more common, especially among older people, loneliness and isolation have risked growing significantly.

While people have shown real resilience in the face of difficulty, it is clear that many miss opportunities to enjoy common experiences.

Again, libraries provide a solution. At an individual level, there are great examples of librarians making sure to schedule calls with regular users, especially those most at risk of finding themselves alone, such as Auckland, New Zealand. The re-opening of buildings should help to provide additional support.

Meanwhile, local libraries are organising activities online – and increasingly in person, where this is safe – realising their potential as often the most accessible cultural infrastructure for their communities. This work is complemented by the efforts of national and major research libraries to provide access to their collections and organising engaging exhibitions.

A Chance to Take a Break: linked to the above, the fact of being obliged to stay at home has not meant that people have had any less need to step back and take time for themselves. Especially with travel impossible or limited, people need a means to escape from the uncertainty and worry that the pandemic has brought.

While of course the key priority has been to ensure that people receive healthcare when they are ill, as well as the food and money needed to survive physically, we cannot underestimate the importance of culture as a source of wellbeing and respite, as the World Health Organisation has noted.

Once again, libraries provide an accessible and equitable means of doing this. There have been major increases in people signing up for, and using, library digital offerings, both from national and public libraries.

While copyright and the licencing terms offered by rightholders have sometimes limited scope for action, libraries globally have innovated and found ways to provide their communities with cultural experiences, in ways that work for them.

There are of course many other ways in which libraries support communities. IFLA’s work around the Sustainable Development Goals, for example, underlines the variety of ways in which our institutions can make a difference.

Nonetheless, in advocating for libraries now – at a time when many will face challenges to their funding – it is valuable to focus on the most pressing issues that governments themselves need to resolve.

By applying examples and lessons from your own context to show how libraries can provide solutions, you can strengthen the case you make for ongoing investment in library and information services. For example, Libraries Connected in England provides a great example of structuring advocacy around these sorts of challenges.

Good luck!

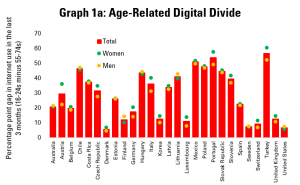

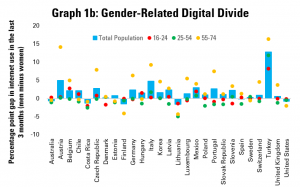

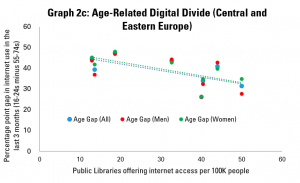

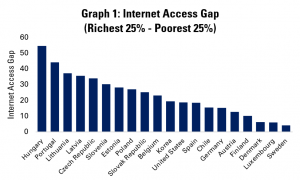

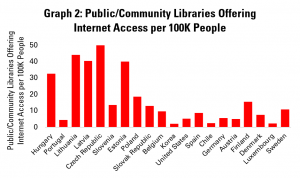

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens.

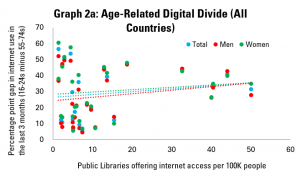

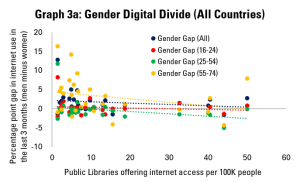

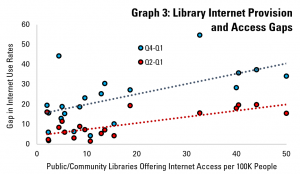

Graph 2 displays (with the same order of countries as before) the number of public and community libraries offering public internet access per 100 000 people. The Czech Republic scores highest here, with just over 50 such libraries for every 100 000 people – that’s one for every 20 000 citizens. We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access.

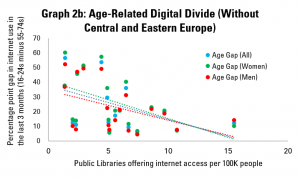

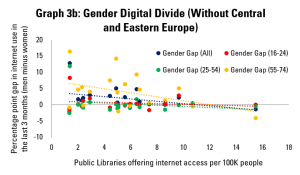

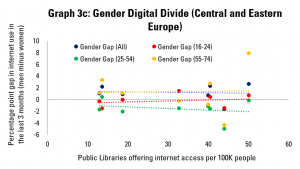

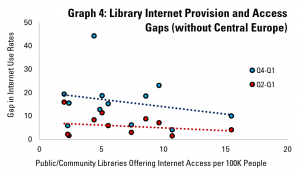

We can cross these figures in Graph 3, which aims to look at the relationship between income-related internet access gaps and the availability of libraries offering access. As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.

As an additional step, Graph 4 carries out the same analysis, but not including countries from the former Eastern bloc.